Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 13/164/06. The contractual start date was in December 2015. The final report began editorial review in December 2019 and was accepted for publication in September 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Kidger et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Young people’s mental health

Mental disorders among 11- to 15-year-olds in the UK have risen in recent years, particularly among girls experiencing emotional disorders, with 13.6% among this age group identified as having one or more disorders. 1 Cohort studies indicate that levels of distress and difficulty in the early teenage years are increasing,2 with 25.7% of teenagers aged 14–15 years, and as many as 37.4% of girls in this age group, reporting high levels of psychological distress. 3 There is also evidence that self-harm is increasing among young people in the early to mid-teenage years, particularly among girls. 2,4 Intervening early to support young people’s mental health is important to avoid the development of more serious and long-term problems,5 as approximately half of all adult mental disorders begin during adolescence. 6

Given that only 25% of children and young people with a diagnosable condition are able to access Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS) support,7 it is vital that non-specialist settings, including schools, where most children and young people spend a great deal of their time, are equipped to engage in early prevention work and support those at risk of developing a mental health problem. A large number of school-based studies seeking to improve children and young people’s mental health focus on developing individual coping skills or mental health literacy. There is mixed evidence as to the effectiveness of such programmes. A recent systematic literature review8 found some effects on prevention or reduction of anxiety and depression for a short time. However, a recent network meta-analysis9 did not find such positive results and concluded that previously observed effects may be driven by differential control group effects.

As well as attempting to develop young people’s own skills and knowledge regarding mental health maintenance, it is important to consider changes to the school environment to ensure that it is supportive of mental health. Research has shown that teachers are the professionals that teenagers are most likely to talk to about mental health difficulties,10 and also that perceived supportive relationships with school staff can be protective of future depression for students in secondary schools. 11 Conversely, difficult teacher–student relationships among this age group predict mental health problems and future exclusion. 12 Despite the importance of positive relationships with teachers for student mental health, many teachers report a lack of training in how to support students. 13,14 In a questionnaire commissioned by the Department for Education in 2015, 52% of respondents working in schools identified training for staff as an important strategy to support student mental health. 15 The government’s pledge to train one senior lead on mental health in every secondary school in England16 is unlikely to go far enough in terms of strengthening all teachers’ ability to develop supportive relationships with students, and to know how to help those at risk of poor mental health.

Teachers’ mental health

In addition to a lack of training, another barrier to teachers providing appropriate support to students is their own poor mental health and well-being. 17,18 Health and Safety Executive data for Great Britain consistently show teaching professionals to have higher rates of work-related stress, anxiety and depression (recent figures show a rate of 3020 per 100,000 for teaching and education professionals vs. a rate of 1320 per 100,000 for all industries). 19 Causes of these heightened levels of work-related stress and distress have been identified as excessive workload, lack of autonomy, poor salary, perceived lack of status, challenging student behaviour, difficult relationships with colleagues and managers, and pressure to ‘perform’ in a context in which schools are increasingly regulated and judged against an array of externally determined targets. 20–23 These stressors may be exacerbated by a culture in which teachers feel unable or unwilling to ask for help. 3,24 Failure to support teachers experiencing such difficulties may lead to longer-term mental health problems, presenteeism (i.e. going to work when one is mentally or physically ill) and sickness absence or quitting the profession. 25–28 Presenteeism for teachers may result in difficulty managing classroom behaviour effectively and supporting vulnerable students,29,30 both of which may impact on student mental health. 31

Interventions to improve teacher–student relationships

A small number of previous studies have attempted to enhance teachers’ support of students with the aim of improving student outcomes. The INCLUSIVE study32 found that a whole-school approach to strengthening relationships among students and between students and teachers reduced bullying and psychological difficulties among UK secondary school students. The Supporting Teachers and Children in Schools (STARS) trial33 found that the Incredible Years training, which aims to improve school teachers’ classroom management skills and strengthen teacher–student relationships in UK primary schools, led to a short-term (9-month) improvement in student mental health, although this was not sustained. The Saving and Empowering Young Lives in Europe (SEYLE) trial,34 conducted across 10 European countries, compared the impact of three interventions on suicidal ideation and attempts among secondary school students: (1) training school staff to recognise and support at-risk students, (2) delivering a mental health awareness programme to students and (3) screening and referral of at-risk students by professionals. This trial found that only the awareness raising intervention had an impact on suicide ideation and attempts, although the other interventions showed promise, with the confidence intervals (CIs) overlapping across the three. The authors suggested that the smaller effect of the staff training element may have been because poor teacher well-being reduced teachers' ability to support students. 30

Workplace interventions to support mental health

No previous studies have evaluated the impact of improving support for teachers’ own mental health alongside improving their skills in supporting students. A number of reviews have examined the effectiveness of workplace interventions that aim to reduce stress or improve mental health, and report that approaches such as cognitive–behavioural therapy, self-help, exercise and mindfulness interventions have all been found to be effective at reducing workplace depression and other common mental disorders. 35–38 The only systematic review39 that looked at interventions to support teachers’ mental health specifically investigated the impact of organisational-level change. Of the four studies included in this review, one looked at changing teachers’ tasks (e.g. establishing flexible work schedules) and reported a resultant reduction in work stress and small increase in performance. Two studies evaluated coaching support, but found no effects on anxiety, depression or burnout. The final study found that a multicomponent programme, which included performance bonus pay, job promotion opportunities and mentoring, led to reductions in teacher resignations. However, the authors note that the quality of studies was poor.

Social support has been found to be protective for mental health in the workplace. 40 Bricheno et al. ,41 in their review of teacher well-being, identified evidence from questionnaires and case studies that teachers themselves view support from colleagues, senior staff and head teachers as an important factor. Workplace peer support has been identified as helpful because of its contribution towards establishing a supportive culture, its basis in shared experience and understanding of workplace challenges, and its avoidance of the perceived stigma attached to more formal help sources. 42,43 However, the evidence base is limited and has tended to focus on peer education to engender behavioural change (e.g. increasing screening uptake or healthy eating). 44,45 A number of peer support schemes have been set up in occupations requiring emotional labour or that potentially involve traumatic experiences, such as health-care professionals, but these rarely produce published evaluations. One published example of a peer support scheme for health-care workers43 described the following features as important: credibility of peers, immediate availability, voluntary access, confidentiality, emotional first aid (as opposed to therapy) and facilitated access to next level of support. Social support is conceptualised as comprising problem-focused and emotion-focused supportive strategies, both of which have been found to have a positive impact on physical and mental health. 46 A review42 of peer support schemes suggests that they provide a combination of informational, emotional and instrumental support.

Mental health first aid training in the workplace

Mental health first aid (MHFA) training has been delivered in the workplace as one way of improving support. 47 MHFA is an internationally recognised training package that is designed to improve lay people’s knowledge of the signs and symptoms of developing mental disorders, and their confidence in helping those in mental health crisis. 48 Course attendees are taught to follow five steps when approaching another person who requires support: approach the person, assess and assist with any crisis; listen non-judgementally; give support and information; encourage the person to get appropriate professional help; encourage other supports (ALGEE). A number of studies have provided evidence that MHFA training is effective in improving knowledge, confidence in helping others and intention to help others, as well as reducing stigmatising attitudes. 49 MHFA delivered in the workplace has been found to provide a number of benefits: encouraging social support,50 increasing self-reported help-seeking from professionals47,50 and improving the mental health of course participants themselves. 47 Participants generally express very positive attitudes towards the training, reporting gains in knowledge and skills, and improved ability to provide help to those around them by using that learning. 51–53 Despite high participant acceptability, and evidence of improved mental health literacy and intention to help, no study has yet been able to show impact of MHFA training on mental health outcomes. 49 However, a shorter training programme that focused on improving knowledge and communication around mental health when delivered to senior managers in a large fire and rescue service did lead to a decrease in absence rates among the staff whom trainees managed. 54

Mental health first aid training in schools

A version of MHFA, the youth MHFA, has been designed specifically for adults supporting young people, using the same ALGEE model. Although the full version has not been evaluated, a randomised controlled trial (RCT) tested a shortened version delivered to secondary school teachers in Australia. 55 At 6 months’ follow-up, this study reported improvements to teachers’ knowledge and confidence to help students and colleagues, but there were no changes in the actual help that teachers gave to students or in student mental health. However, the intervention did not attempt to improve support for the teachers’ own mental health. We sought to build on this study by addressing teachers’ own support needs, alongside the training in how to support students.

