Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 14/21/45. The contractual start date was in December 2015. The final report began editorial review in September 2019 and was accepted for publication in December 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research, or similar, and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2022. This work was produced by Oulton et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health and Care Research, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2022 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Easy-read summary

Structure of the report

This report of the findings from the Pay More Attention study has four sections.

Section 1

The introduction comprises three chapters, focusing on the background to the study (see Chapter 1), the study aims and theoretical framework (see Chapter 2) and the literature review (see Chapter 3).

Section 2

Research design and methods of data collection and analysis for each phase (see Chapter 4).

Section 3

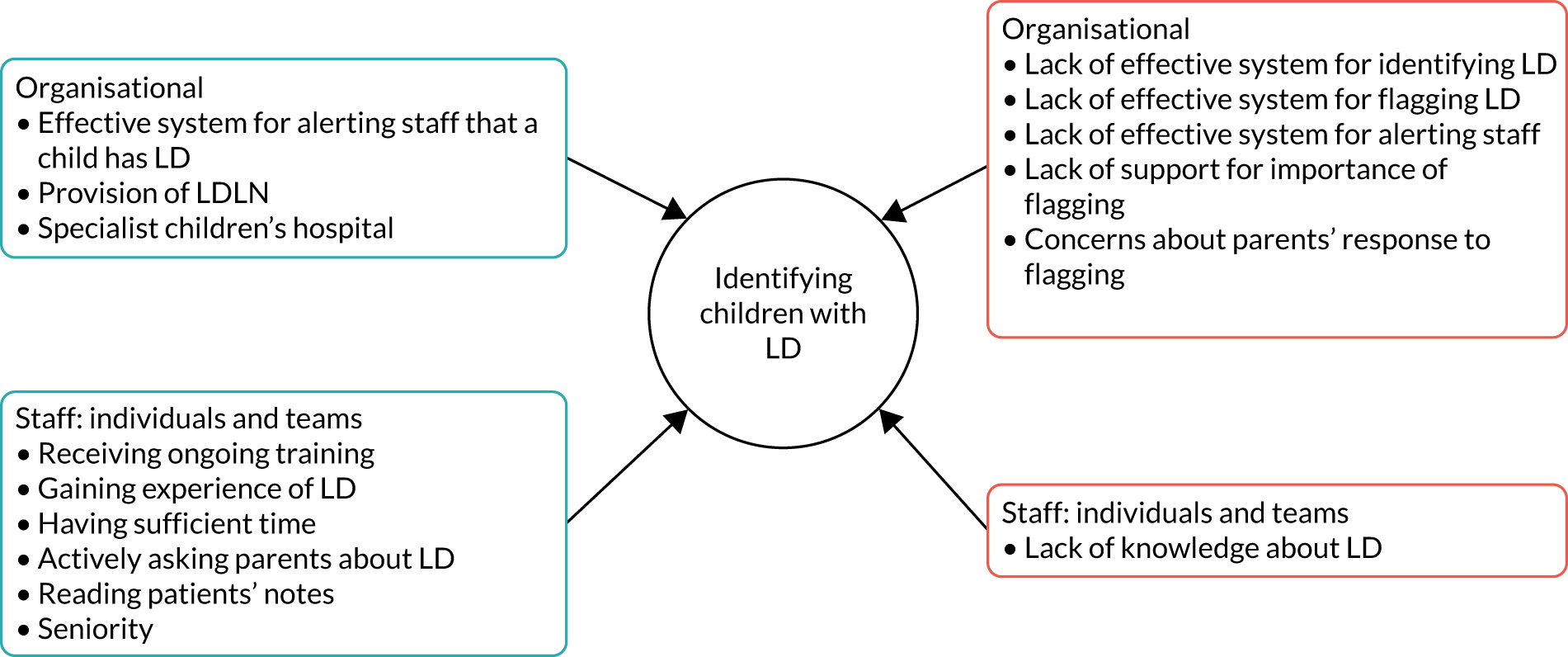

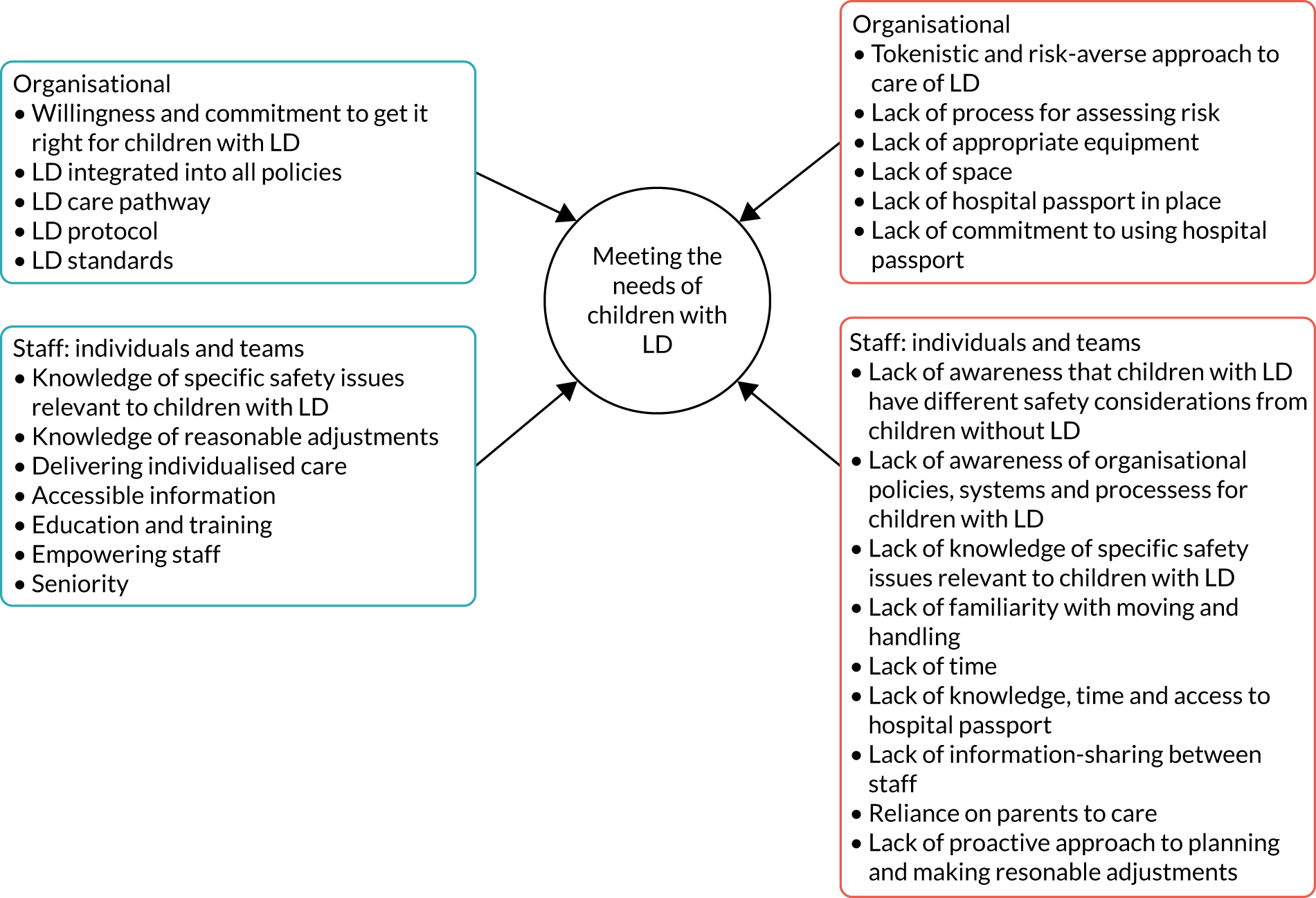

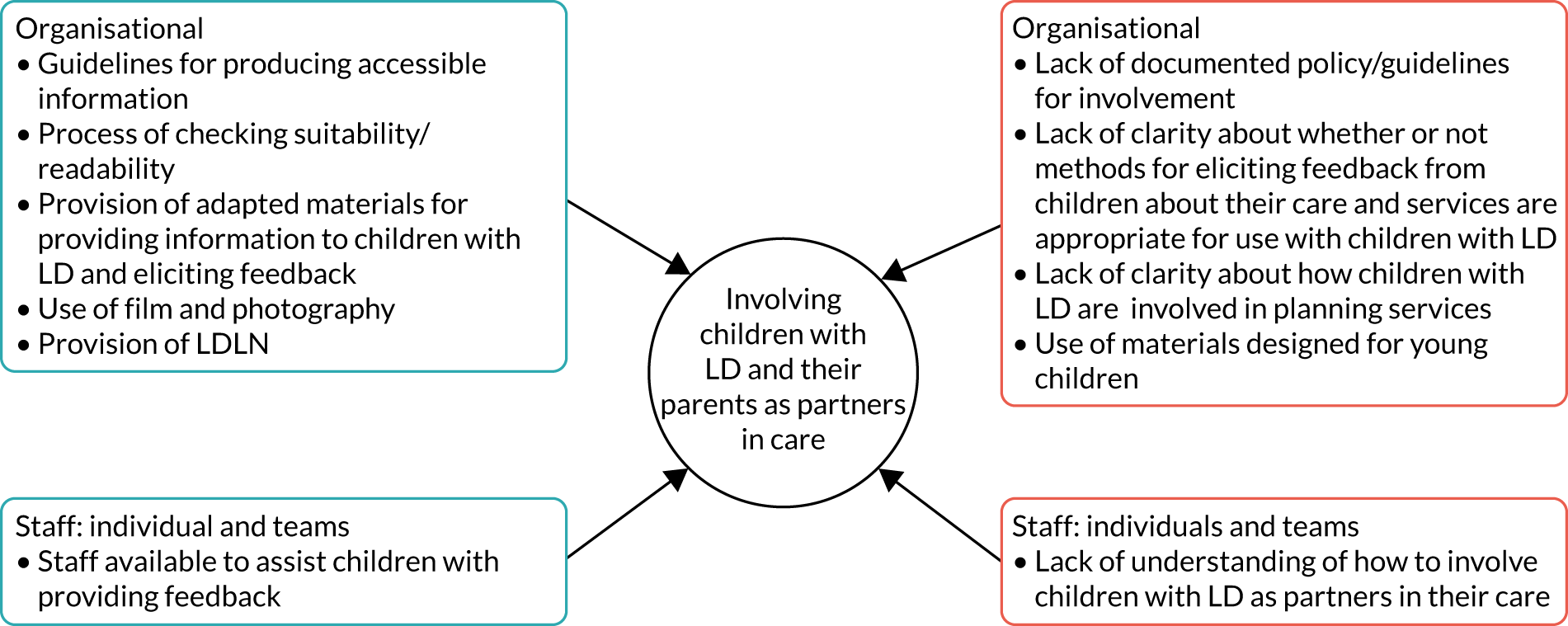

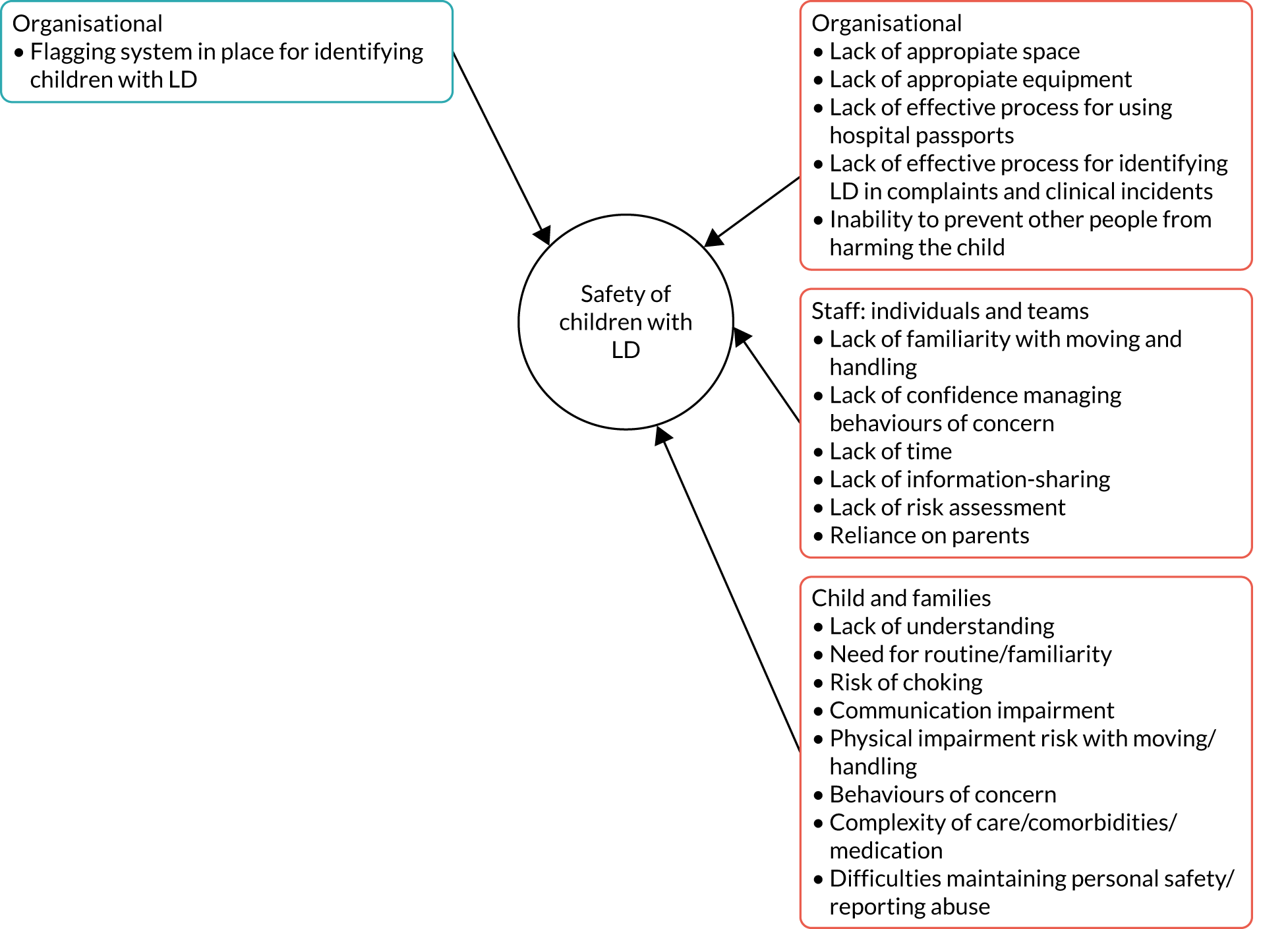

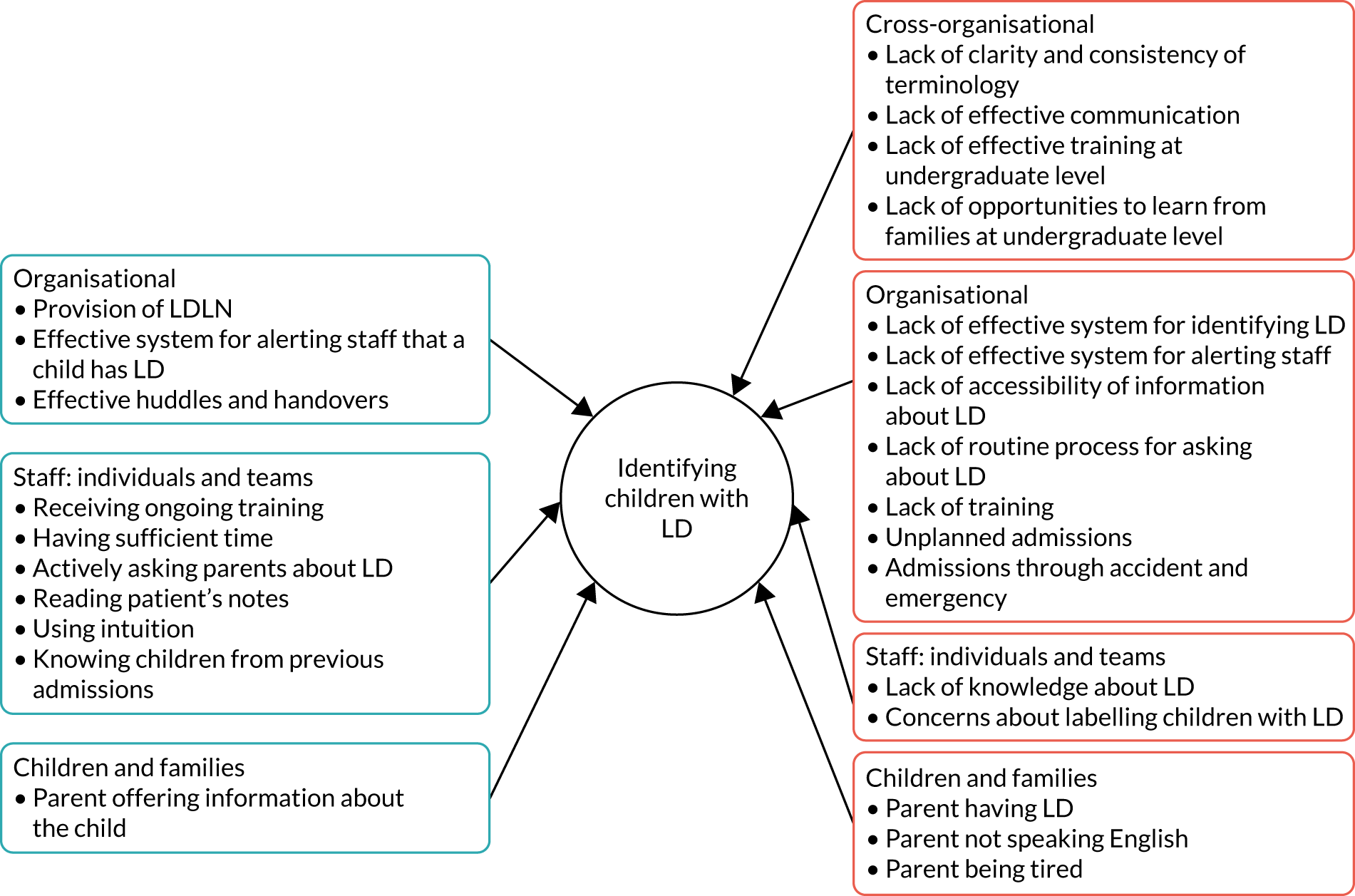

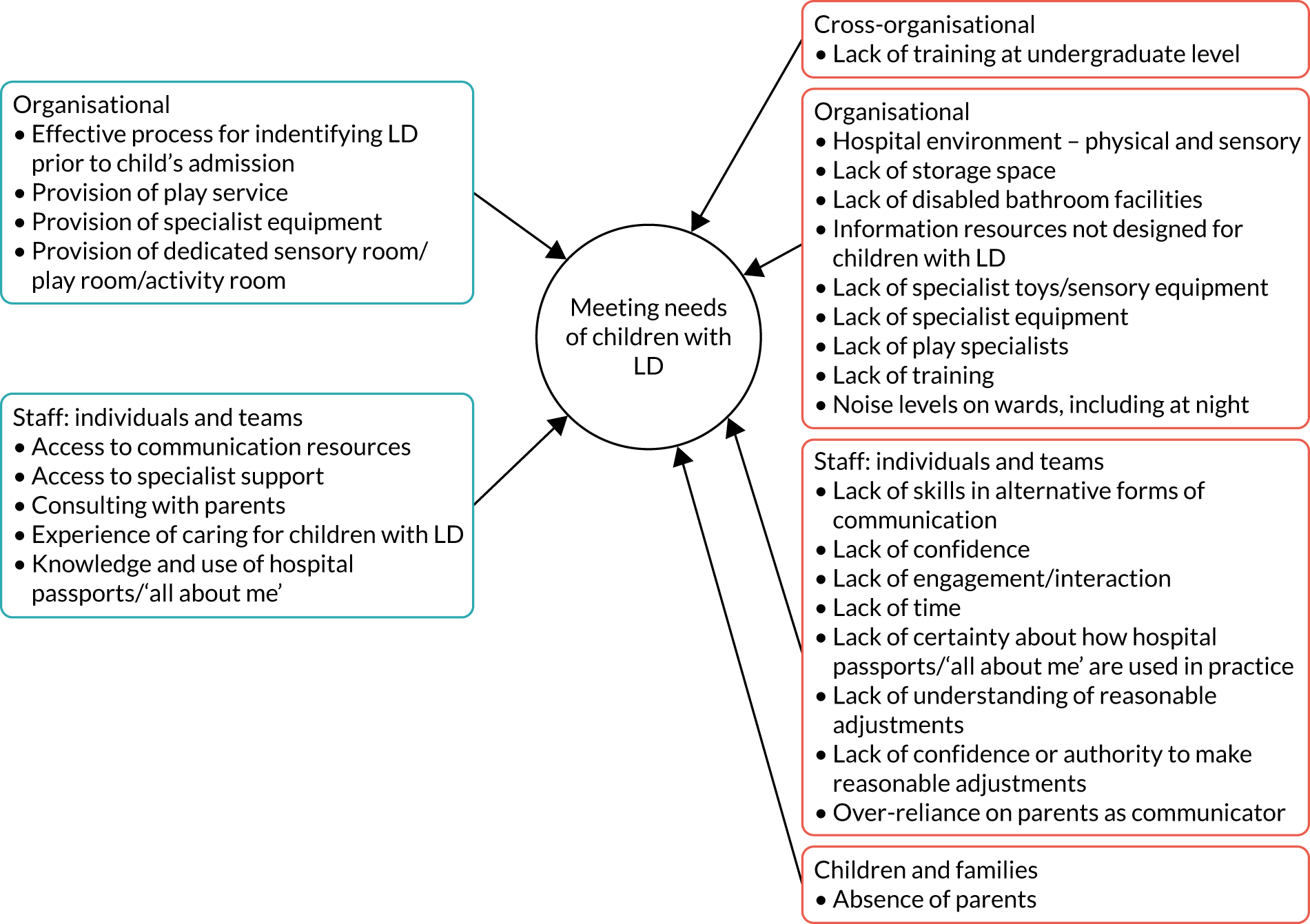

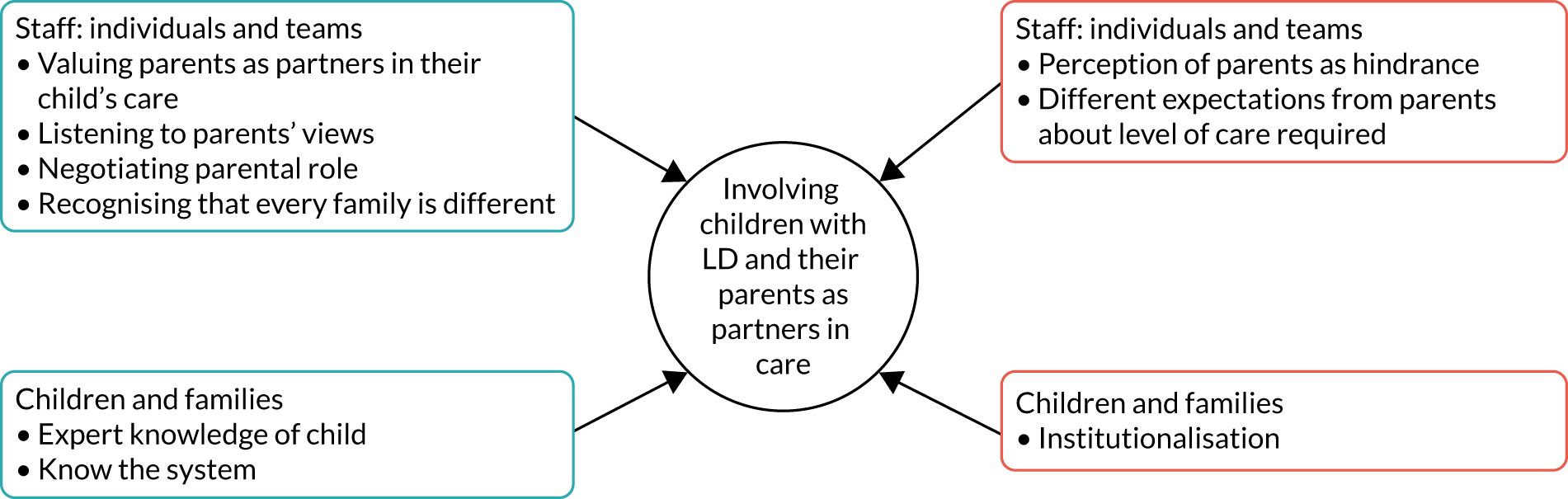

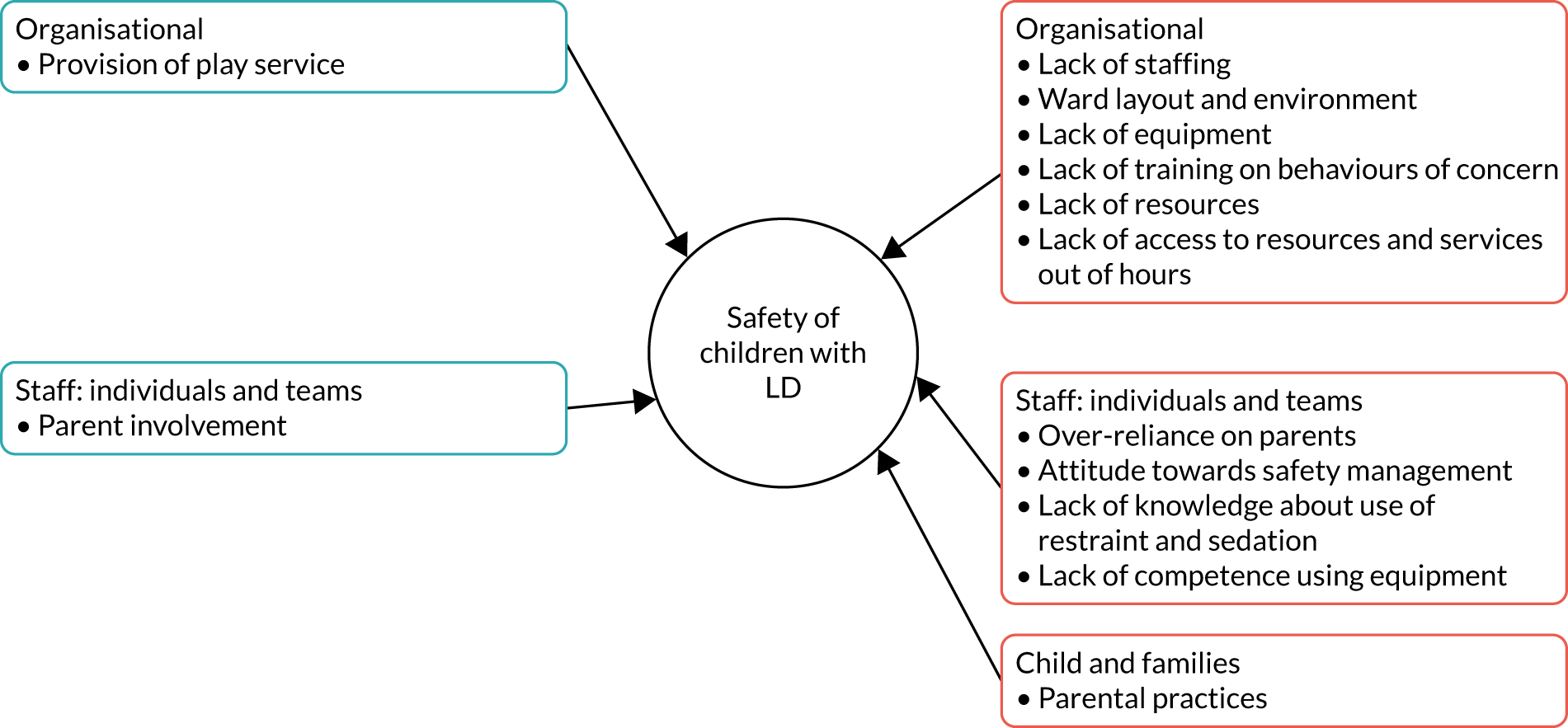

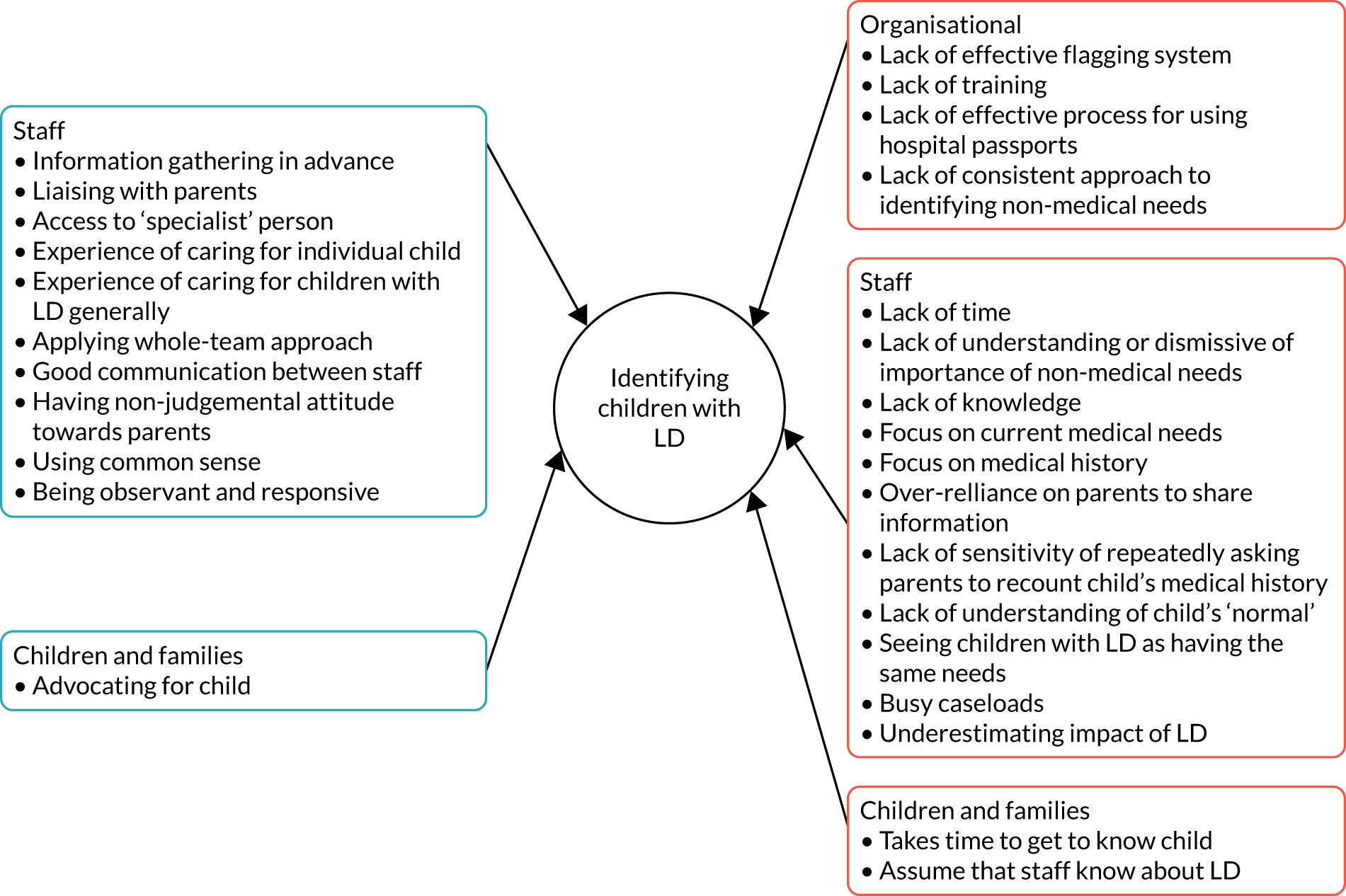

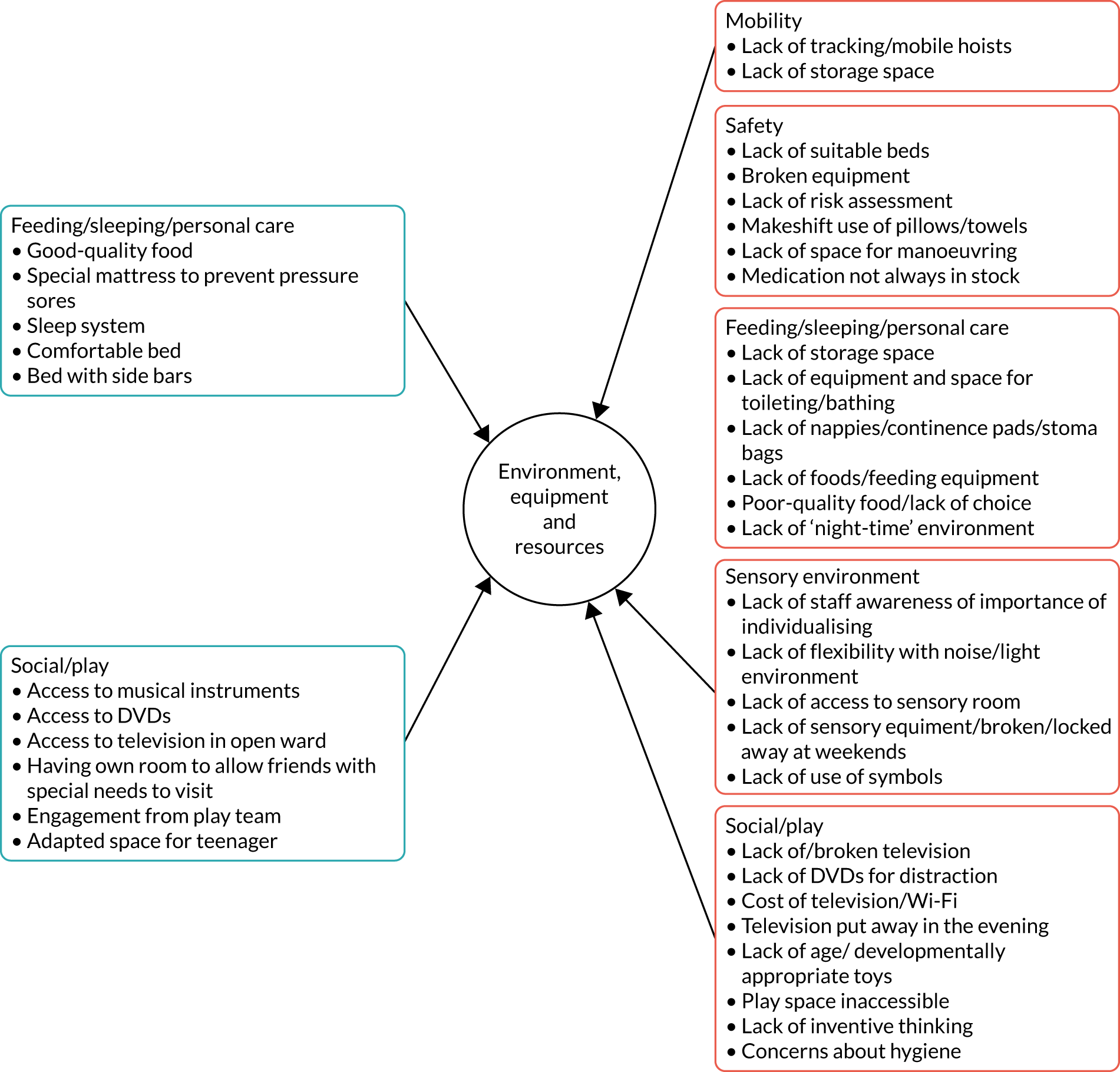

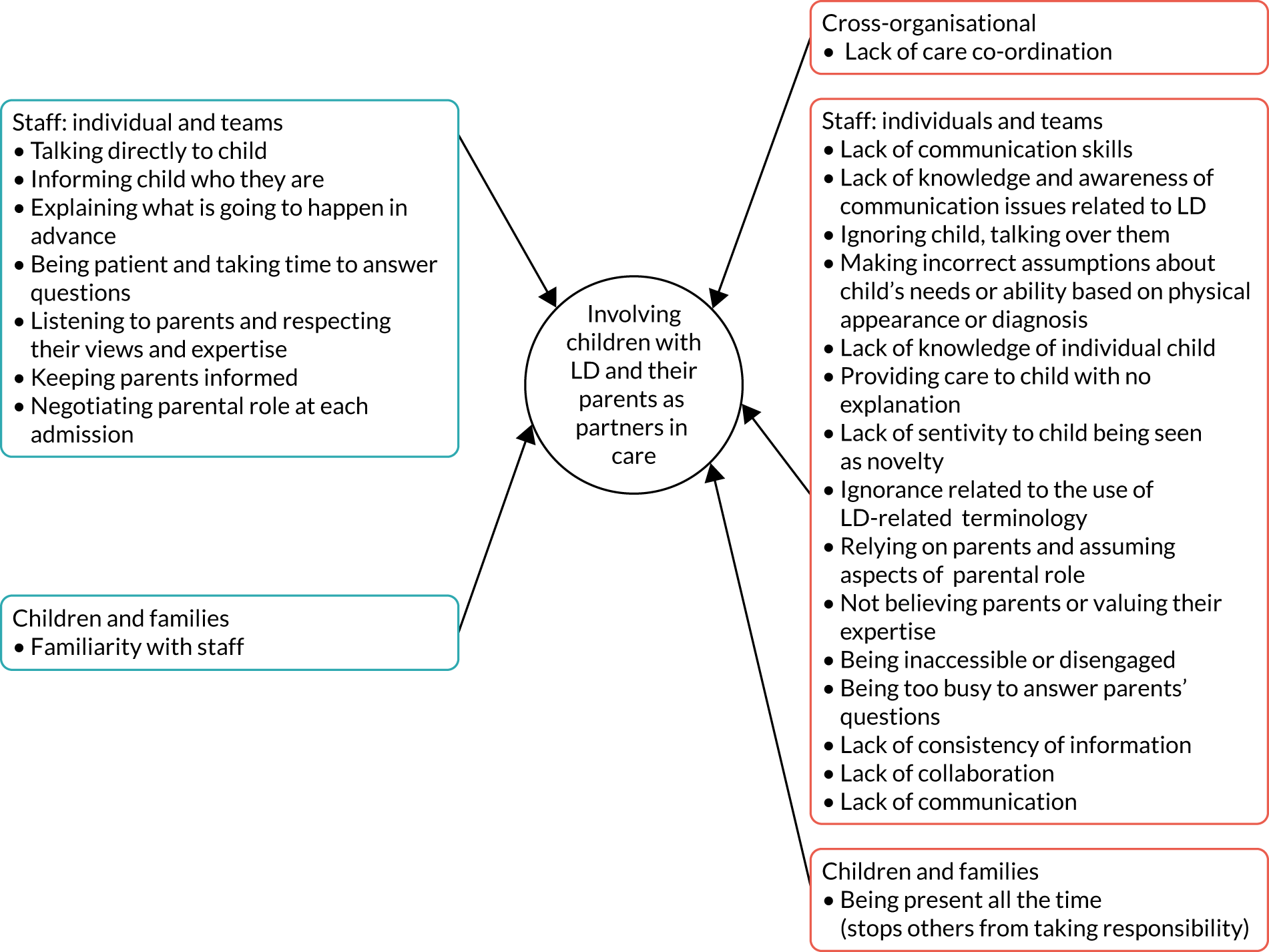

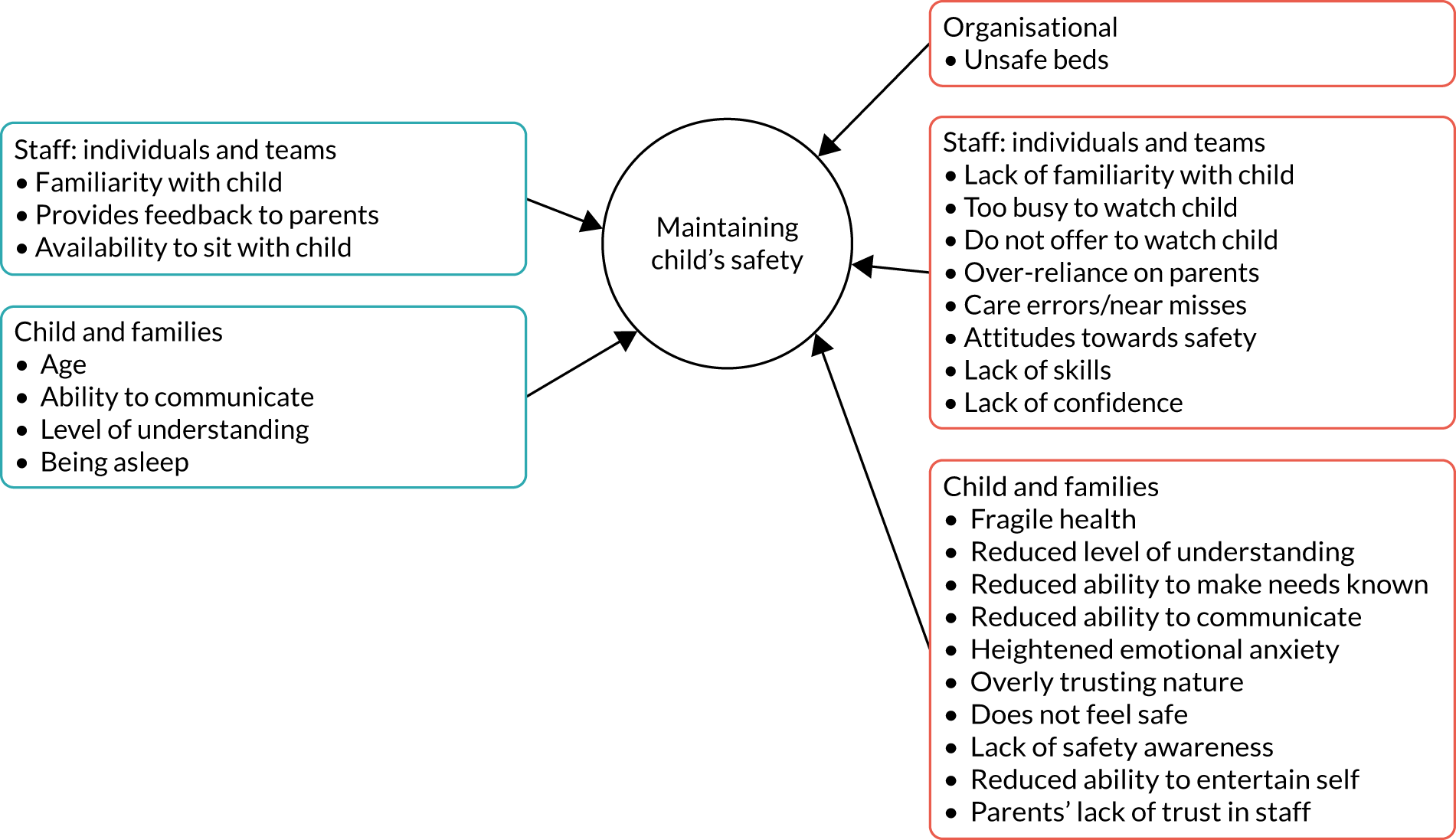

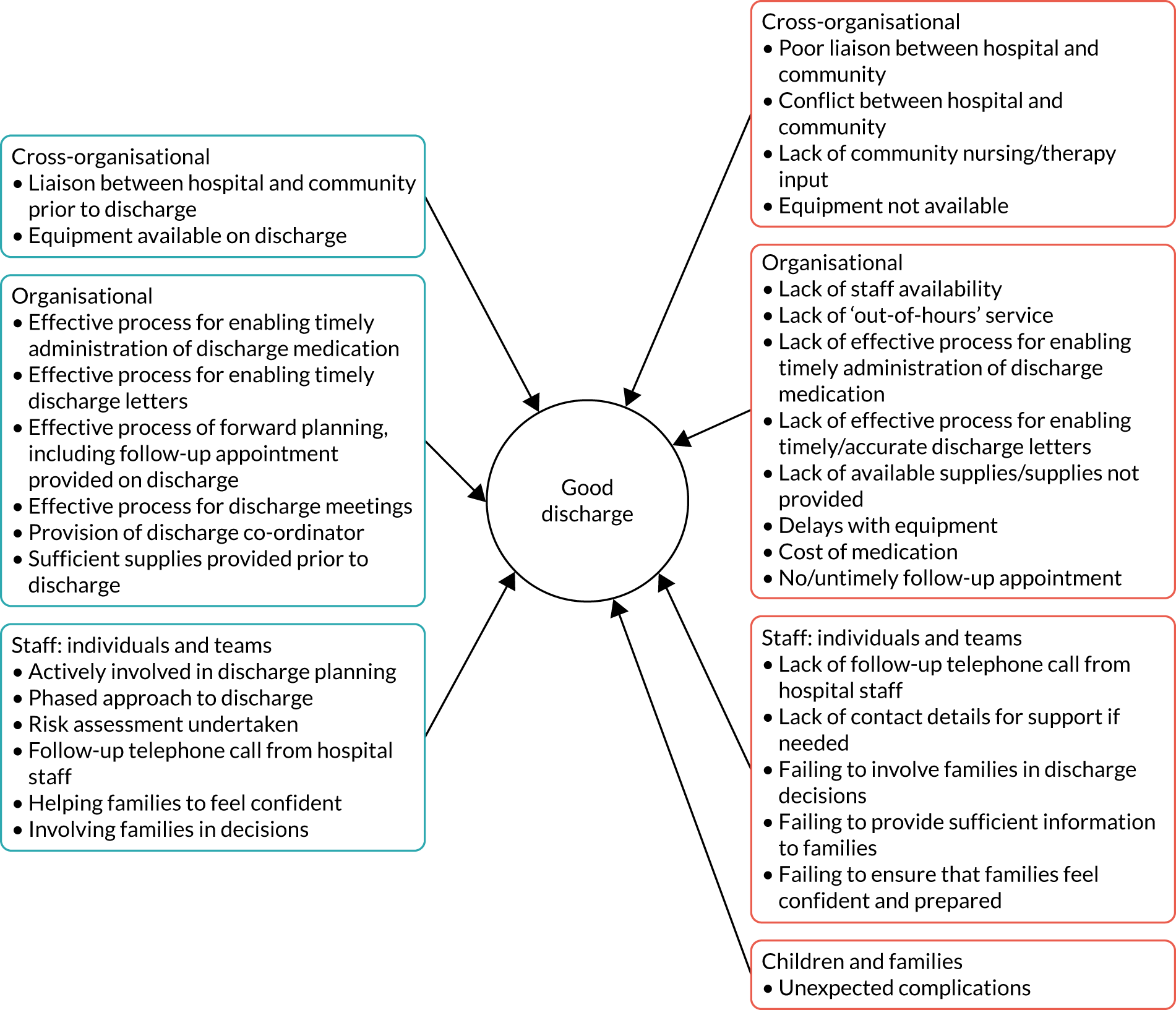

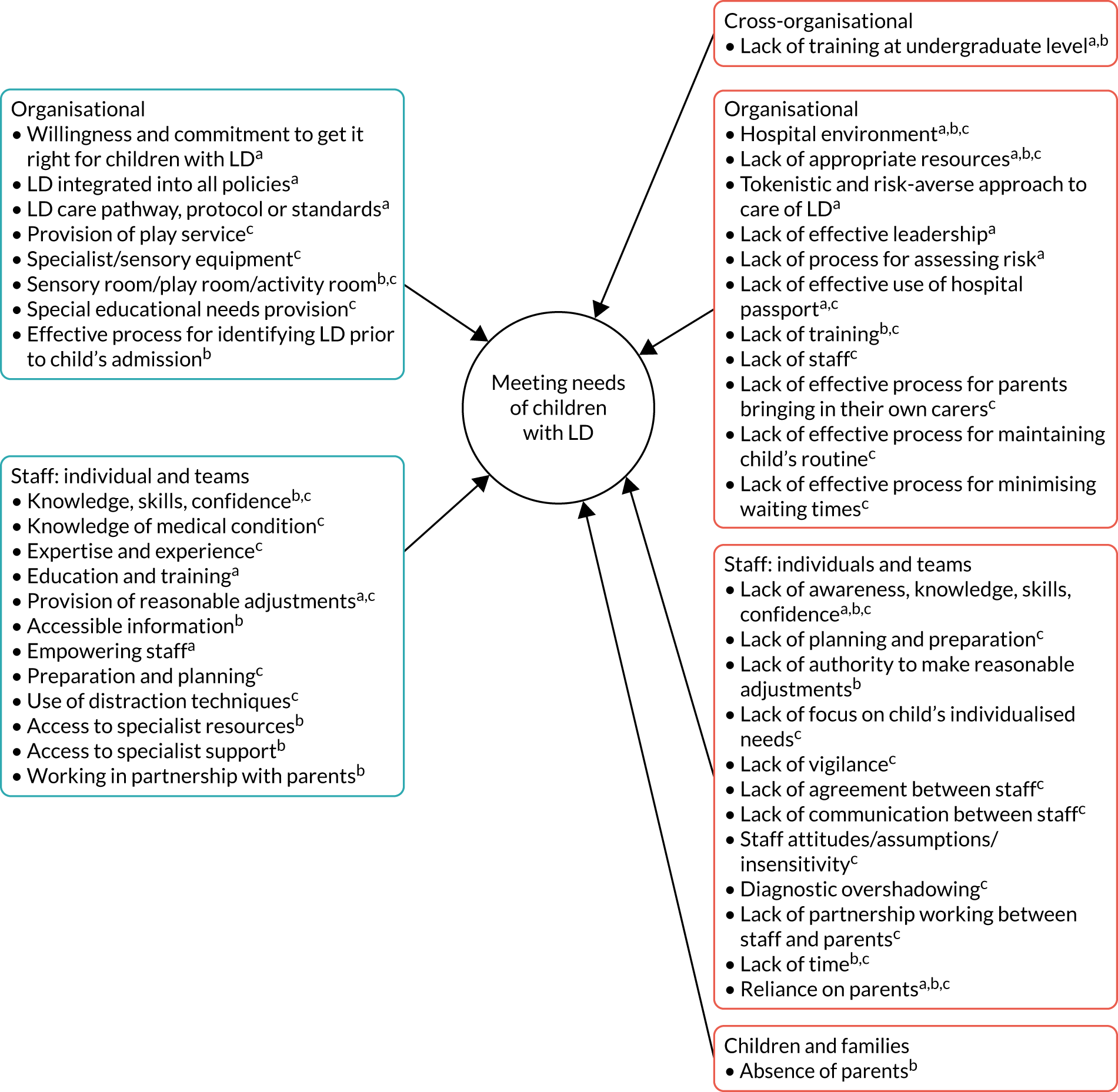

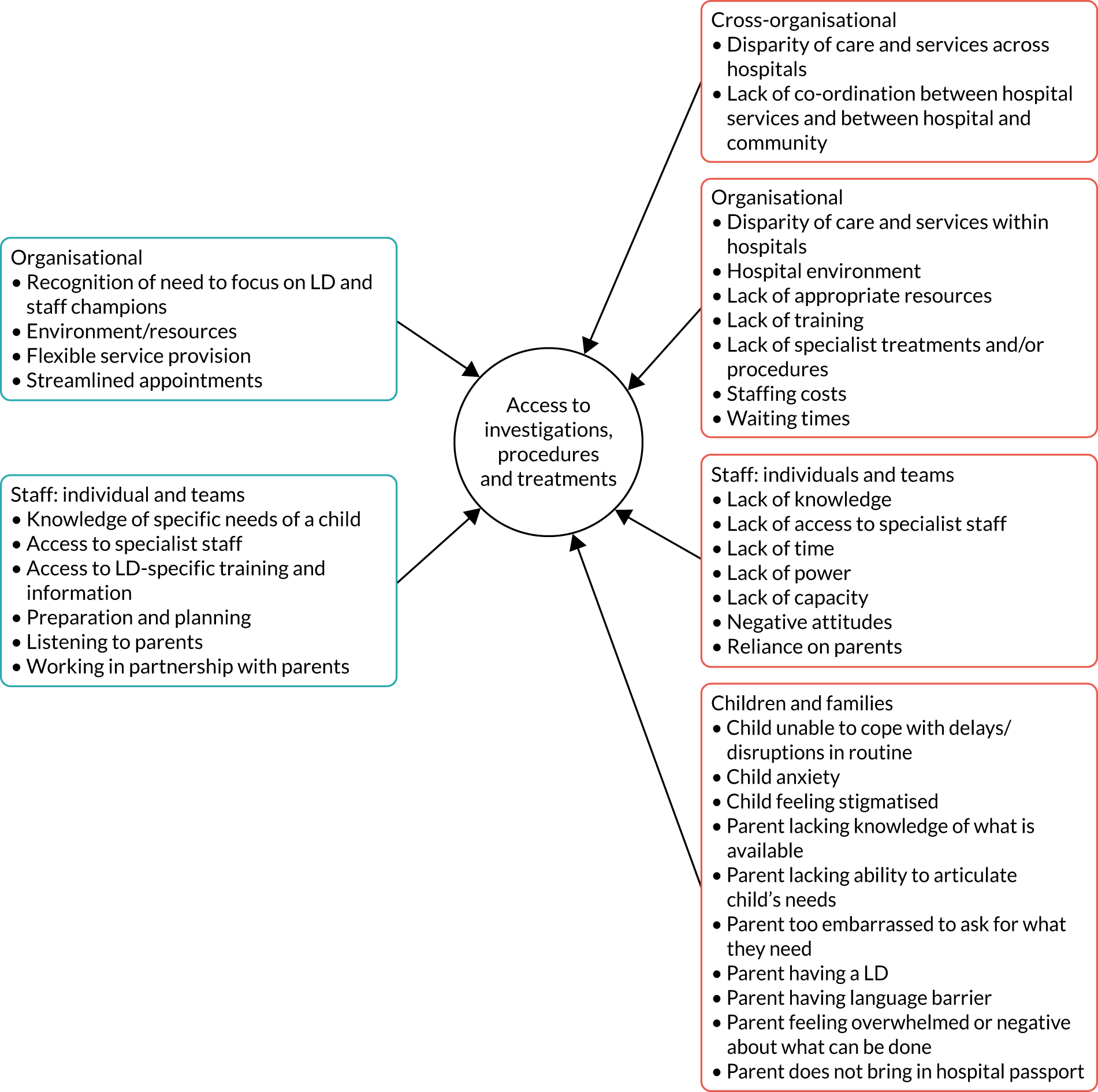

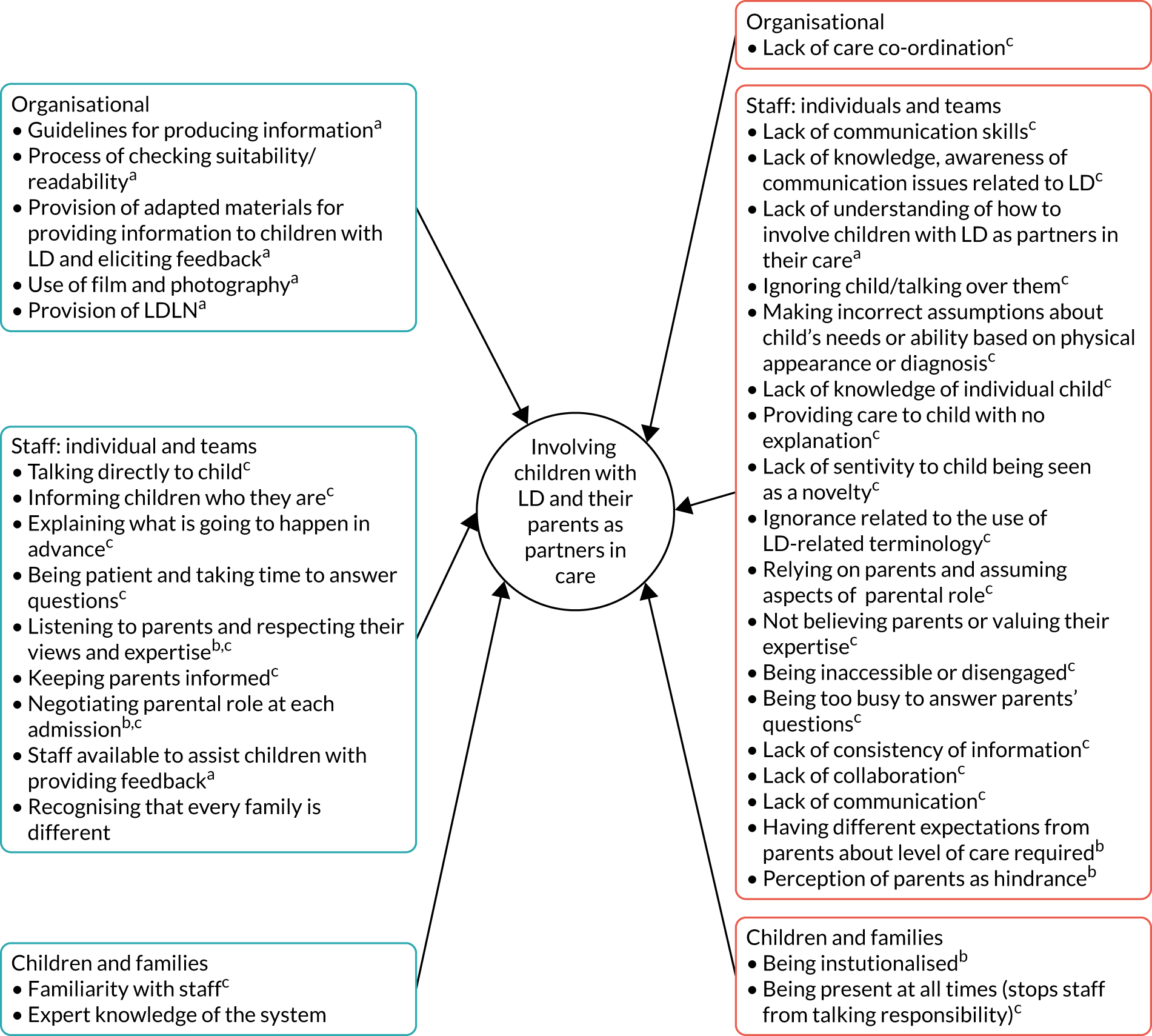

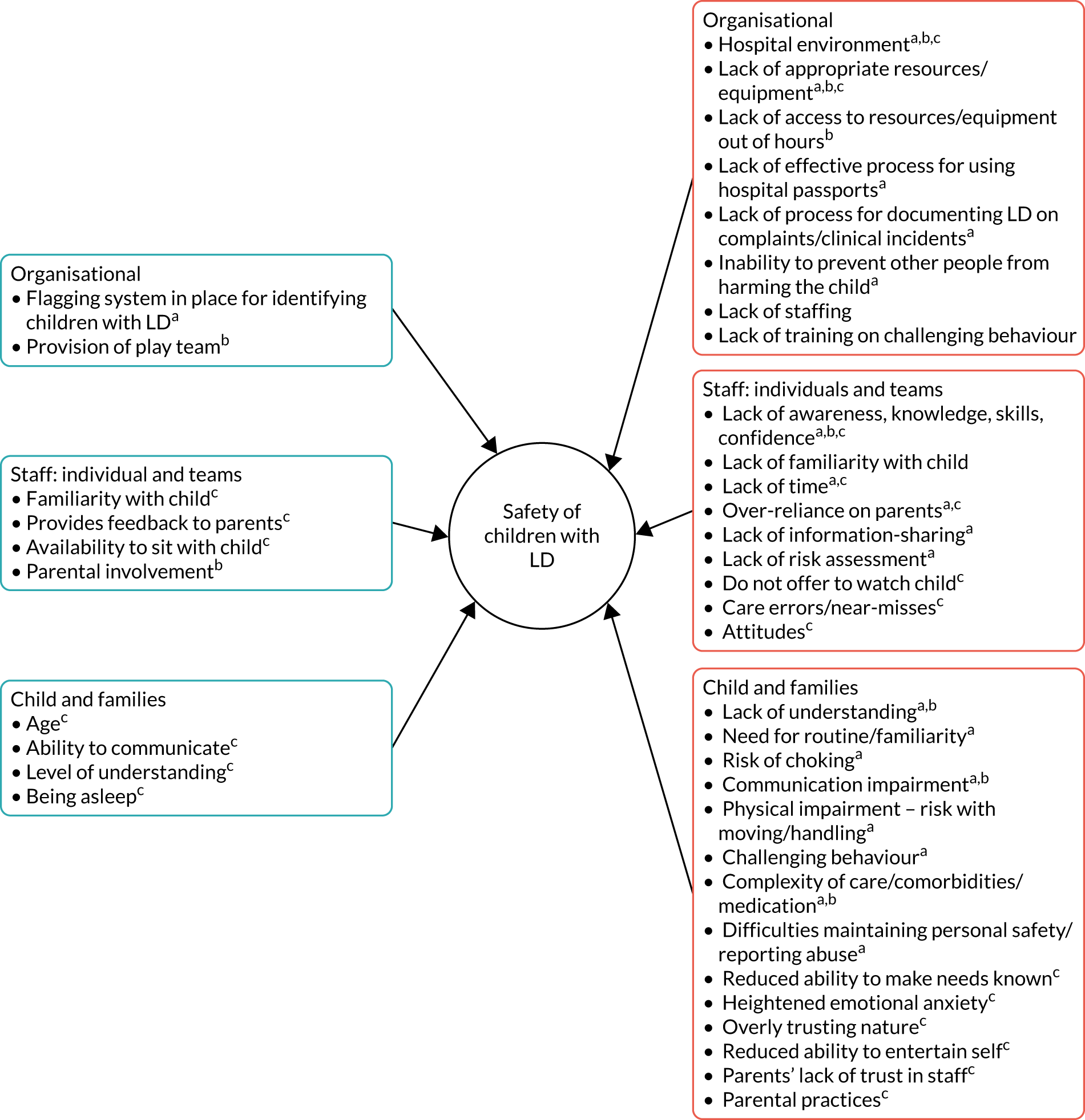

The results section comprises five chapters (see Chapters 5–10). The first three of these chapters focus on findings from staff, with data from the survey being used to identify whether or not staff perceive that inequality exists between children with and children without learning disability (LD) and their families (see Chapter 5). Findings from the organisational mapping exercise (see Chapter 6) and staff interviews (see Chapter 7) highlight the cross-organisational, organisational and individual staff factors in NHS hospitals that facilitate and prevent such inequality. Chapters 8–10 focus on parents’ experiences of being in hospital with their child. The narrative of parents of children with LD is the focus of these chapters, but important comparisons will be drawn from the views and experiences of parents of children without LD. Chapter 11 focuses on findings from the parent and child survey about satisfaction with different aspects of the hospital experience. At the end of each chapter the barriers to and facilitators of inequality for children with LD and their families will be presented in a series of diagrams related to each research question. Our aim is to incrementally build a comprehensive picture of what factors are key to ensuring equality.

Section 4

In the synthesis and discussion chapter (see Chapter 10), we bring the data together and generate a single diagram of barriers and facilitators for each research question (RQ), showing where staff and families overlap or differ in their thinking. Chapter 11 concludes with implications for practice and research.