Rationale for the current study

To date, school intervention studies have focused on improving student mental health, with the majority of studies evaluating classroom-based psychological or educational approaches. Very few studies have focused on training teachers to support vulnerable students through their day-to-day interactions, despite the role of teachers in identifying and attending to students’ mental health problems, as demonstrated in the research literature14,56 and recommended in key policy and guidance documents, such as the Department for Education’s Mental Health and Behaviour in Schools. 57 Furthermore, no studies have developed and evaluated an intervention that focuses on teachers’ own mental health, despite evidence that they are a group at risk of poor mental health, and that this is likely to influence the health and attainment of those they teach. We therefore developed an intervention in consultation with teachers and public health specialists working with schools, which addressed these gaps and which we planned to evaluate. The Wellbeing in Secondary Education (WISE) trial was the result of this process.

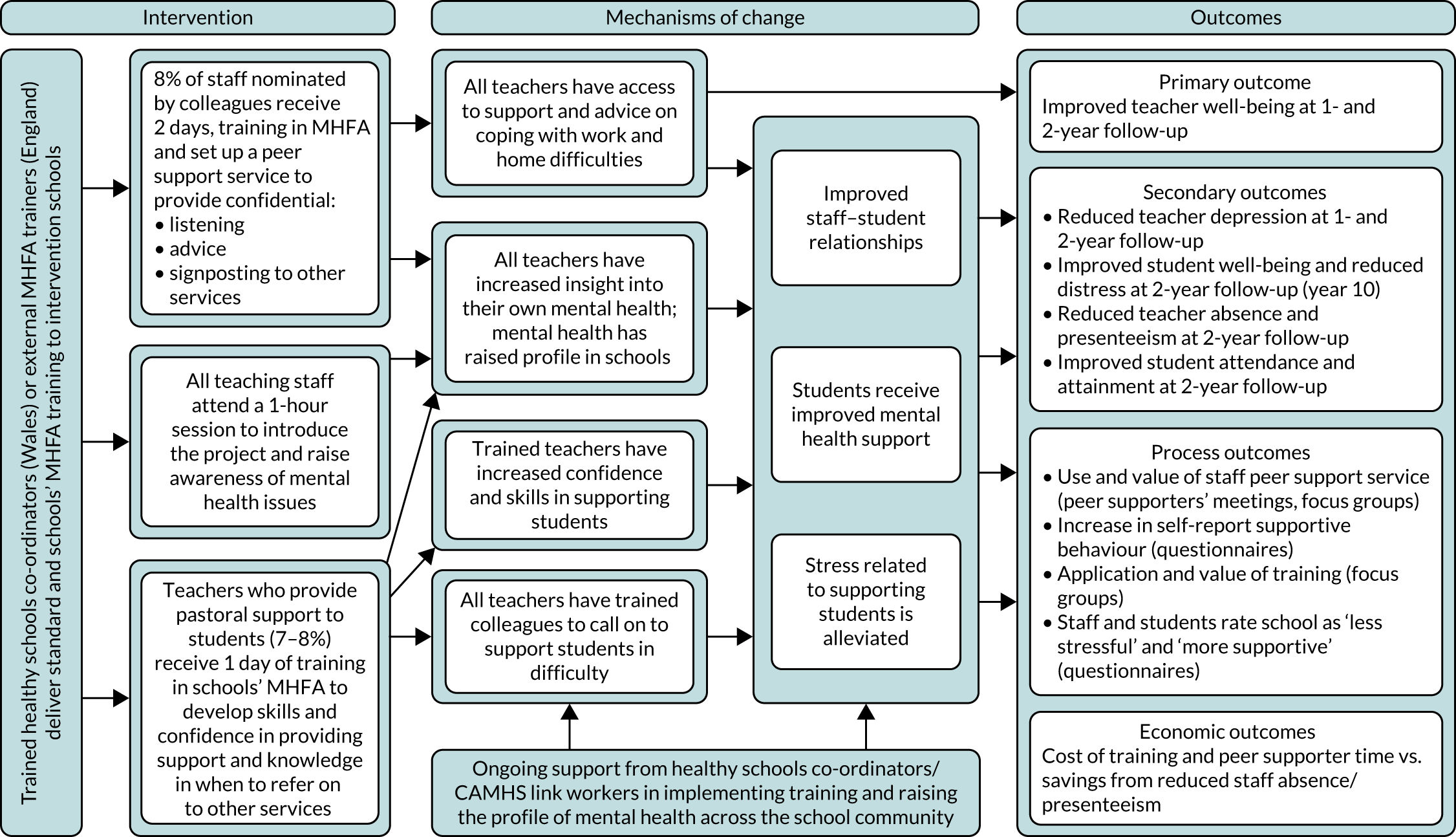

The Wellbeing in Secondary Education feasibility and pilot trial

In line with Medical Research Council guidance for the evaluation of complex interventions,58 we undertook a pilot cluster RCT of the WISE intervention in six secondary schools to explore its feasibility and acceptability. 59 The intervention comprised (1) 2-day standard MHFA training for school staff who went on to set up a peer support service for colleagues and (2) 2-day youth MHFA training for school staff to improve the support they were able to provide to students. The pilot trial also enabled us to test the feasibility of key aspects of the trial design, including the collection of outcome measures and the recruitment and retention of schools, and to develop a logic model as to the likely pathways by which the intervention might have an effect on the outcomes of interest (Figure 1). Key findings from this pilot were as follows:

-

Schools from a range of socioeconomic catchment areas were able to be recruited and retained, although it was necessary to make personal contact with a relevant member of staff to ensure this.

-

Measures of staff and student mental health, and staff presenteeism and absence were able to be collected at baseline and at 12-month follow-up (T1). Data were collected during meetings and not left to individuals to complete in their own time.

-

Staff viewed MHFA training as relevant and useful in terms of knowledge gain and opportunities to reflect on mental health, although a shorter version of the youth MHFA course that focused on practical strategies was suggested.

-

Staff peer supporters were able to be recruited and trained in each school. A mean of at least two interventions per peer supporter over a 2-week period was reported, and the service was viewed positively by staff. However, barriers to using the service were identified, specifically concerns around confidentiality, a preference for talking to pre-established social networks and lack of knowledge about the service.

-

Unlike the earlier study of youth MHFA in schools,55 we found that, at follow-up, students in the intervention schools had higher well-being (WEMWBS score 48.1 vs. 45.8; p = 0.12) and lower levels of mental health difficulties (SDQ total difficulties scale score 11.2 vs. 13.2; p < 0.01) than those in the control schools, once adjusted for baseline measures.

-

Staff who received the MHFA training had improved mental health knowledge and well-being, and lower depression than all other staff, as reported in earlier MHFA studies. 49

-

There were no differences between study arms regarding staff well-being and depression, but we were not powered to detect such changes, nor were we able to examine sustainability as the study only ran for 12 months.

FIGURE 1.

Logic model of the WISE intervention. Reproduced with permission from Kidger et al. 60 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

We concluded that the results regarding feasibility and acceptability of the pilot intervention and evaluation were sufficiently positive to justify a full RCT, powered to measure the effect of the intervention on outcomes, and this is the trial reported here.

The present trial

The WISE trial is a full cluster RCT with integrated process and economic evaluations. 61 It tested the effectiveness of a complex intervention that delivered mental health support for teachers and training in supporting student mental health, with the aim of improving teacher mental health and performance, and subsequently improving student mental health and attainment, through the mechanisms of change identified in the logic model (see Figure 1).

Objectives

The primary objective was to establish if the WISE intervention leads to improved teacher emotional well-being compared with usual practice.

The secondary objective was to answer the following research questions:

-

Does the WISE intervention lead to lower levels of teacher depression, absence and presenteeism, improved student well-being, attendance and attainment, and reduced student mental health difficulties, compared with usual practice?