Section 1 Introduction

Chapter 1 Background to the study

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Oulton et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Despite comprehensive evidence of health inequalities for adults with LD, including poor practice, discrimination and abuse in hospitals,2–5 to our knowledge there has yet to be a comprehensive review of how well hospital services meet the needs of children and young people (hereafter referred to as children) with LD and their families. A major uncertainty is when the inequalities known to exist for adults with LD start to emerge. Limited qualitative evidence of parental dissatisfaction with the quality, safety and accessibility of hospital care for children with LD exists (see Chapter 3). However, the extent to which these parents’ experiences differ from those of parents of children without LD is not known. Moreover, reports of the views and experiences of children with LD are almost non-existent in the literature.

This study set out to compare how services are delivered to, and experienced by, children with long-term conditions, with and without LD, and their families, to see what inequalities exist, for whom, why and under what circumstances. The cross-organisational, organisational and individual factors in NHS hospitals that facilitate or prevent children with LD and their families receiving equal access to high-quality care and services were explored. Our aim was to generate examples of effective, replicable good practice.

Definition and prevalence

A long-term condition is defined as a health condition that requires ongoing management over a period of years. 6 About one in seven young people (15%) aged 11–15 years in the UK reports that they have been diagnosed with a long-term medical condition. The more common conditions that affect children and young people include diabetes, asthma, epilepsy, severe allergies and anaphylaxis. Among those with a long-term condition, approximately 28% require medical follow-up, of whom approximately 6% have a disability. A proportion of these children will also have a LD, which is a neurodevelopment condition that covers a wide spectrum of impairments; various definitions are applied in the UK and internationally. In the White Paper Valuing People,7 the Department of Health and Social Care states that LD includes the presence of:

-

a significantly reduced ability to understand new or complex information or to learn new skills [impaired intelligence; intelligence quotient (IQ) of < 70], with

-

a reduced ability to cope independently (impaired social functioning).

These impairments start before adulthood and have a lasting effect on development.

Although IQ has historically been the defining measurement of LD, it is now recognised that a low IQ is not, in itself, a sufficient reason for deciding that an individual should be provided with additional health and support. This message was echoed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5),8 in which the term ‘intellectual disability’ (commonly used to describe LD internationally) replaced ‘mental retardation’ and IQ test scores were removed from the diagnostic criteria to prevent these being overemphasised in terms of a person’s overall ability.