-

Do any effects of the intervention differ according to the proportion of children receiving free school meals (FSM) (an indicator of the socioeconomic catchment area) and geographical area, or individual-level baseline mental health, sex, ethnicity and FSM?

-

What is the cost of the WISE intervention, and is it justified by improvements to staff and student well-being, and reductions to staff depression and student difficulties?

-

Does the WISE intervention work according to the mechanisms of change hypothesised in the logic model?

-

Is the WISE intervention sustainable?

The intervention: underlying theory

The WISE intervention is informed by social support theory. Social support can offer problem-focused coping strategies and emotion-focused supportive strategies, both of which can have a positive impact on physical and mental health. 46 Based on findings from the pilot trial,59 we hypothesised that peer supporters would provide both emotion-focused support (e.g. by listening non-judgementally) and problem-focused support (e.g. by offering practical suggestions for solutions to work-based difficulties), where appropriate. Perceived availability of social support may be even more important to mental health than actual support,46 and, therefore, the existence of a peer-delivered support service was theorised to have a positive impact on teacher well-being, regardless of actual service utilisation. The programme theory was further informed by an ecological view of school connectedness, which considers the quality of social bonds and interactions within a school to be a characteristic of the whole-school environment or culture. 46 Improvement to teachers’ own mental health and well-being via supportive relationships with peers should lead to more positive teacher–student relationships,61 which is associated with improved student mental health. 12 Therefore, all teachers and students within an intervention school may benefit, regardless of whether or not they themselves directly engage with the intervention. Furthermore, a change made from the pilot to the full intervention was that all teachers were offered a shorter version of mental health training, with the aim of improving interactions between all teachers and students, and enabling all teachers to have a better insight into their own mental health (see Figure 1).

The intervention: description of components

Each intervention school received the following.

Staff peer support service

Following the methods developed and found to be acceptable in the pilot study, all teachers in the intervention schools were invited to nominate colleagues whom they considered would make good peer supporters, via a confidential, anonymous written questionnaire completed at baseline before randomisation. The study population was teaching staff only, because pilot findings showed that this was the group most at risk of poor mental health and because of practical difficulties collecting data from all staff. However, the peer support service was available to all staff, as our patient and public involvement work with school staff identified that a service for teachers only may prove divisive. A list was compiled of the 8% of staff with the most nominations, ensuring a mixture of sex, years of experience and teaching/non-teaching roles. The one exclusion criterion was being a member of the senior leadership team, as pilot findings indicated that staff might not use a support service that included senior leaders because of concerns about performance management. Those on the list were invited to attend the 2-day standard MHFA training and become a staff peer supporter. The MHFA training was generally delivered on school premises (one school had the training at a university, and one school shared the training with another school and attended it there). Schools were offered reimbursement for cover costs for teaching staff. A short session about setting up the peer support service and expectations around this was included in the 2-day training, either delivered by the MHFA trainer (England) or by a study team member (Wales). Following the training, participants were provided with guidelines for setting up the peer support service, developed from patient and public involvement work and pilot study findings (see Report Supplementary Material 1). These guidelines covered confidentiality, advertising the service, support for the peer supporters, communication with the research team and practical considerations, such as where support would be provided. An example policy document including a confidentiality statement drawn up by a pilot school and posters for advertising the service were also provided.

Teacher training in mental health first aid for schools and colleges

At least 8% of all teaching staff who had not received the 2-day peer supporter MHFA training received the 1-day MHFA training for schools and colleges. In our pilot study, findings suggested that teachers who have a support role but who have not received prior mental health training, such as tutors or heads of year, would benefit the most. Schools were, therefore, encouraged to select teachers in such roles to attend, but the ultimate decision about who did attend was made by schools. The aim was to train 8% of the teachers, but schools were free to train up to 16 staff, which is the course maximum. The full 2-day youth MHFA course was made available to staff in our pilot schools, but mainstream teachers were often unable to attend because of its length. Partly in response to these findings, the 1-day MHFA for schools and colleges was developed by MHFA England (London, UK). When possible, this training was delivered during in-service training time to ensure that it was as accessible as possible for teachers. Having completed the training, staff were expected to apply the MHFA learning about how to respond to, and support, a student in distress in their day-to-day interactions with students. The decision to train a different 8% (minimum) of staff in each version of the course meant that 16% of staff were trained in total. A previous study using peer influence to address smoking behaviour found an effect when 16% of students were trained as peer educators. 62

Mental health awareness raising session for all teachers

A 1-hour training session aimed at raising awareness of mental health and to introduce self-help strategies, ways to support other people and the peer support service, was delivered either during in-service training or during staff meeting time. This session was co-produced with a MHFA trainer and drew on core MHFA content, and was delivered by the same team of MHFA trainers that delivered the rest of the training. All teaching staff were invited to attend and schools were also free to invite other non-teaching staff. This element of the intervention was added in response to pilot findings, which suggested that some staff were unaware of the peer support service in their schools, and to strengthen the whole-school nature of the intervention.

Detailed information about the content of the MHFA courses can be seen in Report Supplementary Material 2, where we provide an outline of the observation schedule (see also Chapter 2, Data sources). Further information about MHFA courses can be found on the MHFA England website (URL: www.mhfaengland.org).

The control

The comparison schools continued with usual practice in terms of teacher support and training. The details of what this entailed in practice were examined via an audit as part of the process evaluation (see Chapter 2) and results are reported in Chapter 4. Schools signed a research agreement, stating that they would not access MHFA training during the study.

Implementation strategy

Different models for implementing the training were deployed in England and Wales because of the intervention funders in Wales (Public Health Wales, Cardiff, UK) wishing to make use of existing resources and infrastructure to ensure sustainability if the intervention was found to be effective.

In intervention schools in England, the standard MHFA, the MHFA for schools and colleges, and the 1-hour awareness training was delivered by local independent trainers who had attended MHFA instructor training and received certification. Learning from the pilot indicated that trainers needed to have awareness of the school context and challenges faced by teachers, and two of the three trainers had extensive experience of delivering training to schools. In Wales, seven healthy schools co-ordinators (HSCs) attended a 6-day bespoke MHFA instructor training course, received certification and went on to deliver the three strands of training in the intervention schools. HSCs are employed by local authorities or Public Health Wales and are responsible for monitoring and accrediting schools participating in the Welsh Network of Healthy Schools Scheme. HSCs are experienced in delivering training to schools; however, because they were new to MHFA training, they delivered the training in pairs as per MHFA England protocol.

Originally, the training was intended to be delivered within a single academic term (September–December 2016). However, a small number of schools completed the training in January 2017 because of their staff training schedule, and one school did not receive the 1-day MHFA for schools and colleges training until June 2017 because of a change of leadership creating a delay. The order in which training components were delivered was not prespecified to accommodate the constraints and needs of each school. All intervention schools received all three training components.

For the establishment of the peer support services, peer supporters were asked to meet within 3–4 weeks of completing the standard MHFA training course to plan the logistics of running the service, and to develop a confidentiality policy and advertising strategy.

Summary of the remaining document

In the following chapter, we outline the methods used for the main statistical analysis, the economic evaluation and the process evaluation. In Chapter 3 we present the main outcomes and economic evaluation findings. Chapter 4 presents the process evaluation findings, and we discuss the findings and implications in Chapter 5.

Chapter 2 Methods and analyses

Overall study design

This was a cluster RCT with an embedded economic and mixed-methods process evaluation. The unit of recruitment and randomisation was the school, as this was an intervention that operated across the whole school.

The trial was registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Register (reference ISRCTRN95909211). We published the protocol on 18 October 2016. 63 We made some small changes to the protocol since it was originally submitted, which are summarised in Table 1. The full statistical analysis plan is available at URL: www.bristol.ac.uk/population-health-sciences/projects/wise/publications/ (accessed 5 November 2020).

| Change to protocol | Date |

|---|---|

| We were not able to recruit two schools per FSM stratum as planned; therefore, in both England and Wales, we had to merge strata. Further details on how the final sample fitted the FSM strata are included in Chapter 3 | May 2016 |

| We recruited one school more than our original sample size target (in case of drop-out) | June 2016 |

| Three schools at baseline and two at both follow-up time points were unable to secure meeting time for the team to administer the teacher questionnaires. These were, therefore, completed in teachers’ own time in these schools | June 2016 |

| We changed our safety procedure and information to participants to say that if a teacher writes anything that suggests that their life is in danger, the study team will use the participant names with study ID list to identify that individual and write to them at their school, advising they seek help, but that we would not inform anyone at their school about this | July 2016 |

| We originally planned to hold feedback meetings with the peer supporters once a term, but to avoid this feedback becoming part of the intervention (which would not be sustainable for any future roll out), we changed this to two feedback meetings with just one or two peer supporters each time to minimise the influence on behaviour | December 2016 |

| In one intervention school, the 1-day training was not delivered until the summer term because of difficulties securing a date for this | June 2017 |

| Data entry staff were not blinded to study arm as the questionnaires at T1 and at T2 were different | July 2017 |

| The statistician and health economist were not blinded at the point of conducting the analysis because of team error in providing unblinded data with regard to study arm | July 2018 |

| In addition to asking peer supporters to recruit individuals who had used the service for interviews, we also included a slip of paper in the teacher T2 questionnaires asking for volunteers. In the end, we did not manage to conduct these interviews as we only had one response | July 2018 |

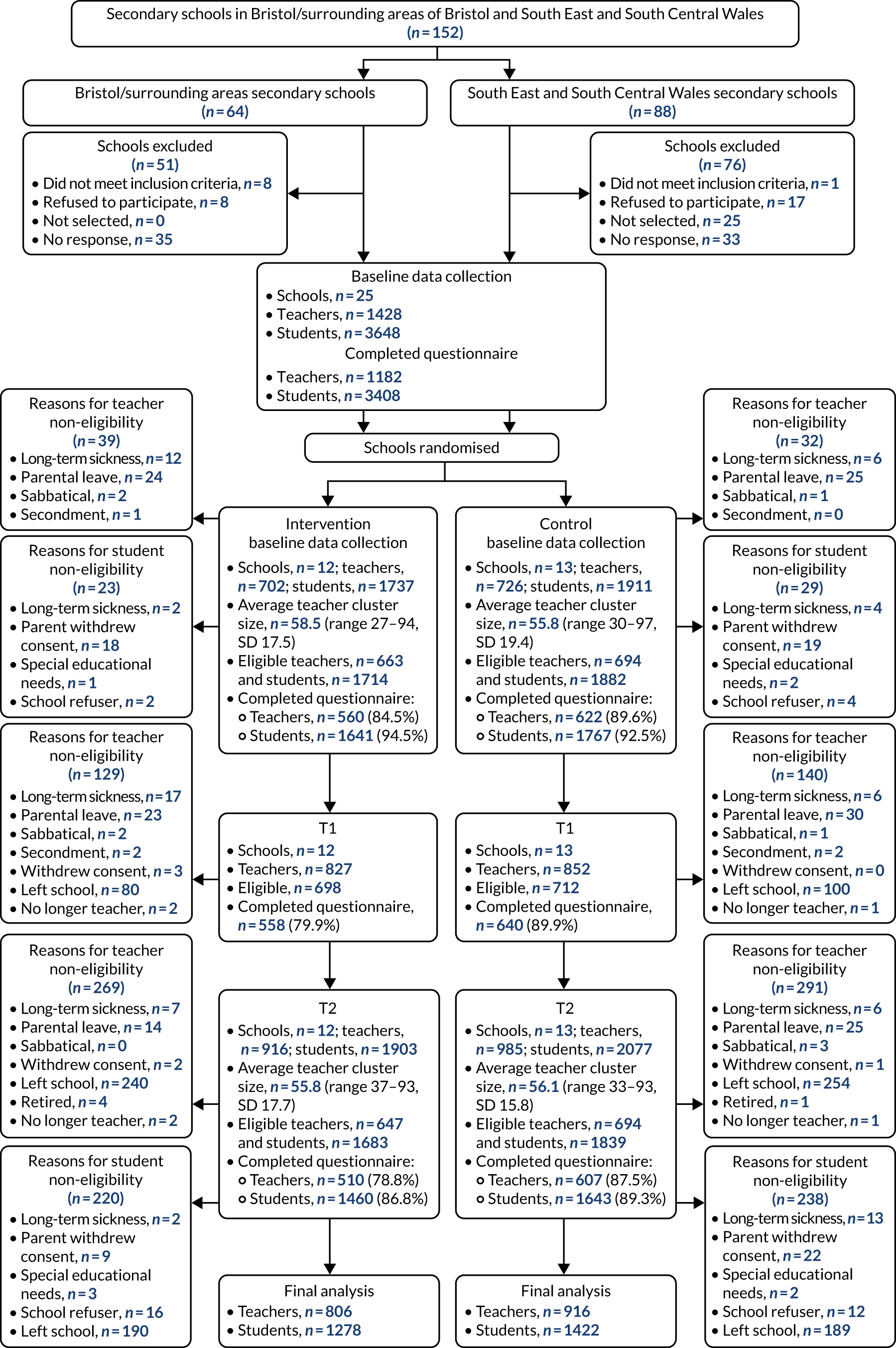

Study population

The population from which the schools in our sample were recruited was secondary schools in two geographical areas: (1) Bristol and surrounds up to a 30-mile radius, comprising 64 mainstream secondary schools and (2) South East and South Central Wales, comprising 88 mainstream secondary schools. Exclusion criteria were as follows:

-

fee-paying schools

-

special schools (e.g. for those with learning disabilities)

-

pupil referral units

-

schools that had been WISE pilot schools

-

schools participating in other, similarly intensive, research studies

-

schools already delivering MHFA or other mental health training

-

schools without available FSM data for stratification purposes

-

schools within the same academy chain and local authority as one that had already been selected for participation.

In total, we aimed to recruit 24 schools (i.e. 12 in each area).

Our study population within each school was all teaching staff and all students in year 8 (aged 12–13 years) at baseline. At 24-month follow-up (T2), the same students were year 10 (aged 14–15 years). We assumed that any effect on this year group would be the same for all students, as the intervention was intended to be at the whole-school level.

Recruitment and randomisation

In both England and Wales, the sampling frames were stratified by the proportion of children in each school who were eligible to receive FSM to ensure schools from a wide range of socioeconomic catchment areas were included in the study. In Wales, the sample was divided into two administrative regions (educational consortia), South East and South Central Wales, and schools were stratified into three FSM levels (high, medium and low vs. the national average). Two schools were randomly selected from each stratum in each region, and selected schools were approached via a relevant senior leader (e.g. a deputy head in charge of pastoral care) and invited to participate in the study. Schools that declined were replaced by a randomly selected school from the same stratum and region. In England, the study was advertised to head teachers at all eligible schools and invitations were followed up with relevant senior leaders, identified with the help of local public health teams that worked with the schools. Those who expressed interest in participation were stratified into three levels according to FSM (high, medium and low vs. the national average) and local authority (Bristol/non-Bristol). When more than two schools fitted into one stratum, two were randomly selected.

Within each study area and stratum, selected schools were randomly allocated to a study arm. Sequence allocation was generated by the study statistician, who was blinded to the schools’ identities, using the Stata ralloc command (version 14, StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Random allocation to study arm took place after baseline data collection.

Main outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was teacher well-being, measured using the Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS). 62 The WEMWBS is comprehensive (incorporating elements of both subjective and psychological well-being), short enough to be used in population-level questionnaires, responsive to change and validated among community samples of adults in the UK. [Licenses to use the WEMWBS are available at https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/sci/med/research/platform/wemwbs/using/ (accessed 11 February 2021).] We selected well-being rather than a measure of mental health difficulty as the primary outcome because it is a broad enough measure to capture changes among staff with a range of mental health needs, including those who have good well-being, but may still benefit from cultural changes at the whole-school level.

The WEMWBS scores can range from 14 to 70, where a higher score indicates better well-being. This outcome was measured at baseline, T1 and T2.