The definition includes children with autism who also have LD, but it does not include those who have specific learning difficulties that may impair educational attainment, such as dyspraxia or dyslexia, but who are within the average range of intelligence or those with developmental delay who are late in reaching some or all of their developmental milestones. It is also important to distinguish children with LD from those with neurodiversity, who are of average or above-average intelligence.

Causes of LD can be genetic, or due to prenatal, perinatal and postnatal environmental factors. 9 There is no definitive record of the number of people with LD in England, but the estimated prevalence of LD in children and young people is 2.5%. 10 It is widely acknowledged that the numbers of those with severe intellectual impairment and multiple/complex long-term problems will continue to rise by 1% each year. 11

Health needs, inequality and inequity

In terms of their health, it is widely reported that disabled children are a vulnerable population12 whose care needs are significantly greater than those of other children. 13 However, accurate information about the prevalence of some impairments and health conditions in children with LD is limited, possibly because the population is heterogeneous, the terminology used varies and the main focus of recent efforts to reduce health inequalities related to LD has been adult care.

Much of the available evidence related to children comes from work carried out by Emerson et al. , including a review of the UK literature on the health inequalities experienced by children and young people with intellectual disabilities. 14 Emerson and Hatton15,16 reported that ‘the risk of children being reported by their main carer (usually their mother) to have fair/poor general health is 2.5–4.5 times as great for children with learning disabilities as for other children’, a finding only partially accounted for by differences in socioeconomic status. 17 In addition, children with LD are almost twice as likely to report three or more health problems as children without LD. 16 More recently, a ‘disabilities terminology set’ was developed and used to quantify the multifaceted needs of disabled children and their families in a district disability clinic population. 13 Compared with children without LD, children with LD were found to have significantly more needs overall, including more health conditions, health technology dependencies and family-reported issues, and were more likely to need round-the-clock care.

As well as having intellectual impairment, a large proportion of children with LD will have sensory impairments, such as vision or hearing impairment,18 and/or communication difficulties. 19 They also have higher rates of all types of incontinence, sleep disorders, obesity and epilepsy14 than children without LD. The prevalence of epilepsy among people with LD is at least 20 times higher than among people without LD, and the seizures they experience are commonly resistant to treatment. 20–23