Secondary outcomes

Teacher depression was measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire-8 items (PHQ-8). 64 The PHQ-8 is suitable for measuring levels of depressive symptoms in population-based studies and is short enough to be used in self-complete questionnaires. It was analysed as a continuous variable, but also as an ordinal variable (0–4 indicating no depressive symptoms, 5–9 indicating mild symptoms, 10–14 indicating moderate symptoms, 15–19 indicating moderately severe symptoms and 20–24 indicating severe symptoms) and a binary variable, with a cut-off point of ≥ 10 indicating depression. 64 These cut-off points were established for the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items, but are the same for the PHQ-8, with the only difference between the two scales being an additional question about self-harm behaviour, which does not contribute to the overall depression score.

Teacher absence was measured by self-report (i.e. the ‘number of days missed from school because of health problems in the past 4 working weeks’) and routine data collected by the schools (i.e. the total number of days of absence over the previous year). Both measures were treated as continuous, but the self-report measure was also treated as binary (any vs. no absence) and ordinal. Based on the distribution of responses in the pilot study, in which the majority of respondents had taken very little absence, categories were 0 days, 1 day, 2–7 days or ≥ 7 days.

Teacher presenteeism was measured by self-report, using the relevant item from the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment questionnaire65 and adapted to fit teachers’ work schedule. Teachers were asked ‘during the last 4 working weeks, how much did health problems affect your productivity while you were working?’ and selected a number between 0 (no effect) and 10 (completely prevented me from working). This measure was treated as continuous, but also as binary (no effect vs. 1–10 effect on work over the previous 4 working weeks) and ordinal. Based on the pilot responses to presenteeism, in which roughly one-third of participants scored 0 and a majority scored < 6, the categories were 0 days, 1–5 days or 6–10 days.

Teacher retirements and leaving for other reasons were collected as total number reported by the schools for the previous year.

Year 8 student well-being was measured using the WEMWBS, which has been validated for use among teenagers from age 13 years. 66 This measure was treated as continuous.

Year 8 student psychological distress was measured using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), a widely used measure among this age group, with well-established norms for a UK population. 67 A total difficulties score was calculated (this can range from 0 to 40, with a higher score indicating greater difficulties) and treated as continuous.

Student attendance was collected as a total proportion for each school from routine data sources for England68 and Wales. 69

Student attainment at the end of year 11 was collected from the same routine data sources as student attendance. 68,69 Exams at the end of statutory school age (key stage 4) are graded and reported differently for the two countries. For English schools, we reported per cent of students achieving grade 5 or above in both English and Maths General Certificates of Secondary Education, and for Welsh schools we reported per cent of students achieving grade C or above in English/Welsh, Maths and Science GSCEs.

The baseline questionnaires are included in Appendices 1 and 2.

Outcome data collection process

Teacher self-report outcome questionnaires were completed during staff meetings at baseline (May–July 2016), T1 (May–July 2017) and T2 (May–July 2018). Those who were absent from the data collection session were offered the option of completion via an online survey. Data on teacher absence, retirement and leaving for other reasons were collected via routine data recorded by the schools.

Student mental health outcomes were gathered via self-report questionnaires at baseline and T2, completed by all students in year 8 (aged 12–13 years at baseline), during tutor groups or lesson time. Where fewer than five students were absent, questionnaires were left with school for those students. Where five or more students were absent, a second data collection was arranged with schools. School-level student absence and attainment were collected using government statistics published online.

Teacher routine outcomes (school-reported absence and leavers data) and all student outcomes were measured at baseline and T2 only. This was for practical reasons, and also because the intervention’s logic model implied that teacher mental health would need to improve before changes to student mental health were maximised.

The study team planned to attend all data collections, introduce the questionnaires, answer any questions and take them away at the end. However, three schools at baseline did not manage to secure meeting time to conduct the data collections. In these schools, the team briefly introduced the questionnaires in a meeting, but left them with staff along with envelopes in which questionnaires could be sealed and then either posted or returned via a box left at the school. Two of these schools followed the same process at both T1 and T2, despite attempts by the study team to organise meeting time.

Compliance and loss to follow-up

We encouraged the schools to set the dates for data collection sessions far in advance to try and ensure maximum attendance. We built in time to follow up those who were absent, either in person or by leaving questionnaires in named envelopes, which the research team collected once completed. We also made an online version of the questionnaire available to teachers who missed the data collection session. We incentivised schools to remain part of the study by providing them with their own school-level data from each time point at the end of the study. We also offered control schools a payment at the end of the study, which they could choose to spend on the intervention if it was found to be effective. This payment was contingent on a response rate of at least 80% at follow-up among teachers and students.

Sample size

The study was powered to detect a mean change of 3 points on the WEMWBS (i.e. the primary outcome measure). This difference was chosen as the minimum meaningful change discussed in a WEMWBS user guide. 70

A change of 3 points was also close to the difference in mean WEMWBS scores between staff in the highest- and lowest-ranked schools in the pilot study.

It was estimated that each school would have approximately 60 teachers and 150 year 8 students, depending on size. The sample size took account of clustering. In the pilot data, the teacher WEMWBS intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) at baseline was 0.01 (95% CI 0.00 to 0.03) and at follow-up it was 0.00 (95% CI 0.0 to 0.02). We assumed a mean of 50 (83%) teachers followed up per school (with a coefficient of variation of sample size of 0.5) and a standard deviation (SD) for WEMWBS of 8.4 (based on the pilot data). A sample size of 24 schools (i.e. 12 intervention schools and 12 control schools) would achieve 83% power for an ICC of 0.05. This would rise to 98% if the ICC is 0.02, and fall to 65% for an ICC of 0.08. Sample sizes were calculated using the clustersampsi command in Stata. For the tests for interactions (see Main outcomes analysis), we would have 80% power to detect an interaction that is twice as big as the main effect, and 30% power to detect an interaction that is the same size as the main effect. 71

Blinding and breaking of blind

Allocation to study arm took place after baseline data had been collected to ensure blinding among all parties during this first data collection. It was not possible for the schools, teachers or students to be blind to intervention status (although students were likely to be unaware of the intervention). The research assistants/associates leading outcome data collection also collected the process data, which prevented blinding among the study team.

Clustering

All statistical analyses took account of clustering by school using robust standard errors and, where appropriate, by using random-effects models with schools as a random effect. Analyses were conducted using Stata.

Main outcomes analysis

Primary analysis

The primary analysis was carried out under the intention-to-treat principle, analysing participants as randomised without the imputation of missing data. Repeated-measures (random-effects) models were used to examine pattern of change in primary outcome over baseline, T1 and T2, adjusted for stratification variables, sex and years of experience. This included a random effect for individual participants and another for school. This model included every teacher who had at least one measure of the outcome (i.e. at baseline, T1 or T2). Using a maximum likelihood estimator, this analysis was robust to data that are missing at random (MAR). 72,73 Results are presented in Chapter 3 as mean difference in the primary outcome between the trial arms over the follow-up period, with associated 95% CIs and p-values.

The primary analysis was repeated with a treatment by time interaction term added to the model. This allowed estimation of treatment effect at T1 and T2 separately.

Secondary analyses

Analysis of secondary outcomes included linear, ordinal and logistic regression models, dependent on the nature of the outcome variable being analysed (continuous, ordinal or binary, respectively).

For secondary individual-level outcomes that are measured at baseline, T1 and T2 (e.g. PHQ-8), repeated-measures models were used and these models included random effects for clustering by individual (because of repeated measure) and by school. All individuals with at least one observation of the outcome measure were included in the model for that outcome using maximum likelihood under a MAR assumption. For each secondary individual-level outcome that was measured at baseline, T1 and T2, three models are presented:

-

Unadjusted model (model 1): repeated measures of the outcome regressed on treatment arm, accounting for clustering because of repeated measures and by school (using random effects).

-

Partially adjusted model (model 2): model 1 plus adjustment for stratification variables.

-

Fully adjusted model (model 3): model 2 plus additional adjustment for the covariates sex and years of teaching experience.