In terms of mental health, children with LD are at significantly increased risk of certain types of psychiatric disorder (prevalence of 39%) compared with children without LD (prevalence of 8%). 24 Some children with LD also have autism spectrum disorders, although estimates of prevalence of these vary considerably. 14 There has also been a reported threefold increase in the risk of behaviours that challenge in children with LD compared with typically developing children,25 a major contributing factor being the existence of a communication impairment that may limit the child’s ability to express frustrations or explain any underlying emotional/physical distress or other external factors.

Children with disabilities experience more frequent and lengthier hospital admissions than children without disabilities,26 which has an impact on school attendance. 17 The ability for children with LD of all ages to understand information about hospital care and treatment may be limited; they may not be able to communicate their needs verbally and may need additional support with all aspects of hospital life. Although many children will find it hard to cope emotionally when they are in an unfamiliar hospital environment, those with LD who display behaviours that challenge27 may find it particularly difficult.

Policy

The publication of Death by Indifference,2 about six people with LD who were seen to have died in hospital unnecessarily, triggered an independent inquiry into access to health care for adults with LD, which revealed significant system failures and less favourable treatment of these patients than those without LD, resulting in prolonged suffering and inappropriate care. The report of this inquiry, Healthcare for All,3 identified the invisibility of people with LD within health services, with a lack of priority given to identifying their particular health needs. A lack of training, combined with ignorance and fear, were recognised as compounding negative attitudes and values held about people with LD and their carers. Furthermore, these were notable factors in failing to deliver equal treatment and to people being treated respectfully and with dignity. 3 A need to strengthen the systems for assuring the equity and quality of health services for people with LD at all levels was identified. The limited direct reference to children with LD in the report presents a mixed picture. Services were praised for ‘providing all-round care’, yet access to general health care for children with LD was reported as being ‘as problematic as it appears to be for adults’.

The resulting Confidential Inquiry into Premature Deaths of People with Learning Disabilities (CIPOLD)4 found that people with LD die, on average, 16 years earlier than people in the general population. Furthermore, it emerged that ‘more people with LD died from causes that were potentially amenable to change by good quality healthcare’. 4 All aspects of care provision, planning, co-ordination and documentation were found to be significantly poorer for people with LD.

NHS England subsequently commissioned the continuing Learning Disabilities Mortality Review (LeDeR)5 programme to monitor deaths among people with LD.

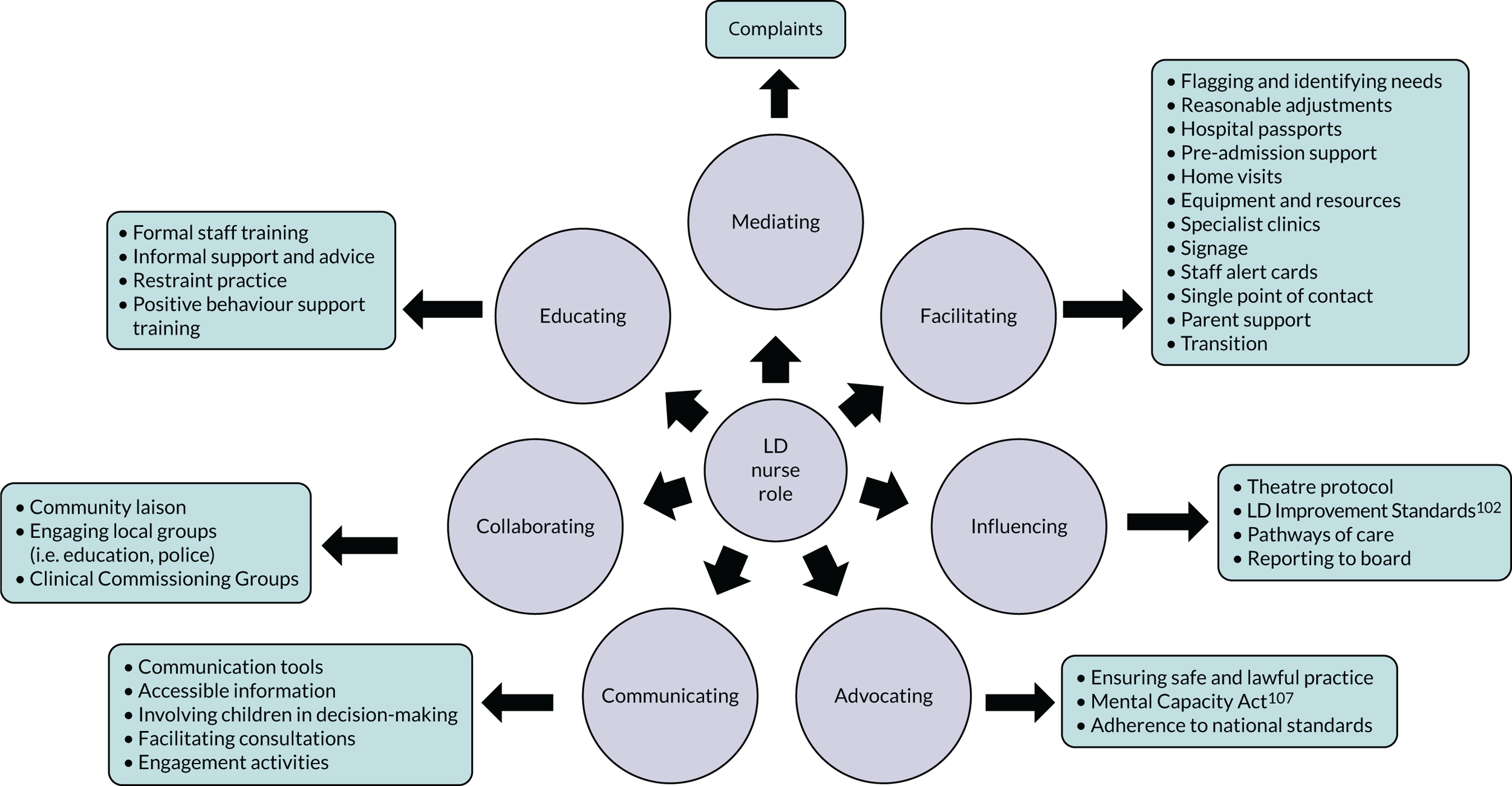

In 2014, the Care Quality Commission introduced a new regulation and inspection process for health and social care services in England, which assesses whether or not services are safe, effective, caring, responsive and well led. Care Quality Commission best-practice guidelines now advocate that ‘all children’s units to have access to a senior learning disability nurse who can provide information, advice and support to health care staff involved in the care of such children and who can help manage difficult situations’. 28

Little evidence exists of the extent of LD nurse provision in children’s hospitals or the nature and impact of this role. A recent NHS benchmarking exercise29 aimed at providing a ‘broad assessment of the state of NHS learning disability services’ failed to include data concerning children’s inpatient LD service provision. As stated in the Royal College of Nursing30 position statement on the role of the LD nurse, ‘National work needs to be undertaken by each UK country as a matter of priority to profile the existing learning disability nursing workforce and identify future requirements’ (reproduced with permission from the Royal College of Nursing). 30 A Department of Health and Social Care-commissioned review by the National Council for Disabled Children31 revealed a number of staffing issues related to the care of children and young people with complex needs and behaviour that challenges involving mental health problems and LD and/or autism. A key finding was the lack of recognition and value placed on the specific skills needed to work with these children, with no professional group identifying themselves as being wholly trained in one or more of their needs. Furthermore, specific issues surrounding the recruitment of nurses with LD education and training were identified, including the possibility that ‘it was only when they were on shift that care plans for this group were implemented’. A need to understand the gaps in staff skills in caring for these children and take necessary action was highlighted.

A key strength of our study is that is has been designed to generate evidence of the issues that affect all children with long-term conditions and those that are particular to children with LD. This evidence is needed to understand the context for making reasonable adjustments for children on the basis of their specific intellectual, emotional, social and physical needs, helping to ensure that resources and interventions that promote equality are better targeted to those who need them, when they need them.

Chapter 2 Study aims and theoretical framework

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Oulton et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Study aims

Primary aim

To identify the cross-organisational, organisational and individual factors in NHS hospitals that facilitate or prevent children with LD and their families receiving equal access to high-quality care and services.

Secondary aim

To develop guidance for NHS trusts about the implementation of successful and effective measures to promote equal access for children with LD and their families.

Research questions

From the perspectives of families and clinical staff

-

Do children with and children without LD and their families have equal access to high-quality hospital care that meets their particular needs?

-

Do children with and children without LD, assisted by their families, have equal access to hospital appointments, investigations and treatments?

-

Are children with and children without LD and their families equally involved as active partners in their treatment, care and services?

-

Are children with and children without LD and their families equally satisfied with their hospital experience?

-

Are safety concerns for children with and children without LD the same?

-

What are the examples of effective, replicable good practice for facilitating equal access to high-quality care and services for children with LD and their families at the study sites?

-

What indicators from the data and the literature suggest that the findings may be generalisable to other children with long-term conditions in the hospital setting?