For each secondary individual-level outcome measured at baseline and T2 only, three models are presented:

-

Unadjusted model (model 1): outcome at T2 regressed on treatment arm and baseline value of the outcome, accounting for clustering by school (using a random effect).

-

Partially adjusted model (model 2): model 1 plus adjustment for stratification variables.

-

Fully adjusted model (model 3): model 2 plus additional adjustment for sex and ethnicity as covariates.

For each secondary school-level outcome measured at baseline and T2 only, two models are presented:

-

Unadjusted model (model 1) – outcome at T2 regressed on treatment arm and baseline value of the outcome (no need for any adjustment for clustering).

-

Adjusted model (model 2) – model 1 plus adjustment for stratification variables.

Missing data

We assessed the impact of missing data and non-response on teacher WEMWBS and PHQ-8 outcomes and student WEMWBS and SDQ outcomes using multiple imputation. The multiple imputation model73 included all outcomes at baseline, T1 and T2, variables included in the primary analysis model and baseline characteristics associated with missingness. Analyses were repeated on the imputed data sets and results were combined using Rubin’s rules. We also used sensitivity analyses to examine the impact of potential missing not at random (MNAR) data by incorporating a scaling parameter that was allowed to differ between arms (i.e. allowing the missing data mechanism to differ between arms). 74 This was carried out by imputing under the MAR assumption and then multiplying imputed values of the outcome by a scaling parameter. For example, a scaling parameter of 0.95 in the control arm and 0.90 in the intervention arm implies that missing WEMWBS scores in the control arm are assumed to be 5% lower than estimated under a MAR assumption, whereas scores in the intervention arm are 10% lower.

Sensitivity analyses

We re-ran the primary analysis without identified outliers (defined as a WEMWBS score > 3 SDs from the mean) to assess the effect of outliers on the main outcome.

Subgroup analysis

We used a complier-average causal effect (CACE) approach (using instrumental variable analysis)75 to examine the impact of MHFA training on follow-up WEMWBS and PHQ-8 scores, comparing those who completed the 1 or 2 days, training in the intervention schools with those in the control schools who would have completed the training, had they been offered it. For each participant, we calculated a summary score of the two outcomes and used the summary score to account for the repeated measurements (therefore reducing the two measures to a single measure). If only a single measure was available then we used just the single measure. We included robust standard errors to account for clustering at the school level.

Tests for interactions

The effect of the intervention on teacher WEMWBS and PHQ-8 score was tested for interaction with baseline well-being/depression score (grouped as above or below the bottom quartile of the WEMWBS, or with a score of ≥ 10 on the PHQ-8), geographical area (Wales/England), school-level FSM and sex. The effect of the intervention on student WEMWBS and SDQ score was tested for interaction with baseline well-being/SDQ score (grouped as above or below the bottom quartile of the WEMWBS and a score of ≥ 20 on the SDQ), geographical area, school- and individual-level FSM, sex and ethnicity. p-values were interpreted with caution because of the low power and number of interactions being tested (we used Bonferroni corrected or permutation p-values).

Exploratory analysis: mechanisms of change

To explore the study’s logic model and hypothesised mechanisms of change, we collected data in the teachers’ questionnaires regarding stress and satisfaction at work, support given/received at school, school’s perceived attitude to staff and student well-being, and perceived quality of relationships in school. These questions were asked with a series of Likert responses (see Appendix 2 for full wording and response options). Logistic regression models were used to compare binary measures of these variables between arms at follow-up adjusted for baseline scores, school-level FSM and geographical area. We examined whether or not baseline measures of these variables, which provide indicators of school psychosocial context, moderate the effect of the intervention by including interaction terms between these baseline variables and intervention arm in the analysis model.

Appropriate mixed models were applied as for the primary analysis, but, additionally, these measures were included as covariates. We assessed the degree to which the estimated treatment effect attenuated compared with our chief analysis model (substantial attenuation would indicate the proposed mechanisms of change are indeed acting as such).

Exploratory analysis: level of intervention

Data from the process evaluation [i.e. training participant evaluation forms, peer supporter feedback meetings, peer supporter logs of support and follow-up questionnaires (see Process evaluation for more detail)] were used to divide intervention schools into ‘low’ or ‘high’ implementation groups. Factors, measured as binary variables, that were used for this analysis were as follows.

Dosage

-

At least 8% of teachers completed the 1-day MHFA for schools and colleges training (vs. < 8% of teachers).

-

At least 8% of staff in the school completed the 2-day standard MHFA training and went on to become a peer supporter (vs. < 8% of staff).

-

At least 8% of staff in the school still acting as peer supporters by T2 (vs. < 8% of staff).

Reach

-

At least 75% of teachers attended the 1-hour awareness training (vs. < 75% of teachers).

-

Higher than study mean for those who select ‘staff peer supporter’ in response to the question ‘if a work-related problem was making you stressed or down who would you talk to about it at school?’ in the follow-up questionnaires.

Fidelity

-

100% of course attendees indicated that all topics were covered in the 1-day MHFA for schools and colleges training and 2-day standard MHFA training (vs. < 100%).

-

The peer supporters set up a confidentiality policy for the service (vs. no policy).

-

The peer support service was advertised in three or more ways initially (vs. advertised in two or fewer ways).

-

The peer support service was re-advertised at the beginning of the 2017–18 academic year (vs. not re-advertised).

-

The peer support service had been championed by a member of the senior leadership team (vs. not championed).

Correlation between all the implementation measures was poor and so we were unable to determine one composite binary measure ‘low/high implementer’. Instead, we scored each school on each factor and split the schools based on their total scores, with the six highest being high implementers and the six lowest being low implementers. We then compared primary outcomes among intervention schools that were high implementers with those that were low implementers. We repeated this analysis with implementation as a continuous variable. Adjustment was made for both school- and individual-level covariates, as in the primary analysis.

Economic evaluation

Measurements

The economic analysis took a public sector perspective, calculating the financial and opportunity costs to schools of participating in the WISE intervention. We collected self-reported information on the impact of teachers’ health on absenteeism and presenteeism during the previous 4 weeks at T1 and T2. However, in common with other school-based interventions,76 we elected not to track teacher health-care use at T1 or T2.

Data were collected on the resources used for the following four activities: (1) the HSC MHFA instructor training (which was relevant for Welsh schools only); (2) the 2-day standard MHFA training; (3) the in-service day MHFA training for schools and colleges; and (4) the awareness raising session. In each case, the project team completed a pro forma after the training session, documenting the resources used and expenses claimed.

As noted in Chapter 1, in Wales, Public Health Wales paid for a course to train seven HSCs as MHFA instructors who could then deliver the MHFA training to teachers in Welsh schools. The course included 6 days of training with a MHFA trainer and 2 additional days of independent preparation for the HSC trainees. The costs comprised HSCs’ time (estimated based on salary costs), actual travel expenses incurred, MHFA course fees, MHFA trainer expenses and course refreshments. The venue was provided at no cost by Cardiff University (Cardiff, UK).

The resources used during the 2-day standard MHFA training comprised MHFA trainer fees, trainer travel expenses (in English schools this was sometimes included in the trainer fee), MHFA manuals, refreshments (in most schools) and the time of the teachers being trained as peer supporters (a minimum of five teachers and a maximum of 16 teachers). There were no venue costs for training, as this happened either on the school site or at a university. Several schools provided estimates of the cost of hiring supply teachers to cover the teaching commitments of staff attending the MHFA training. We used these estimates to impute the opportunity cost of staff time at all schools.

The resources used for the 1-day MHFA schools and colleges training comprised MHFA trainer fees, trainer travel expenses (in English schools this was sometimes included in the trainer fee), MHFA manuals and the time of the teachers attending training (a minimum of seven teachers and a maximum of 18 teachers). As training took place during in-service days, no supply teachers were necessary and staff costs were estimated based on anonymised salary information provided by the schools. When salary information was not provided by the school (n = 1), these costs were imputed based on the number of attendees and the mean salaries of attendees from other schools.