Theoretical framework

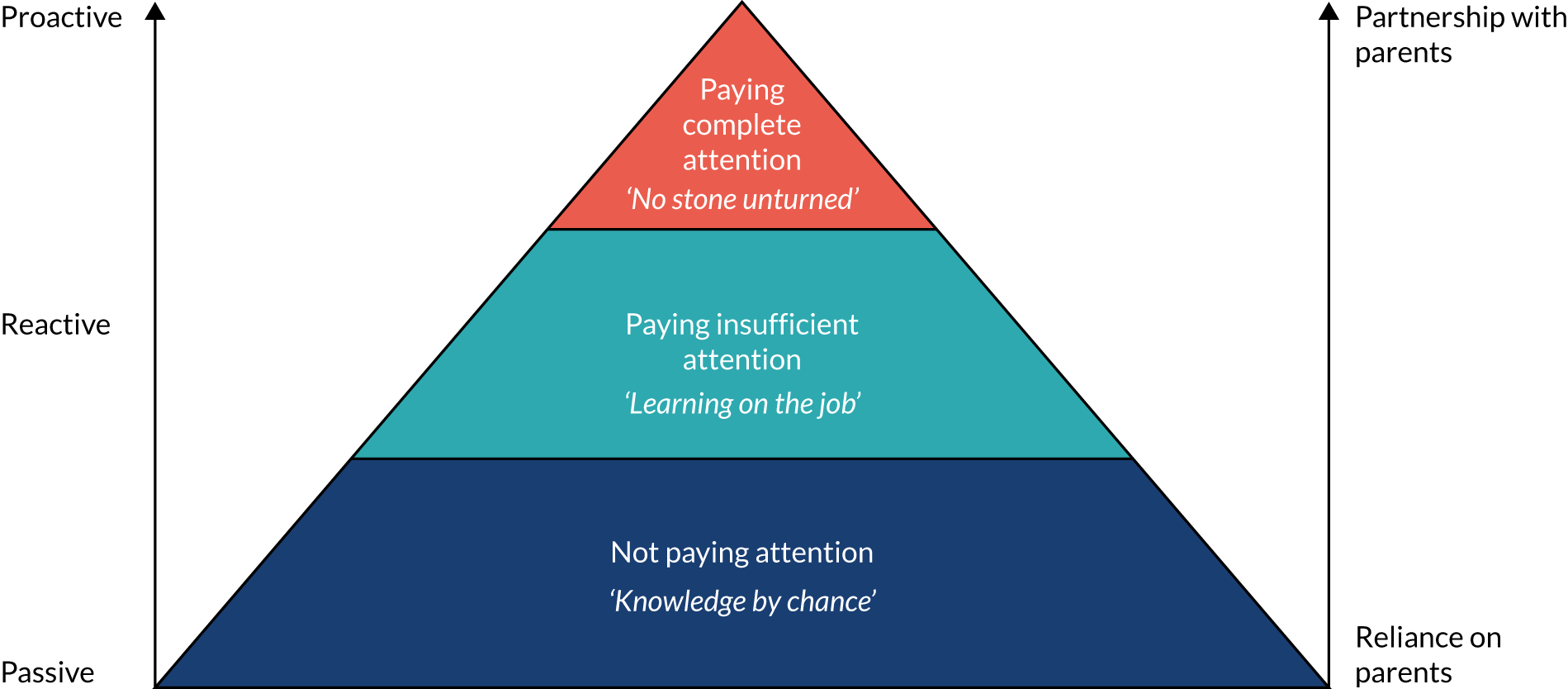

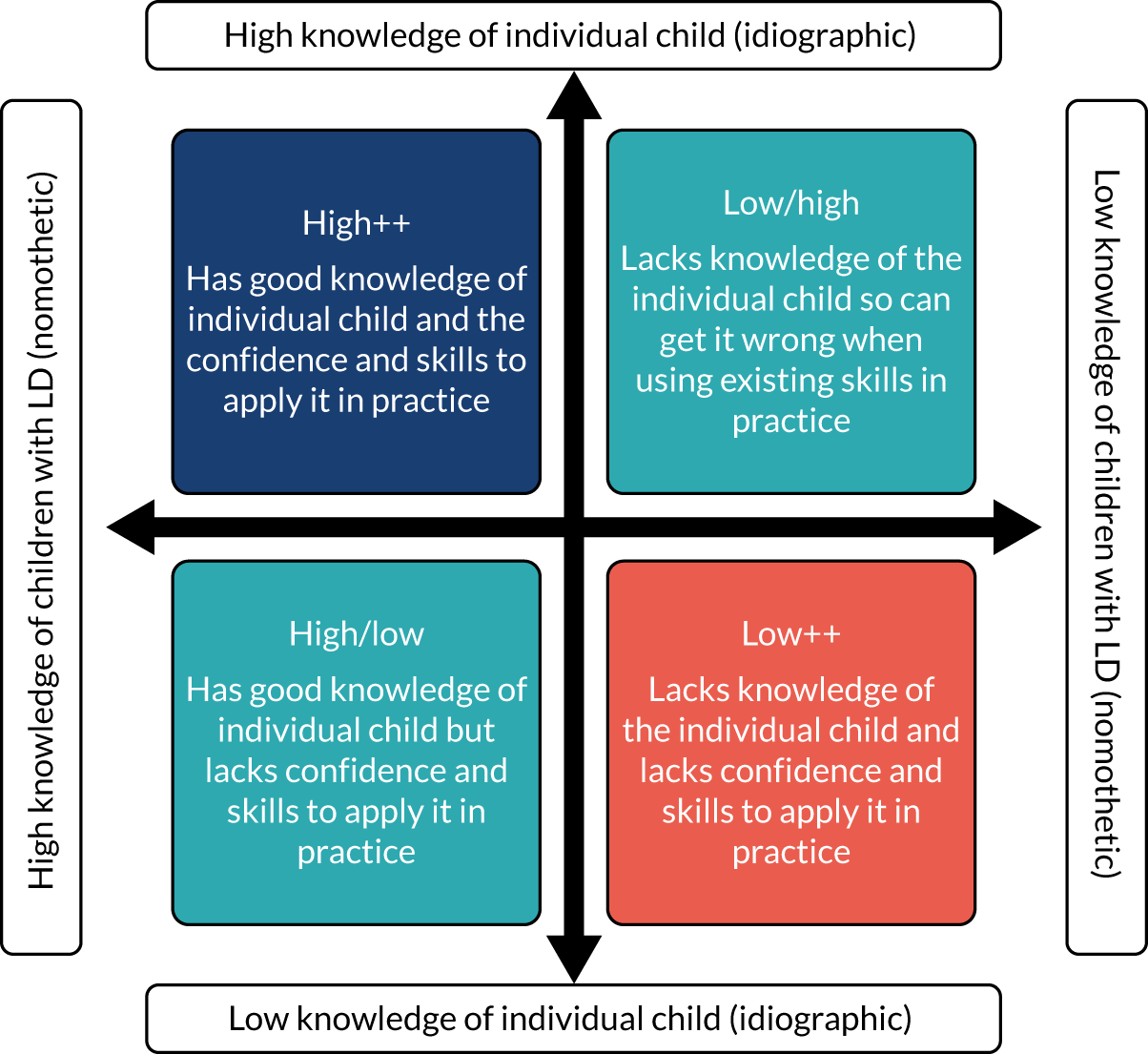

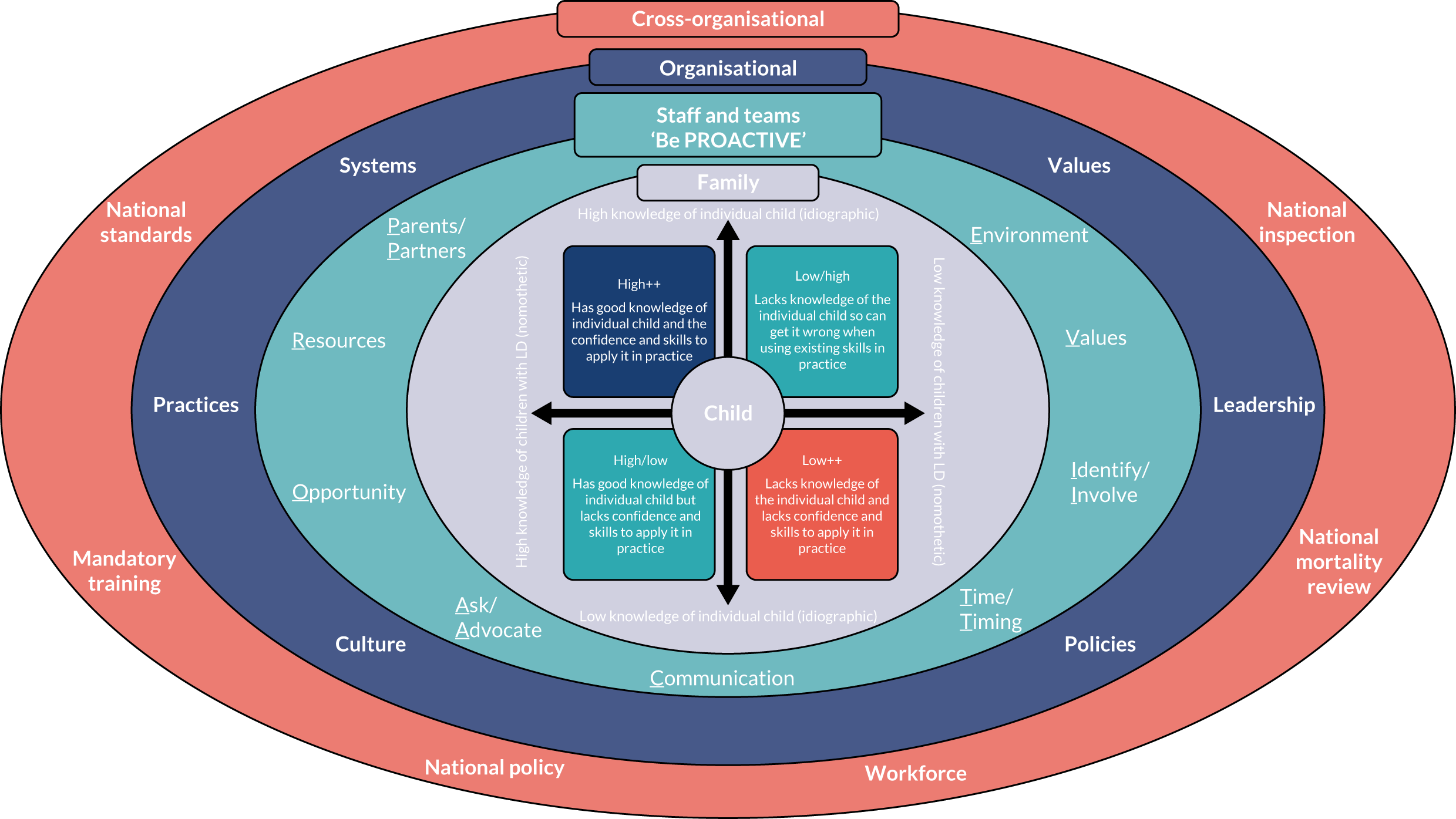

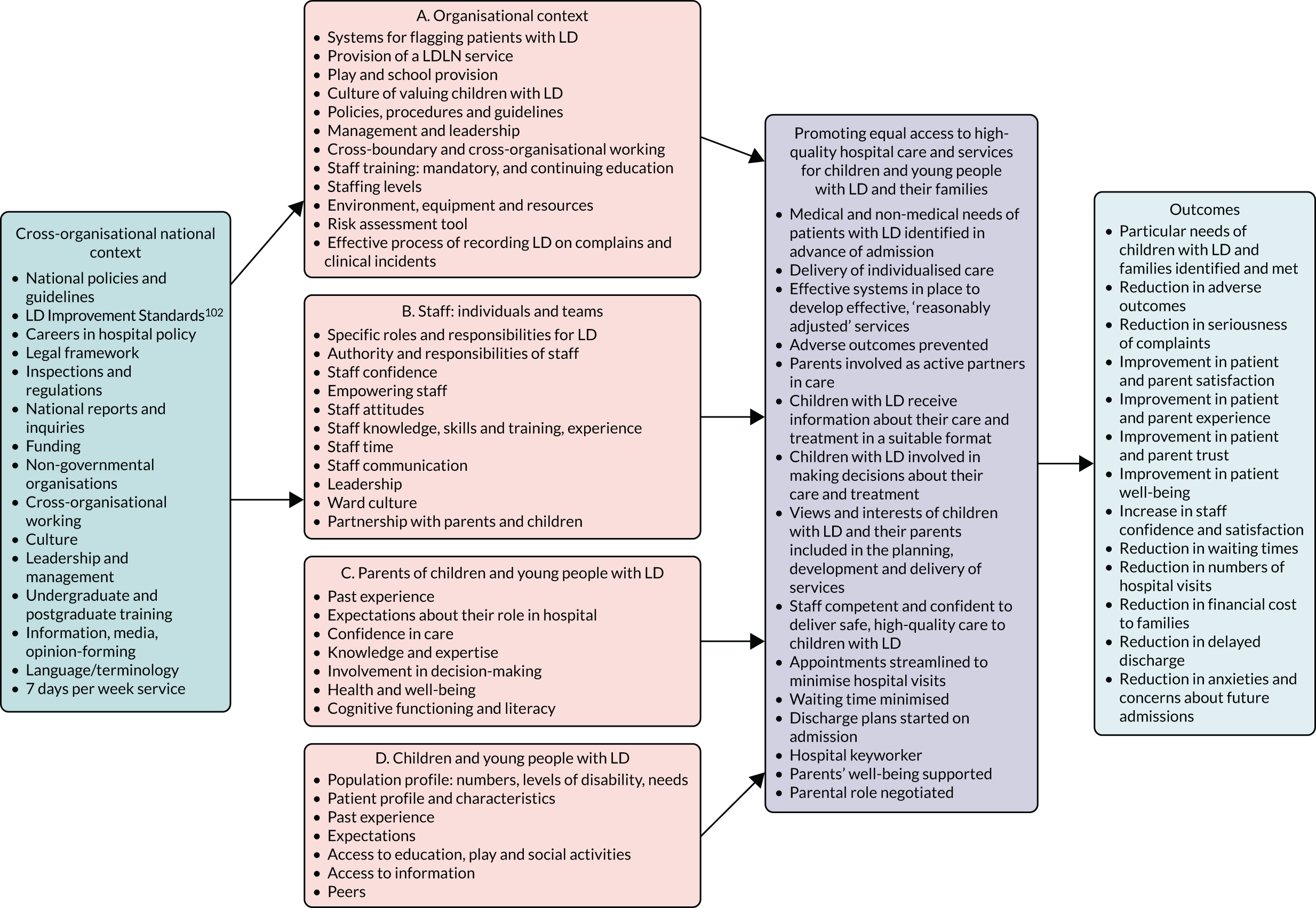

We took a systematic approach to an empirical identification of the factors that affect access to high-quality hospital care for children with LD and their families. Building on the work of Tuffrey-Wijne et al. ,32 we devised a provisional theoretical framework for understanding the range of factors at the cross-organisational, organisational and individual levels that might have an impact on the delivery of hospital care to children with LD and their families (Figure 1). This framework was informed by a synthesis of existing policy and literature (see Report Supplementary Material 1) and the wide-ranging expertise and experience of the multidisciplinary research team. Organisational and individual domains of the theoretical framework are indicated in boxes A, B, C and D (see Figure 1). Each box contains a number of factors within each domain that might function as barriers to, or facilitators of, promoting equal access to high-quality hospital care for children with LD and their families in NHS hospitals. Included are outcomes that might be associated with effective measures for promoting equal access. Having tested and refined the theoretical framework throughout the study, it is re-presented in Chapter 12 as an empirical framework for promoting equal access to high-quality hospital care for children with LD and their families.

FIGURE 1.

Theoretical framework. LDLN, learning disabilities liaison nurse.

Chapter 3 Learning from the literature

The number of children with long-term conditions, with and without LD, who require complex care is growing, resulting in the increased use of health-care resources as these children spend prolonged periods of time in hospital for both acute and planned admissions and for both medical and surgical care. The quality of the hospital stay and the extent to which hospital services meet the needs of all children have been studied for some time; the body of literature is expansive. Inequalities have been highlighted but not examined in any detail, particularly in relation to children with LD. The impact of a hospital environment on these populations has rarely been considered in the context of a shared narrative. Rather, studies tend to concentrate on the views of particular stakeholders, such as children, parents or staff, and not on how services are delivered within and across particular hospital settings. For the purposes of this report, we present relevant learning from the literature, focusing predominantly on a number of recently published systematic and narrative reviews.

Adults with learning disability

The majority of studies that do focus on the hospital care of patients with LD relate to the care of adults. Although it is not within the remit of this report to present a review of this literature, three major pieces of work are of particular relevance: a systematic review of hospital experiences of people with LD in general acute hospitals,33 a narrative review of acute care nurses’ experiences of nursing patients with LD,34 and a national mixed-methods study35 of the factors preventing the implementation of strategies to promote a safer environment for patients with LD in English hospitals.

The systematic review of 16 studies of the hospital experiences of people with LD32 revealed seven overarching themes ‘related largely to failures of hospitals and staff to meet patient needs’. The key factors contributing to such failures were staff attitudes and their limited knowledge and skills concerning LD, and a failure at the systems level to make necessary adjustments, resulting in carers being relied on both for care and to advocate for appropriate treatment. Facilitators of care were exceptions rather than common experiences. The narrative review of the experiences of acute care nurses34 similarly found that nurses felt underprepared when caring for adult patients with LD, experienced challenges communicating with them and had ambiguous expectations of paid and unpaid caregivers.

There was also an overlap in findings from the large national study,35 which revealed the main barriers to better and safer hospital care for people with LD to be (1) the invisibility of patients with LD in hospitals, (2) poor staff understanding, (3) a lack of consistent and effective carer involvement and staff misunderstanding of the carer role, and (4) a lack of clear lines of responsibility and accountability. The provision of a learning disability liaison nurse with authority to change practice and the support of senior management were found to be the main enablers of safe care, along with ward managers who facilitated a positive ward culture and ensured the consistent implementation of reasonable adjustments.

Children with learning disability

Few studies focus specifically on the care of ‘children with LD’ in hospital. More often than not, researchers instead focus on particular impairments, such as communication, or specific diagnoses, such as cerebral palsy, without drawing out findings applicable to those with LD. Furthermore, studies related to disabled children or to those with special needs, complex or chronic health needs or who are medically fragile or technological-dependent can include mixed samples of children with and children without LD, or an unspecified sample, which makes it difficult to determine the findings that are relevant to those with LD.

Among those studies that are focused on the care of children with LD in hospital, very few directly include children with LD as participants. A structured review and synthesis of qualitative studies reporting on the experience of disabled children as inpatients36 concluded that their experience was ‘variable and not always optimal’. The main issue was related to communication, which emerged as a key factor in whether the child and family had a positive or a negative experience. Of particular relevance to children with LD was the finding that during outpatient appointments health professionals often talked to parents instead of the child, resulting in feelings of disempowerment,37 and that although parents valued the inclusion of their disabled child, they were worried that children with communication disorders would be misunderstood. 38 Importantly, only two of the eight studies included in this review focused specifically on the care of children with LD and, in these, only two individual children were interviewed. Of significance is that these two children, despite talking positively about nursing staff, were reported to be ‘less positive in general about their hospital stay than their parents’. 39 A recent ethnographic study, one of the few to include observation and interviews with hospitalised children with LD,40 revealed the importance of staff not making assumptions about the capabilities and wishes of these patients. Examples were provided of too much and too little information and involvement, with associated feelings of uncertainty or fear and worry. Observations of practice revealed how important the ‘little things’ are to these patients, such as particular objects or activities, and the anxiety that they can experience when these are not available. Maintaining their routine, keeping them occupied and avoiding waiting were also found to be central to these patients’ well-being in hospital.

Relationship between parents of children with learning disability and staff

The small body of evidence relating to the care of children with LD in hospital mostly focuses on parents’ views and relationships with staff. The importance of parents and professionals working in partnership during any child’s hospital admission is well documented in the context of family-centred care,41 but parents’ central connection to their child in a health-care system relationship is also essential. Family-centred care has been positioned as an approach that encompasses the whole family as the ‘unit of care’; however, recent work has suggested that some parents regard themselves as the ‘care recipient’,42 supporting other work that, in this ‘unit of care’, the child is lost. 43 We do not know what children think about this approach to care, but we do know that having parents nearby is central to their experience,44,45 reinforcing the need for a positive and trusting relationship between parents and hospital staff.

What do parents say?

Much of the existing evidence about the relationship that parents of children with LD have with hospital staff has been captured in a recent systematic review12 specifically about patient safety vulnerabilities in this population and a meta-narrative46 of the experiences of parents of children with LD in hospital. A key theme of the systematic review was the reliance staff had on parents being present to ‘supervise, protect and advocate for the care of their child’. 12 Furthermore, it was reported that the understanding of the individual needs of children with LD could be compromised by assumptions staff make about their behaviour, cognitive ability or experience of pain. It was concluded that ‘when healthcare workers understand and are responsive to children’s individual needs and their intellectual disability, they are better placed to adjust care delivery processes to improve care quality and safety’12 during children’s hospitalisation. The meta-narrative of parents’ experiences of children with LD in hospital46 revealed their sense of being ‘more than a parent’ during this time as a result of their monitoring, protecting and advocating role and feeling expected to take responsibility. They also experienced uncertainty in relation to staff roles and responsibilities, and whether staff had the capacity and knowledge to provide safe, high-quality care to their child. The importance of staff knowing the child and working in partnership with parents also emerged. Adding to these two reviews is a more recent paper reporting on the views of parents of hospitalised children with LD,47 which adds to our understanding of what working in partnerships with professionals means to them. A genuine partnership was characterised by seven key elements: preparation, accessibility, reliability, trust, negotiation, expertise and respect.

The findings from these reviews support the theory of devoted protection put forward by Oulton and Heyman48 in their exploratory study about parenting children with severe LD. They found that parents adopted a risk-averse approach to care across all settings, including in hospital, which meant that they felt complete, unbounded responsibility for their child’s health and well-being. This included never leaving the child alone with someone they did not trust completely; when parents did leave their child, the occurrence of any problems could destroy their trust and prevent them from doing this in the future. They expressed apprehension that the specialist knowledge they held about their child was lacking in others, anger at not being listened to, and concern that their dedicated commitment was unequalled. A feeling that professionals devalued both them and their child with LD was also reported. Wider descriptions of parenting roles and responsibilities for disabled children, not specific to hospital, are also relevant to understanding what it might mean for them to accompany their child into hospital, with parents feeling that asking for support is a sign of failure and inability to cope,49,50 being so overwhelmed that they neglect their own needs,51 wanting to relinquish their responsibility because they feel that they are being taken advantage of52 or becoming increasingly expert so that their sense of responsibility becomes self-perpetuating and invisible to others. 48,53,54

What do staff say?

Although staff views about the care of patients with LD are captured almost entirely in relation to adults, some recently published small-scale studies offer some understanding of what it is like for hospital staff to care for children with LD. One ethnographic study55 included interviews with 23 staff members across a range of professional groups working in a specialist children’s hospital and revealed the need for children with LD to receive individualised care based on staff gaining appropriate experience and training, identifying the population, focusing on the ‘little things’, creating a safe, familiar environment, and accessing and using appropriate resources. Parents were seen to play a central role. It emerged that a lack of staff experience, knowledge, confidence and communication about LD can mean that they rely on parents’ input rather than forming a true partnership with parents. The compartmentalisation of nurse training and the movement of medical staff from specialty to specialty were identified as barriers to these professional groups gaining a ‘true understanding’ of the holistic needs of children with LD. A lack of content on developmental disability in the undergraduate curriculum for both doctors and nurses56,57 has been expressed elsewhere. More recently, Lewis et al. 58 interviewed eight nurses working on an acute admission paediatric ward in a general hospital in Australia, who described that caring for children with LD was in some ways similar to caring for children without LD, in that the goals of keeping them happy and getting them well and back home to normality were the same. Medical diagnosis and treatment were reported to guide care irrespective of other factors. However, further evidence emerged of the need for increased vigilance and additional time to meet the needs of these patients and to keep them safe, as well as the importance of routine, familiarity and working in partnership with parents to negotiate care responsibilities.

Children and young people without learning disability and their parents

There has been an increase in research conducted with children without LD, including those with long-term conditions, to understand the hospital experience from their perspective. This large body of evidence has shifted in focus from a predominantly parental to a child perspective, with an emphasis on the use of qualitative research. Children and their parents may often disagree on what the child’s experience in the hospital is really like,59 describing differing perceptions on issues such as safety, decision-making and lack of privacy. 60–62 Children’s descriptions can be captured using themes from Coyne and Conlon:61 fears about the ward environment and hospital, investigations and treatments, being alone, and what might happen. 63 What helps are people: their characteristics, activities, environment and outcome. 60

Parents describing their experiences of care have prioritised important hospital processes, such as effective clinical care, efficiency, safety and security, timeliness, and patient- and family-centred care. 64,65 Open communication and a willingness to share information are priorities for parents. ‘Respect and valuing of individual expertise by health professionals and an environment conducive to negotiation, allow both parent caregivers and the child input in deciding the type and extent of involvement and participation with which they feel most comfortable’. 66

What we learnt from the literature comes predominately from small-scale, single-site studies highlighting the need to examine how hospital care is delivered to, and experienced by, children with LD and their parents at a national level. Furthermore, no studies have directly compared the views of parents of hospitalised children with and children without LD, which means that we currently lack evidence of what things affect all families and what things are unique to the learning disabled population. The central focus of research about the care of children with LD in hospital has been staff and parents, rather than the experiences of children themselves. Children with LD were at the centre of our study and, wherever possible, their views and experiences were captured first hand. Children’s experiences of hospitalisation are, in the main, mediated by adults, parents/family members and health-care staff; it was important in our study to capture all of these views.

Section 2 Research design, methods and analysis

Chapter 4 Research methods

The aim of this section is to provide an overview of the study design and the methods of data collection. Each of the four phases is described in turn, followed by a section on data analysis for all phases and our patient and public involvement (PPI) activities. The original study protocol has been published1 and parts of this chapter have been reproduced from that publication [published by the BMJ Publishing Group Limited. For permission to use (where not already granted under a licence) please go to http://www.bmj.com/company/products-services/rights-and-licensing/. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text].

A list of protocol amendments is provided in Report Supplementary Material 2.

Research design

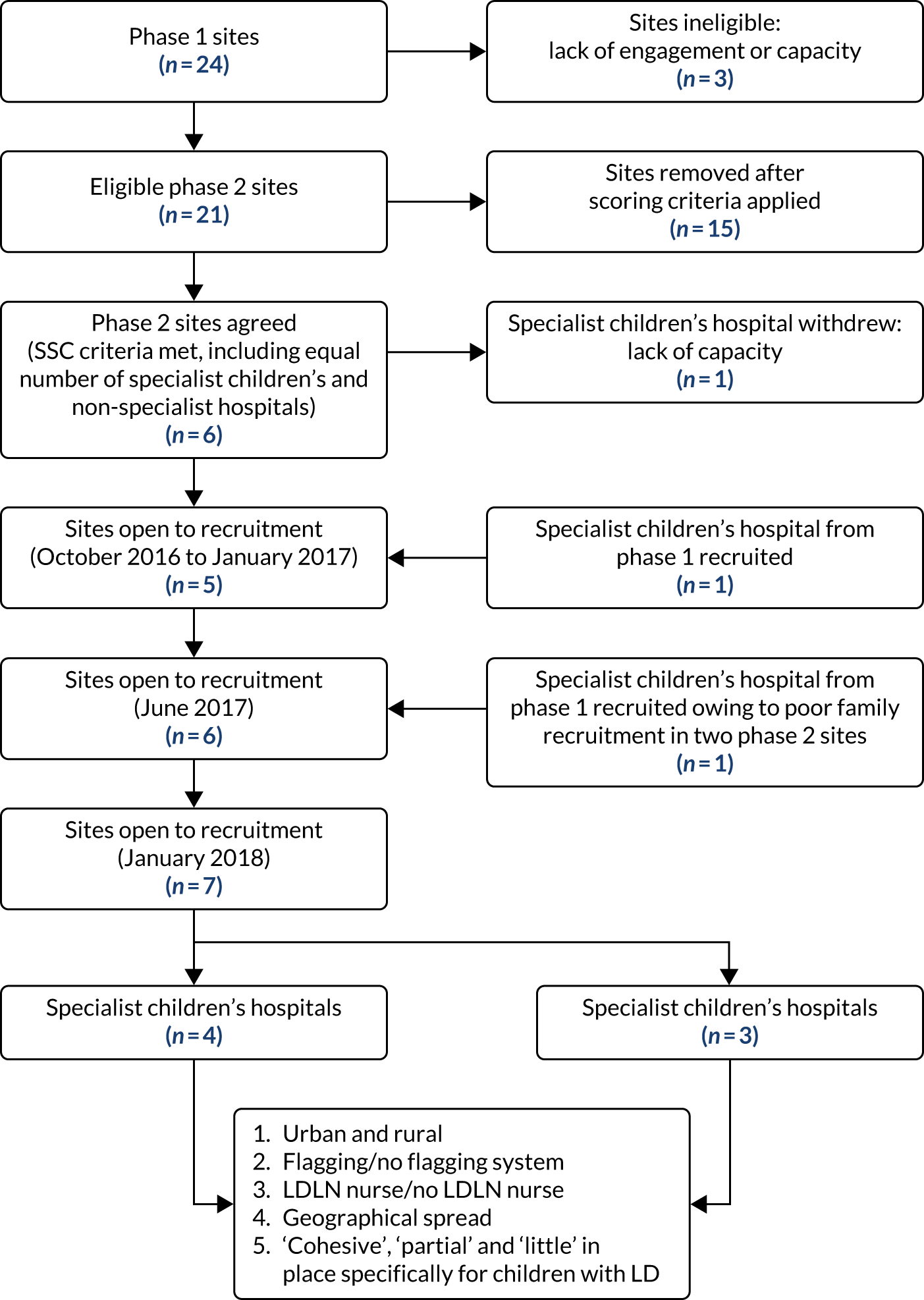

A transformative, mixed-methods case study design67 was used, integrating quantitative and qualitative methods across four phases over 3 years (Figure 2). Acknowledged for giving ‘a voice to the powerless and voiceless’,68 the case study approach enabled the views of children with LD and their parents to be prioritised and explored ‘in depth and within its real-life context’. 69 In this study, a single hospital site represented each case, and seven cases (phase 2) were included: four specialist children’s hospitals and three non-specialist hospitals. For every two children with LD recruited one child without LD was also recruited, allowing the experiences of the two groups of patients to be compared. Data from diverse sources were synthesised to enable an understanding of whether or not children with LD and their families receive equal access to high-quality hospital care and services. The production of thick, rich descriptions of the phenomena, using in-depth interviews and creative research methods, meant that the complexities of the situation and the factors that can contribute to those complexities emerged. 70

FIGURE 2.

Four-phase transformative mixed-methods study design. The numbers included in the figure are recruitment targets and not the actual recruitment numbers.

Phase 1 involved mapping the organisational context for the delivery of hospital care to children with LD, as well as comparing hospital staff members’ perceptions of their ability to identify the needs of children with and children without LD and their families and to provide high-quality care to effectively meet those needs.

Phase 2 compared how hospital care and services are experienced by children with and children without LD and their families, and staff members’ views of caring for them. A sample of staff from NHS community trusts were also surveyed.

Phase 3 used child and parent questionnaires to compare levels of satisfaction with inpatient hospital care.

Phase 4 synthesised the study findings to develop the outline content for a staff training DVD (digital versatile disc).

Approvals

Full ethics and health research authority approval for this study was obtained prior to the study commencing (London–Stanmore Research Ethics Committee: reference 16/LO/0645). Local research and development approval was also obtained from each of the 24 participating hospital sites.

Phase 1 research methods and analysis

Sample and setting

Children in England are treated either in specialist (tertiary) children’s hospitals (which may stand alone or be part of a wider NHS trust) or in general hospital settings (secondary care) that have one or more paediatric wards. All 15 specialist children’s hospitals in England agreed to participate following an invitation e-mail sent to the trust’s chief nurse through the Association of Chief Children’s Nurses (ACCN). 71 A sampling strategy informed the recruitment of a selection of non-children’s hospitals, based on their proximity and referral patterns to the specialist children’s hospitals and their throughput of children with LD. Senior clinical or managerial staff with a specific responsibility for LD or those working in a dedicated LD role were eligible to participate in the interviews. All clinical and non-clinical hospital staff who had contact with children were eligible to complete the survey. A local collaborator for each participating site was identified.

Recruitment and consent

Staff who were eligible for interview were identified and approached by the local collaborator and given an information sheet and a consent form. With the staff member’s permission, their contact details were given to the research team, who telephoned the staff member to answer any questions and agree a date for the face-to-face or telephone interview. Staff who were eligible to be surveyed were e-mailed a link to an online survey by the local collaborator, with paper copies also available. The return of a completed survey was taken as consent to participate.

Data collection

Staff interviews

Interviews were semistructured, followed an interview guide (see Report Supplementary Material 3), and focused on the delivery of services to children with LD at the organisational level, including policies, systems and practices. Interviews lasted 30–45 minutes and were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. A minimum of two interviews per site were planned to ensure completeness of data.

Staff survey

A review of the literature informed the survey development in consultation with experts in the field and parent members of the Study Steering Committee (SSC). The survey, which was anonymous, had two parts; the first focused on children with LD and long-term conditions and the second focused on children without LD with long-term conditions. The survey focused on five elements of care (capability, capacity, confidence, safety and values) for those with and those without LD, with additional questions regarding access to care and processes used to identify and track those with LD. Likert scales were used for each question, with the majority of questions rated on a five-point scale of ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’. Definitions of LD and long-term conditions were provided for clarification (see Report Supplementary Material 4).

Hospital policies

Sites were asked to provide policies related to the following areas of practice: (1) LD policy (or equivalent), (2) patient (children and young people) experience, (3) child protection, (4) complaints, (5) safeguarding, (6) communication and (7) restraint and holding.

Phase 2 research methods

Phase 2 compared how hospital care and services are experienced by children with and children without LD and their families, and staff’s views of caring for them. A sample of staff from NHS community trusts were also surveyed.

Setting and sample (hospital sites)

A subset of phase 1 hospitals participated in phase 2 data collection, based on the:

-

strength of the organisational context for delivery of care to children with LD

-

staff’s perceived ability to identify and meet the needs of children with LD

-

appointment of a learning disability liaison nurse who had the remit to improve care for children with LD.

To enable an objective selection of sites, scoring criteria were developed by the SSC, which was provided with anonymised information relating to four domains: (1) phase 1 recruitment, (2) hospital facilities and geography, (3) model of care and (4) phase 1 survey results. The executive team applied the scoring criteria, a shortlist was compiled and seven hospitals were included: four specialist children’s hospitals and three non-specialist hospitals (see Appendix 1, Figure 34). All sites had a principal investigator who was responsible for the study and a research nurse or equivalent who screened and approached eligible patients and provided day-to-day contact for the research team.

Sampling (participants)

Phase 2 involved data collection with a range of parents and children and staff working in both the hospital and the community (Table 1). A range of inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied (see Appendix 2).

| Participants | Sampling strategy | Sample size |

|---|---|---|

| Children and parents | A purposive sampling strategy using a sampling matrix to ensure diversity according to severity of LD, age, admission type, length of stay | 56–64 families |

| Hospital staff | A purposive sampling strategy using a sampling matrix to ensure diversity in terms of professional role. Includes subset of staff identified by families as potential participants | 112–28 |

| Ward managers | One from each study ward | 12 |

| Community staff | A convenience sample of staff from NHS community trusts providing health-care services to children in geographical proximity to the phase 2 hospital sites | 280–320 |

We did not recruit children aged ≥ 16 years because we anticipated that they would be in the process of transitioning to adult services, which would make it challenging to draw out similarities and differences in care and for children to be able to accurately reflect on only children’s services, and also because of the increasing body of work related to transition generally.

Operational definition of learning disability

The theoretical definition of LD is not always easily operationalised in practice. Among very young children, only severe LD is likely to be apparent,72 and some children never receive a formal diagnosis of LD, with medical records often stating ‘global developmental delay’ or a ‘syndrome without a name’. For the purposes of the study, a child was classified as having LD if any one of the following was documented in their medical notes:

-

a diagnosis of LD

-

a condition always accompanied by a degree of LD (e.g. Down syndrome)

-

global developmental delay

-

attendance at a special needs school accompanied by the parent verbally confirming that the child had LD.

Matching children and young people without learning disability

Children without LD were screened using four matching criteria: (1) age (5–7 years, 8–11 years or 12–15 years and 364 days), (2) expected length of stay (short, 1–2 nights; medium, 3–7 nights; long, ≥ 8 nights) and (3) reason for admission (surgical, medical or investigations/tests).

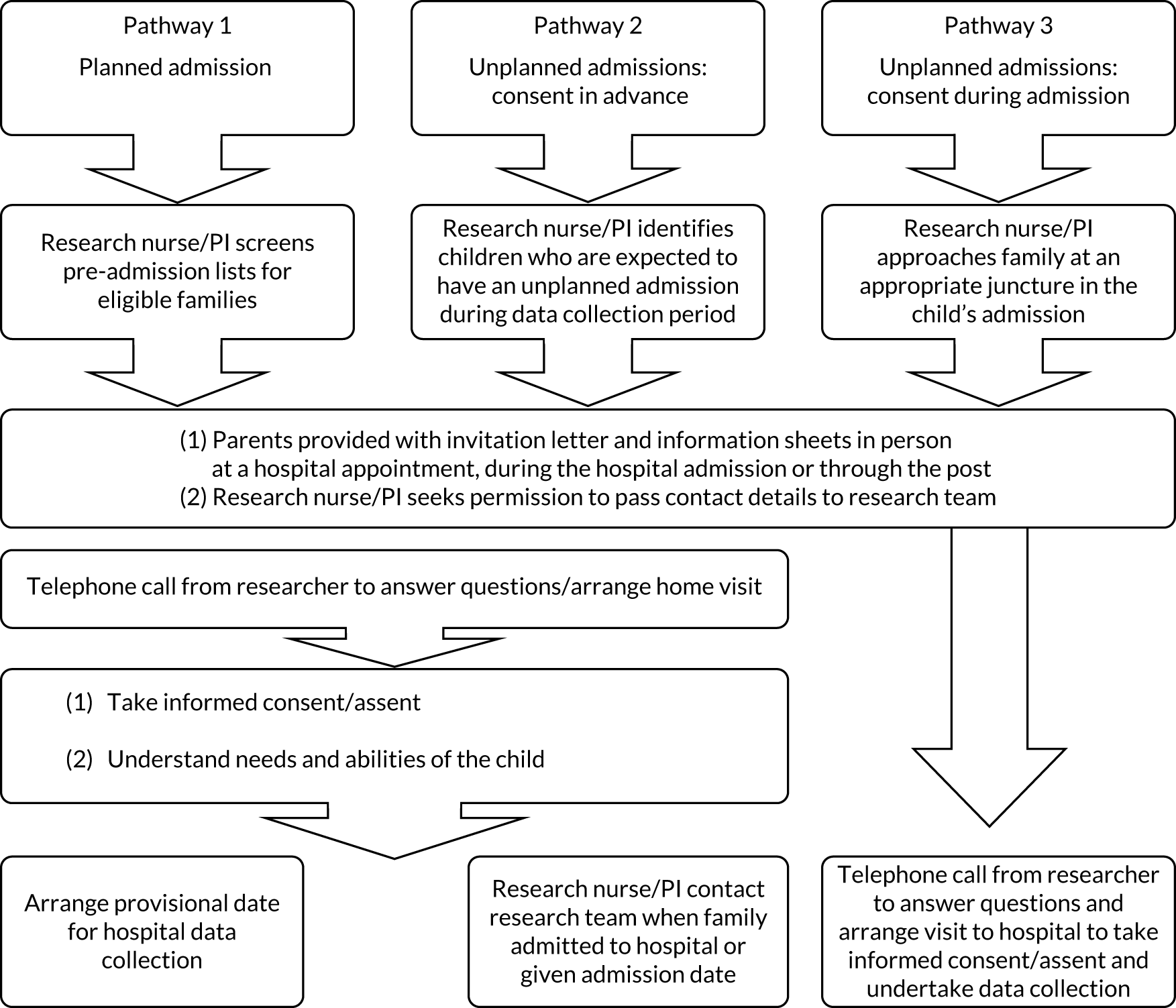

Recruitment and consent

Families

There were three pathways to recruiting and consenting children and their families (Figure 3). All children were invited to participate irrespective of their abilities. The researchers ensured that all participants understood what was being asked of them and that they could have a break or withdraw from the study at any time. Four versions of patient information leaflets were available so that children of different ages and abilities could be included: two were symbol based (see Report Supplementary Material 5) and two were word based (see Report Supplementary Material 6). Children who took part provided verbal or written assent, and their agreement was confirmed just prior to data collection. When possible, the consent/assent process took place in the family home to enable researchers to build rapport with families, ascertain the child’s abilities and interests to tailor data collection activities and ensure that the study questions were relevant and sensitive.

FIGURE 3.

Pathway to recruitment: families. PI, principal investigator.

Hospital staff

During the parent interview, participants were asked to identify hospital staff involved in the care of their child whom they were happy to be invited for interview. These staff names were given to the research nurse, who established the willingness of these staff members to participate. The research nurse also identified and approached additional staff, and provided them with an information sheet and a consent form. With permission, the contact details of staff interested in participating were given to the research team, who contacted them to answer any questions and arrange a mutually convenient time for data collection.

Community staff

Each local collaborator distributed the online survey by e-mail. The front page of the survey provided a synopsis of the study, guidance for completing the survey and study contact details. Submission of the survey was taken as consent to participate.

Methods of data collection with parents

Parents were invited to share their experiences through four data collection methods: hospital diary, photographs, safety review form and an interview following the child’s discharge. The diary offered flexibility in how parents shared their experiences and could be completed at any time of the day/night. Completing parent interviews post discharge enabled researchers to prioritise data collection with children during the hospital admission.

Hospital diary

Paper diaries and a pen were provided in an envelope, and parents were asked to leave these on the ward prior to discharge so that the research nurse could collect them. Guidance on completing the diary was provided, including prompts about who they had interacted with, what information they had been given, decisions that had been made and how they felt about what had happened. Space was provided for further reflections.

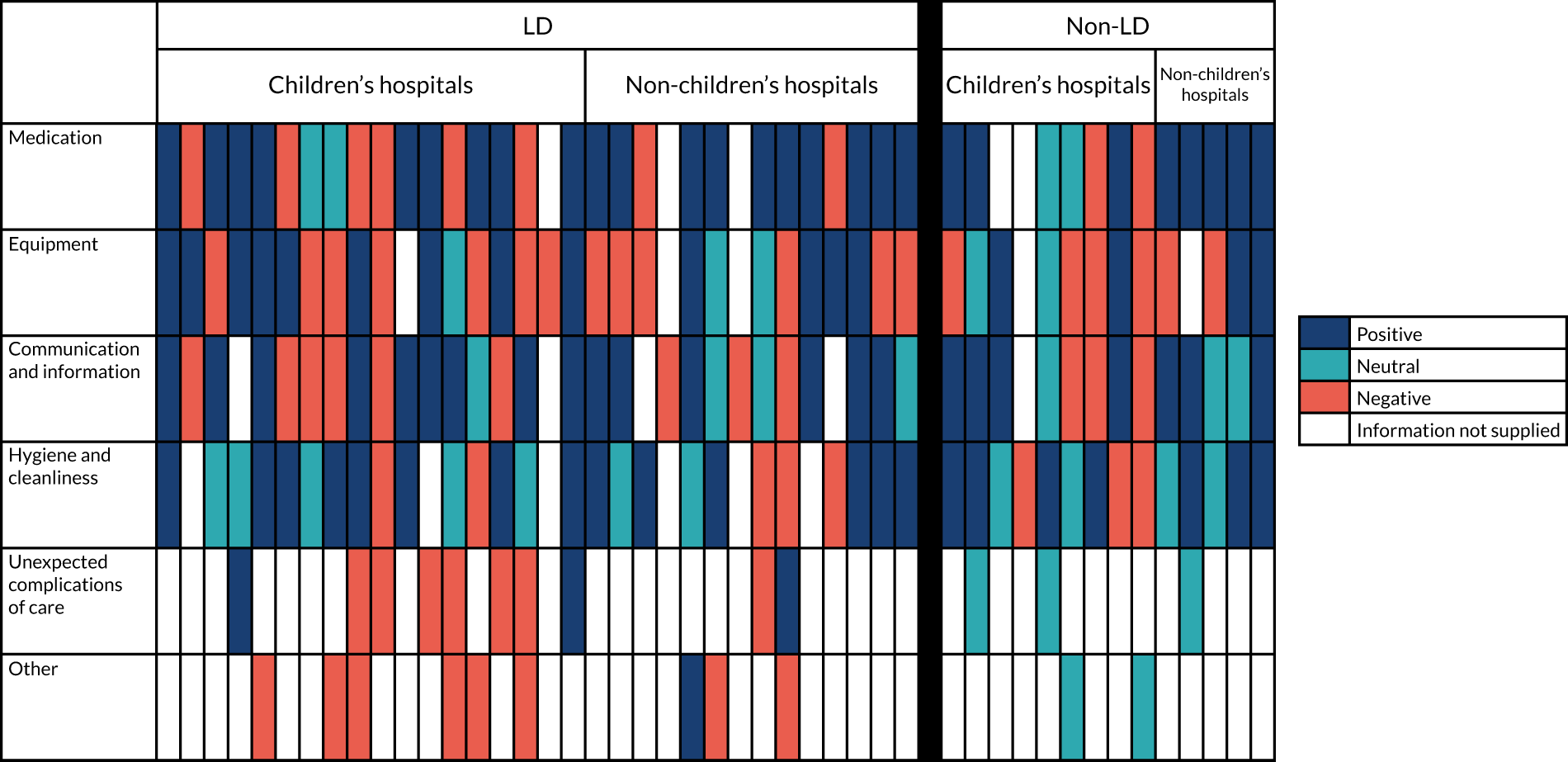

Safety review form

The SHINE tool73 was adapted for parents to document positive and negative aspects of their child’s care in relation to six areas of safety: medication, communication and information, equipment, unexpected complications of care, hygiene/cleanliness and ‘other’ (see Report Supplementary Material 7). Parents could also indicate whether they had seen something that was unsafe, and whether or not this had been dealt with. The form was completed just prior to the child’s discharge, or, if it was not, the researcher completed the form with parents during their home interview.

Photography

Parents were asked to capture images of three things that they thought worked well and three things that could be improved about their hospital experience using a camera provided.

Semistructured interview

Interviews were planned for as soon after the child’s discharge as possible. Flexibility was offered in terms of location and timing and also the format (either face to face or over the telephone). Interviews focused on the child’s recent hospital admission, and how the experience differed or not from previous admissions to the same or different hospitals. The semistructured interview guide (see Report Supplementary Material 8) included questions about the child’s needs and whether or not these were identified and met, and the role parents played. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. All families were given a short study evaluation form to complete (see Report Supplementary Material 9).