The resources used for the 1-hour awareness raising session for all teachers comprised the trainer fees, and travel costs and the staff costs for the teacher and support staff attending. For the English schools, staff costs were estimated from the number of staff attending (a minimum of 31 staff and a maximum of 85 staff) and estimated salaries were based on salary band information provided by schools. The mean school staff costs in England were used to impute the staff costs in Welsh schools, where data on staff attendance was not available.

All resource use was valued in monetary terms using published UK unit costs (Table 2) or participant valuations estimated at the time of analysis (2016/17). Support staff salaries were obtained by asking schools/individuals for this information. Teachers’ salaries were estimated using national pay scales after confirming participants’ pay bands.

| Description | Unit cost | Source |

|---|---|---|

| HSCs MHFA instructor training (Wales only) | ||

| MHFA course fee | £11,632 | Expenses recorded |

| Trainer’s costs | £79.43 per day plus subsistence and parking | Expenses recorded |

| HSC time | £18.40–20.47 per hour | Estimate based on HSC salaries |

| Travel/parking | Variable | Trainer and trainee expense forms |

| Catering | £58.80 per day | Based on expenses recorded |

| 2-day peer supporter MHFA training | ||

| HSC time (Wales only) | £18.40 per hour | Estimate based on HSC salaries |

| MHFA manuals (Wales only) | £18–20 per manual | Total cost based on number of peer supporters trained |

| MHFA trainer fees including manuals (England only) | £420–650 per day | Based on expenses recorded |

| Catering | £60 per day | Based on expenses recorded |

| Travel/parking | Variable | Trainer and trainee expense forms |

| Teaching cover | Variable | Based on school reports of expenses paid to supply teachers |

| In-service day MHFA for schools and colleges training | ||

| HSC time (Wales only) | £18.40 per hour | Estimate based on HSC salaries |

| MHFA manuals (Wales only) | £18–20 per manual | Total cost based on number of peer supporters trained |

| MHFA trainer fees including manuals (England only) | £600–750 per day | Based on expenses recorded |

| Travel/parking | Variable | Trainer and trainee expense forms |

| Awareness raising session fees | ||

| HSC time (Wales only) | £18.40 per hour | Estimate based on HSC salaries |

| MHFA trainer fees (England only) | £260–350 per session | Based on expenses recorded |

| Travel/parking | Variable | Trainer expense forms |

Cost–consequence analysis

The economic evaluation is a cost–consequence study that provides evidence on whether or not the incremental costs of the intervention are justified because of improved teacher or student outcomes. The potential benefits of the intervention are multifaceted and affect multiple agents (e.g. staff, students and schools), even those not directly observed in the study (e.g. students in other years). Therefore, a cost–consequence framework that tabulates costs against several outcomes for staff and students is appropriate, rather than a more reductive cost-effectiveness or cost–utility analysis that attempts to summarise efficiency in a single ratio. 77 It provides a more complete analysis for policy-makers than a ‘cost per unit improvement in WEMWBS score’, which has no easy interpretation. Previous research has demonstrated limited correlation and overlap between the WEMWBS well-being scores and health-related utility scores (such as the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version) used to estimate quality-adjusted life-years. 78 As quality-adjusted life-years are unlikely to be sensitive to small changes in well-being, we did not include the EuroQol-5 Dimensions or other preference-based health-related quality-of-life measures.

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analysis is reported by country to investigate any differences in findings between England and Wales. This is important, given that the costs and, potentially, the outcomes will differ because of the different use of MHFA trainers in England and Wales.

Process evaluation

Aims

A mixed-method process evaluation was integrated into the outcome and economic evaluations,79 following a ‘nested’ design. 80 The primary aim of the process evaluation was to support the interpretation of the outcome data and further refine the programme theory. 81 The process evaluation had five central objectives, which, for the purpose of the study, were categorised as domains of inquiry. These were as follows.

Implementation

The aim was to assess the implementation of the intervention, using a multicomponent framework.

Implementation is assessed separately for the MHFA for schools and colleges and standard MHFA training courses provided for schools, and the delivery of the peer support services. For the training, the aim was to assess (1) reach (i.e. the number who attended), (2) dose (i.e. the completion of the training), (3) fidelity to the course and adaptations undertaken, (4) variations in fidelity between schools in England and Wales, and (5) quality of training delivery. For delivery of the peer support service, the aim was to assess (1) reach (i.e. the proportion of teachers who make use of the peer support service), (2) fidelity to the peer support service model and adaptations undertaken, and (3) contextual characteristics that determined barriers to and facilitators of implementation.

Mechanisms of change

The aim was to explore if the intervention’s hypothesised mechanisms of change were activated as intended, and the extent to which these mechanisms were modified through their interaction with contextual characteristics. Postulated mechanisms, refined through the feasibility and pilot phase of intervention evaluation, are depicted in the logic model (see Figure 1). We also considered unintended consequences and, in particular, unanticipated harms and the pathways by which these may have occurred. 82

Programme differentiation and contamination

The aim was to understand usual practice to assess programme differentiation and ascertain if contamination had occurred in control schools.

Sustainability of the intervention

The aim was to assess the extent to which the intervention is sustainable and its scope to become routinised as part of usual practice outside a trial setting.

Acceptability

The aim was to explore participants’ perceptions of and interactions with the intervention components, and how this differed across school contexts and across the course of delivery. The purpose of exploring intervention acceptability was to understand if and in what ways its acceptability to participants influenced the operationalisation of the mechanisms of change. Therefore, it is explored as an embedded theme throughout the process evaluation results in Chapter 4, rather than as a discreet theme.

Research questions

Table 3 lists the research questions that the process evaluation addressed and outlines the domain of inquiry to which each one was aligned.

| RQ | Process evaluation domain |

|---|---|

|

RQ1. Are the intervention’s mechanisms of change operationalised as hypothesised? RQ2. How is the operationalisation of the mechanisms of change influenced by contextual factors? RQ3. Does the interaction of the mechanisms of change with contextual factors give rise to unintended effects? |

Mechanisms of change |

|

RQ4. Is the WISE intervention differentiable from ‘usual practice’ and does this differentiation change during the study? RQ5. Is there contamination of usual practice in control schools by receipt of the WISE intervention or similar approaches? |

Programme differentiation and usual practice |

|

RQ6. What is the reach of the WISE training components (e.g. 8% of staff attending standard MHFA)? RQ7. How many targeted staff complete the WISE intervention training (dose)? RQ8. Are the WISE training components delivered with fidelity and what is the nature of any modifications undertaken? RQ9. Are there differences in the delivery of the WISE training components between England and Wales, and what gives rise to any differences? RQ10. How well are the WISE training components delivered? |

Implementation (WISE training components) |

|

RQ11. What proportion of teachers receive support from the peer support service? RQ12. Is the peer support service delivered with fidelity and what is the nature of any adaptions undertaken? RQ13. What are the barriers to and facilitators of the implementation of the peer support service? |

Implementation (peer support service) |

| RQ14. Is the WISE intervention acceptable to funding organisations, intervention trainers, head teachers, teachers and students? | Acceptability |

| RQ15. How likely is the WISE intervention to be sustainable and what factors might ensure sustainability? | Sustainability |

Sample

Four intervention schools and four control schools were purposively sampled to serve as ‘case study schools’, in which more extensive process evaluation was undertaken (e.g. focus groups and observations). To sample the case study schools, all study schools were stratified by trial arm allocation (intervention vs. control), site (England vs. Wales), administrative region (educational consortia vs. local authority) and proportion of students eligible for FSM (high/low vs. the national average). One intervention school within each stratum was then purposively sampled to achieve variation across the cases in school size and assessment ranking by the educational inspectorate. One control school was selected within each stratum to match the intervention cases as closely as possible. Table 4 presents the final sample of case study schools.

| School | Trial status | Site | Administrative region | FSM eligibility | School size | Inspectorate assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Intervention | England | 1 | Low | Large | Good |

| 2 | Intervention | England | 2 | High | Small | Requires improvement |

| 3 | Intervention | Wales | 3 | High | Small | Adequate |

| 4 | Intervention | Wales | 4 | Low | Large | Good with outstanding features |

| 5 | Control | England | 1 | Low | Large | Requires improvement |

| 6 | Control | England | 2 | High | Small | Good |

| 7 | Control | Wales | 3 | High | Small | Adequate |

| 8 | Control | Wales | 4 | Low | Large | Good |

Data sources

The process evaluation adopted a mixed-methods approach and used both quantitative and qualitative data sources. The different types of data collected from the study schools, and how they relate to the research questions, are summarised in Report Supplementary Material 3.

Teacher and student questionnaires

The teacher and student questionnaires that were designed to collect the main outcome data also contained questions relating to the mechanisms of change domain of inquiry. As already noted in Main outcomes, the teacher questionnaires asked about stress and satisfaction at work, quality of relationships between teachers and students and between staff, whether or not the school cares about teacher well-being and how much individuals had given support to colleagues over the previous year. The questionnaire also asked about perceptions of how much their school cared about student well-being and the extent to which they had supported students in the previous year. Follow-up questionnaires in the intervention group only also examined intervention reach (i.e. the numbers who had completed MHFA training and who had received support from the peer supporters) as part of the implementation domain of inquiry. The student questionnaires asked about perceptions of the extent to which the school and teachers cared about students, how often individuals had asked a teacher for help over the previous year and whether or not this had been useful.

Audit of school policies and interventions

Participating schools were audited at baseline and T2 (see Report Supplementary Material 4 for a copy of the audit questions). The main contact teacher for each school reported on existing policies and interventions within the school in relation to the mental health and well-being of teachers and students. The baseline audit allowed for comparison of pre-existing activities in intervention and control schools to explore possible baseline imbalances and to understand the general context in which the intervention was being delivered. The T2 audit captured relevant policies or interventions that had been introduced during the study period. It therefore enabled exploration of programme differentiation from usual practice in intervention schools and assessment of contamination in the control schools by identifying any new activities that were similar to components of the WISE intervention. An additional question was included in the follow-up audits that asked about any key events that had occurred during the study that were likely to have an impact on mental health and well-being. This, again, enabled consideration of the impact of the context on any intervention effects.

Attendance records for the Wellbeing in Secondary Education intervention training

The MHFA course instructors completed an attendance record for each training course, which enabled an assessment of reach of the training. Instructors also conducted a head count of staff attending the 1-hour awareness raising session; however, some schools opened this session to all teaching and non-teaching staff, and, therefore, it was not possible to calculate the proportion of teaching staff that attended these sessions.

Observations of the Wellbeing in Secondary Education intervention training

In the four intervention case study schools, two members of the research team observed the 1-hour awareness raising session, the 2-day MHFA training course for peer supporters and the 1-day MHFA for schools and colleges course. Standardised observation schedules (see Report Supplementary Material 2 for an example of a template) were completed to quantitatively assess coverage of materials (yes/no for each topic), quality of delivery and participant engagement (5-point Likert scales). Observers also qualitatively documented any information relevant to understanding the quantitative assessment and other issues of importance not covered by the quantitative scale, including course adaptations and general contextual observations. This generated data relating to the implementation and acceptability domains of inquiry.

Post-mental health first aid training course fidelity checklist

In all 12 intervention schools, participants completed a checklist recording whether or not key topics were covered (yes/no), and rating the instructors knowledge and skills (5-point Likert scale). An example checklist is included in Report Supplementary Material 5. This enabled further consideration of the training implementation.

Training evaluation forms

Attendees of all MHFA training in the 12 intervention schools completed standardised MHFA evaluation forms. These forms recorded self-assessed knowledge and confidence to support others before and after the course, and views on course quality (5-point Likert scale).

Attendees of the 1-hour awareness raising session completed a study-specific evaluation form (see Report Supplementary Material 6) which asked them to rate how much their knowledge had improved (no impact, a small increase, a large increase) in relation to six topics and how highly they rated the instructor (5-point Likert scale). These data illuminated the mechanisms of change domain of inquiry.

Peer supporter logs and feedback sessions

The peer supporters completed a termly electronic log that documented delivery of support to colleagues during the previous 2 working weeks (see Report Supplementary Material 7). To mitigate the risk of seasonal bias (e.g. stress associated with end of term examinations), peer support logs were issued at different times during the academic term. The log assessed the reach (i.e. how many colleagues received support), the role of the staff members supported, the type of problem addressed (e.g. work or personal life), time of day and length of support episode, and the outcome of the interaction. The logs also invited peer supporters to provide any information about difficulties they had experienced as a peer supporter to allow monitoring of any harms. The log was used to record when peer supporters had left the school.

In addition, one or two peer supporters in all 12 intervention schools were invited to a feedback session approximately 6 months and 18 months after their training had been completed. The purpose of the feedback sessions was to assess the extent to which the peer support service guidelines had been adhered to, again shedding light on the implementation domain of inquiry. The sessions took the form of structured interviews (see Appendix 3 for the questions asked), with responses audio-recorded.

Interviews with mental health first aid instructors

As noted above, the 2-day, 1-day and 1-hour training sessions were delivered by independent MHFA instructors to English schools, and by HSCs employed by Public Health Wales or local authorities to Welsh schools. Semistructured interviews were conducted with the three MHFA instructors in England and a subgroup of three of the seven HSCs in Wales. The HSCs were purposively sampled to ensure that a representative from each of the six intervention schools was interviewed (HSCs delivered the intervention in pairs). Topic guides explored experiences of training delivery, including barriers to and facilitators of delivering a successful session, the extent to which instructors adhered to the course and motivations for any adaptations undertaken. In addition, the perceived acceptability of the training to course participants was also explored.

Interviews with head teachers

Semistructured interviews were conducted with the head teachers from all 25 schools. Topic guides explored the perceived role of schools in addressing the mental health and well-being of staff and students, the acceptability of usual practice, motivations to take part in the study, and the barriers to and facilitators of supporting teacher and student mental health. These data contributed to understanding of the acceptability and sustainability of the intervention.

Interviews with peer support service users

In the four intervention case study schools, we had planned to conduct semistructured interviews with teachers who had utilised the peer support service. However, despite trying a number of methods to recruit volunteers (e.g. the peer supporters asking colleagues they had helped, putting reply slips in the teacher questionnaires) we had only one volunteer and so we did not complete this part of the data collection.

Focus groups with peer supporters and recipients of mental health first aid for schools and colleges training

In the four intervention case study schools, focus groups were conducted with peer supporters and with teachers who had attended the MHFA for schools and colleges training. A focus group was conducted with each group within 6 months of training delivery, and a second focus group was conducted with each group approximately 18 months after training delivery. For the selection of participants for the focus groups, convenience sampling was used (i.e. all trainees in the case study schools were invited to attend and the actual make up of each group was determined by availability). Focus groups comprised four to eight participants.

Focus groups with peer supporters explored the acceptability of MHFA training and attendees’ preparedness to become peer supporters, the acceptability of delivering support, barriers to and facilitators of implementation of the peer support service, fidelity to the guidelines and reasons for adaptations undertaken, and sustainability of the intervention. Focus groups with 1-day MHFA for schools and colleges trainees covered the acceptability of and potential improvements to the training, impact of the training on how participants interacted with and supported students, and sustainability of the intervention. At the second time point, 18 months after training delivery, one-to-one interviews were conducted in place of a focus group in one school because of logistical difficulties in organising a focus group, but the same questions were explored.

Focus groups with teachers not in receipt of the mental health first aid training

It was planned to conduct one focus group in each of the four intervention and four control case study schools with teachers who did not receive any MHFA training, approximately 18 months after training delivery. For selection of the focus groups, random sampling was used (i.e. all teachers in the school were stratified according to sex and department, and participants were randomly selected from each stratum using random number generation software). If someone declined to participate, a replacement was randomly selected from the same strata until eight participants had been confirmed. Each focus group comprised six to eight teachers. In one intervention school, a one-to-one interview was held, as a focus group was too difficult to organise. In the intervention schools, focus groups explored participants’ views of the peer support service (including comparison with ‘usual care’), perceived barriers to and facilitators of uptake, and potential service sustainability. In the control schools, focus groups explored evidence of contamination, perceptions of ‘usual practice’ and views on a hypothetical peer support service.

Focus groups with year 10 students