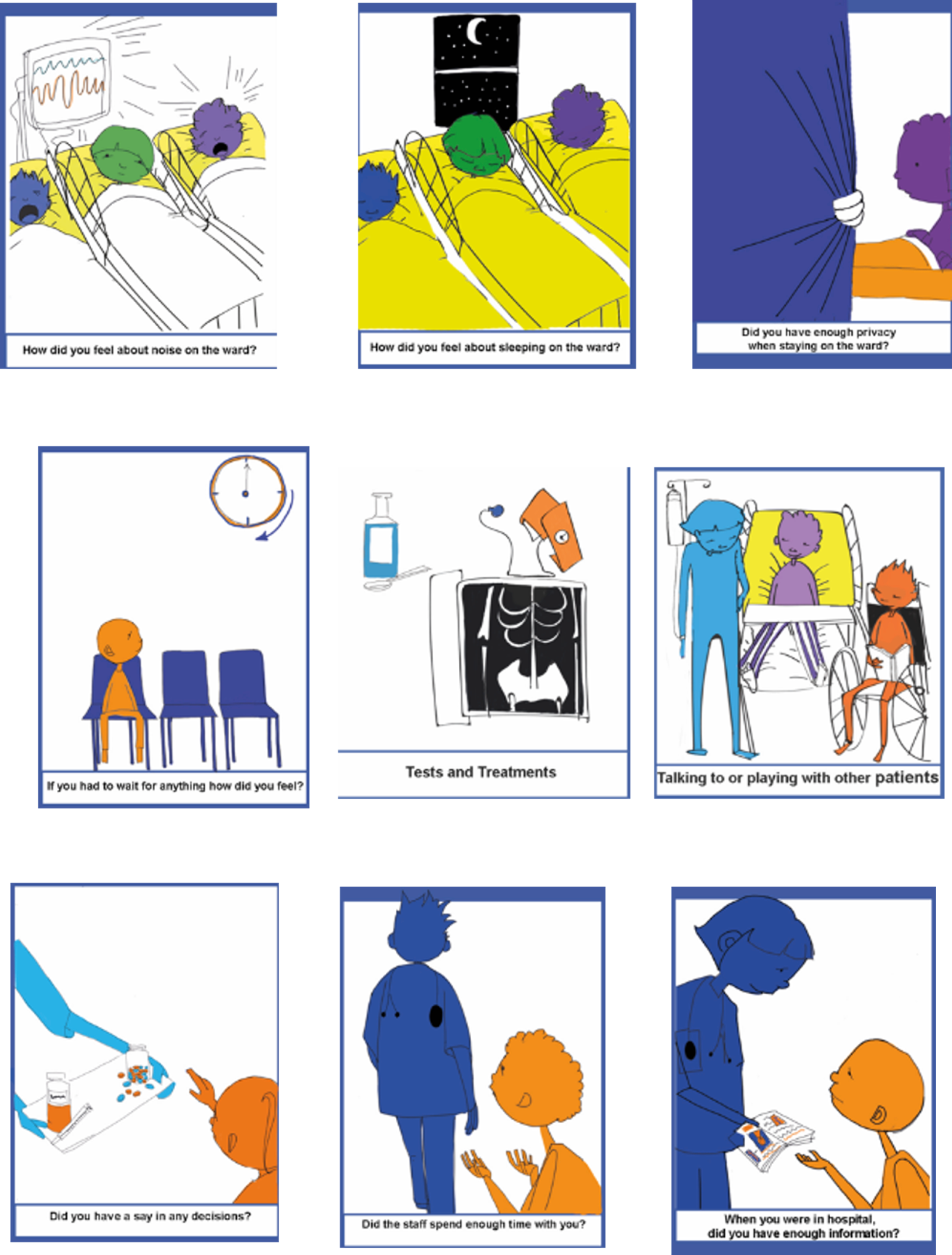

Methods of data collection with children

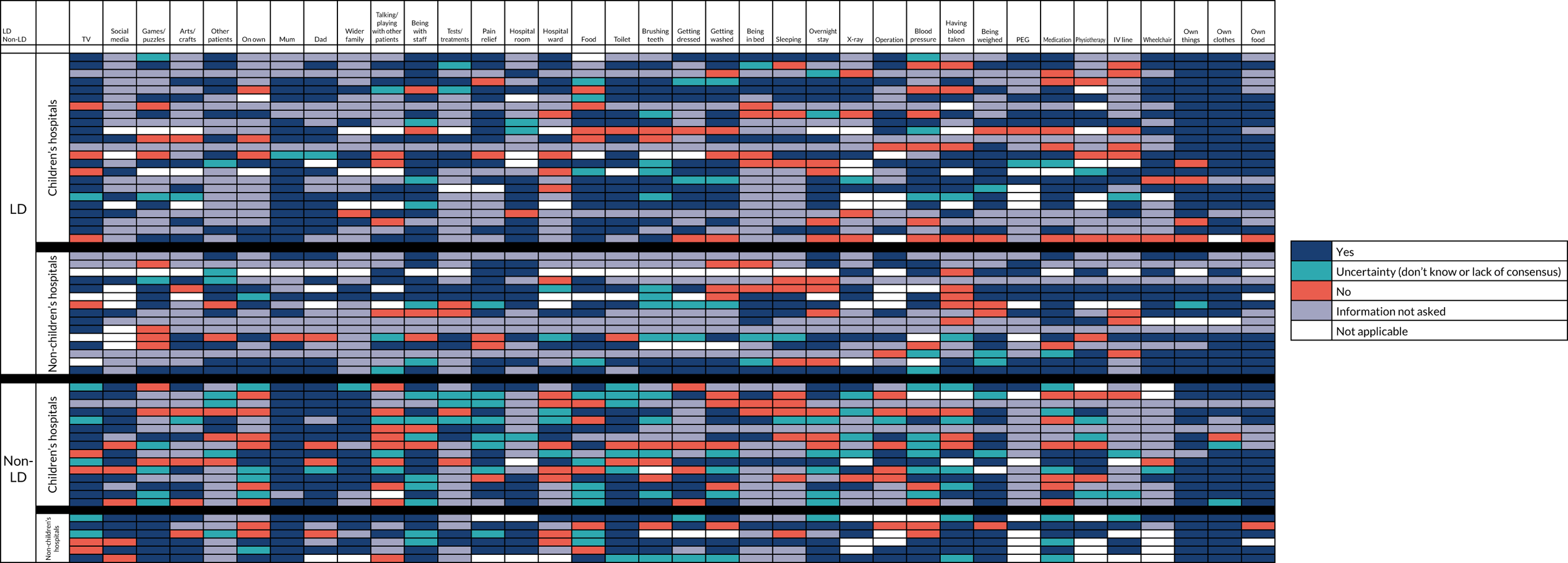

A multimodal approach was used based on the premise that children are experts about their own lives and should be enabled to share their experience in accordance with their abilities and preferences. Researchers spoke to parents on the telephone in advance of data collection to ascertain how the data collection activities needed to be tailored for the child. Three activities were available to elicit data: Modified Talking MatsTM (Talking Mats Centre, Stirling, UK),74 a sticker exercise and a hospital tour. For children unable to participate themselves, parents were invited to participate as a proxy, providing answers from the perspective of their child. Data collection primarily took place at the bedside. With permission, data collection sessions were recorded and transcribed verbatim. A retrospective review of children’s medical notes was also undertaken.

Modified Talking Mats

Talking Mats74 is a communication symbol tool designed by speech and language therapists that uses picture symbols to assist people with a range of communication difficulties in expressing themselves. It has been used with people with LD. A professional artist was commissioned to produce the additional symbols needed for data collection (see Appendix 3), which were then checked with children with and children without LD to ensure that each illustration was a clear and accurate representation of the person/place/object/concept we were wanting to portray. Talking Mats has a ‘top line’ showing a character with a thumbs-up, a thumbs-down or a shrug of the shoulders, which were used in the study to denote ‘like’, ‘don’t like’ and ‘not sure’. For children who required concrete ‘like’ or ‘dislike’, the middle option of ‘not sure’ was removed. Children were presented with a range of symbol cards relevant to their inpatient experience, and they were asked, depending on their ability, to indicate or to physically place these under the appropriate top line card. Depending on the ability, engagement and concentration of the child and their specific hospital experience, the number and type (abstract vs. concrete) of symbol cards varied. Children were encouraged to elaborate, where possible, their feelings about the placement of each card. Children could indicate their preferences verbally, with eye gaze, using communication software or with their parents as communication partners.

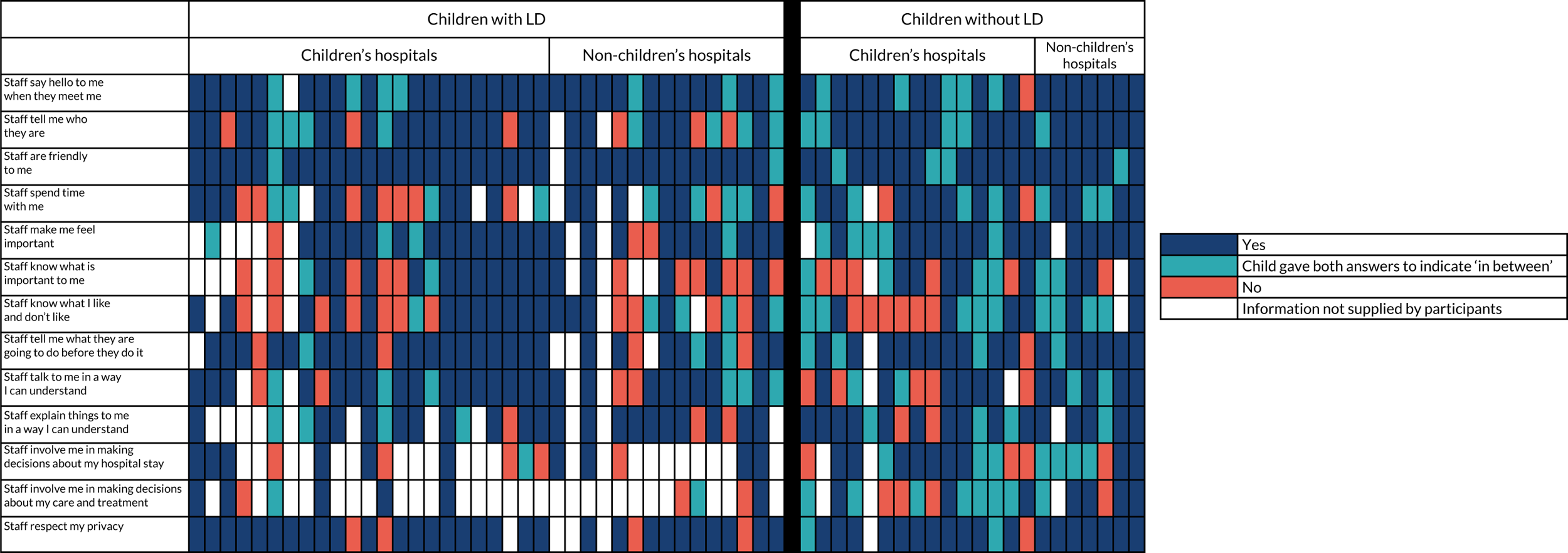

Sticker exercise

Children were given a short survey about their interactions with hospital staff and a set of red (frown) and green (smiley) face stickers to indicate a yes or no response to each question. Three versions of the questionnaire were produced: a shorter and longer version using symbols and words (see Report Supplementary Material 10) and a word-only version (see Report Supplementary Material 11), with the addition of frequency responses to indicate how often something did or did not happen. This tended to be used with children who had higher cognition. The researcher read each question aloud, where necessary, and supported those with physical impairments to place their sticker.

Hospital tour with photography

To help children think about their hospital experience, we invited them to take the researcher on a hospital ‘tour’, identifying areas they had accessed during their admission and taking photographs using a digital camera. In practice, tours led by the child focused on the ward or bed space. If a child could not physically take a photograph, their parent or the researcher would take it on their behalf, from the child’s perspective. With the agreement of the child, the ‘tour’ was audio-recorded to capture data relating to what was being photographed. Children were free to take photographs of anything they chose, with the exception of other patients, visitors or identifiable information. Photographs of a member of hospital staff required the approval and written consent of that person. Immediately following the tour, the photographs were printed or viewed on the researcher’s laptop, depending on the child’s preference, and discussed. All children (or their parents) were offered copies of the photographs to keep.

Retrospective mapping of hospital appointments

A retrospective mapping of all inpatient stays and outpatient appointments for the preceding 2 years at the participating hospital was conducted using paper and electronic hospital records for each child and the electronic appointment system. Data from inpatient (e.g. age, diagnosis, treating team, date of discharge, hospital passport, reasonable adjustments) and outpatient (e.g. date and time of appointment, if they did not attend) records were collated in a Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet.

Methods of data collection with staff

Hospital staff interviews

Interviews were conducted over the telephone or in person in a quiet room in the hospital, depending on the participant’s preference, using a semistructured interview guide (see Report Supplementary Material 12). Interviews lasted 30–60 minutes and were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Community staff survey

The phase 1 staff survey was modified, with questions added relating to access to secondary and tertiary care for children with and children without LD (see Report Supplementary Material 13). This was administered as per the phase 1 survey and stayed open for 3–5 weeks.

Phase 3 research methods

The aim of phase 3 was to compare the levels of satisfaction with hospital care between (1) children with and children without LD, and (2) parents of children with and parents of children without LD.

Recruitment and sampling

All seven phase 2 hospitals participated in phase 3, with data collection taking place on up to four wards identified by the principal investigator. All children and their parents who were admitted during the data collection period were eligible to participate. To facilitate the distribution and collection of surveys, no exclusion criteria were applied, and parents were asked to indicate if their child had a long-term condition, LD, neither or both. Participants were advised that returning a completed survey was taken as their consent to participate.

Data collection

An ‘easy-read’ survey (see Report Supplementary Material 14), based on a patient-reported experience measure developed by children and young people for children and young people,75 was developed for all children, irrespective of their age or perceived ability. An artist was commissioned to develop images to sit alongside each question, with a corresponding ‘thumbs-up’ or ‘thumbs-down’ and ‘smiley’ or ‘sad face’ tick box that children could use to indicate their response. The survey, available in English only, was piloted with inpatients at Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH) school, with and without LD, and minor revisions were made. Children could complete the survey independently or assisted by their parent, or the parent could complete it on the child’s behalf if the child was unable to. The parent survey (see Report Supplementary Material 15) contained a range of questions, the majority using a five-point Likert scale response. Non-English versions were available in seven languages. Wards were supplied with postboxes for completed surveys, which were collected by the research nurse and couriered to the research team.

Phase 2 and 3 data analysis

Qualitative and quantitative data were analysed in each phase before being merged and connected using data synthesis; congruence and incongruence between data sets was sought. Each data set was analysed by at least two members of the research team. Barriers to and facilitators of high-quality hospital care were identified for each data set, and these were then brought together, allowing a comparison of the factors identified by staff, parents and children. Specific examples of successful and effective measures that promote equal access were also identified. The analytical framework was compared with our initial theoretical framework in order to generate a final empirical framework of factors that affect the promoting of equal access to high-quality hospital care for children with and children without LD and their families.

Qualitative data analysis

The approach to analysis was relevant to each method of data collection; this is detailed in Table 2.

| Phase | Data | Method of analysis | Summary of analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Staff interviews | Framework analysis52,53 | Staff interviews were entered into NVivo 11; analysis was within and between data, applying the stages of framework analysis76 |

| 2 | Hospital documents | Summative content analysis77 | Predefined terminology (LD, special needs, intellectual disability, developmental delay, reasonable adjustments) was used to ascertain references to children with LD, creating a thematic framework based on content. The first set of documents was examined in detail and a coding frame was developed for use with subsequent documents |

| 2 | Parent interviews | Thematic analysis78 | Parent interviews were entered into NVivo 11 and read by at least two members of the research team; schematic maps were produced, checked and discussed further at team analysis meetings |

| 2 | Parent diaries | Thematic analysis78 | A subset of 20 diaries was read independently by two members of the research team, who then met to discuss the content and broad themes identified. An initial framework was developed and used when coding the diary content in NVivo 11, broadly identifying positive and negative experiences |

| 2 | Safety review form | Conventional content analysis77 | Data were extracted from the forms and summarised in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet using the six domains. Cells were colour coded, and highlighted by one researcher as green indicating a positive issue, red indicating a negative issue and orange indicating in between. The spreadsheet was checked by a second researcher and minor revisions were made. Content analysis aided the counting and reporting of themes |

| 2 | Children’s interviews |

Counting to produce visual maps Thematic analysis78 |

Completed Talking Mats interviews and sticker charts were analysed for the frequency of responses, VILD charts produced to present data, interview data were analysed thematically |

Quantitative data analysis

Staff survey data (phases 1 and 2)

Descriptive statistics were used to characterise the sample. Composite variables were computed to represent capability, capacity, confidence, safety and values separately for questions related to LD and no LD (see Appendix 4, Table 15). All composite variables had acceptable internal reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha values of > 0.7. Composite variables and individual questions about involvement in service delivery and planning services, safety, values and meeting needs were analysed using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, comparing responses about children with LD with those about children without LD for the total sample and, for hospital staff (phase 1), separately for respondents from children’s and non-children’s hospitals. Responses from community staff were also compared about admission and discharge (phase 2) for children with and children without LD using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. Differences between children’s and non-children’s hospitals or between hospitals with and hospitals without LD nurse provision were compared using Mann–Whitney tests.

Parent and child satisfaction data (phase 3)

For the purposes of this report we focused on responses from parents and/or children with a long-term condition, with and without LD. Descriptive statistics were used to characterise the sample. Composite variables representing key domains related to satisfaction with care to meet their child’s needs, staff interaction and communication (parent survey) and environment, people, and care and treatment (child survey) were calculated (see Chapter 11). All composite variables on the parent survey had satisfactory internal reliability (Cronbach’s alpha > 0.8); all Cronbach’s alpha values for the composite variables in the children’s survey were > 0.6. Responses were compared separately for children with and children without LD and parents of children with and children without LD using Mann–Whitney, chi-squared or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate. For all surveys in each phase, a Bonferroni correction for multicomparisons was made, resulting in an alpha level of 0.005. All data were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 22 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Phase 4

Findings from phases 1–3 were synthesised and shared with hospital staff at the phase 2 hospitals, and an open dissemination event was held at GOSH on 18 June 2019. The aim of this was to generate discussion to inform the development of a LD training package for staff. The views of families were also sought through discussion with individual patients on the ward and consultation with members of the Parent Advisory Group (see Parent Advisory Group).

Patient and public involvement

Aim

Patient and public involvement has been central to our work from the outset, with our primary aim being to ensure that the study was carried out in an appropriate, accessible and sensitive manner.

Preparation of proposal for grant funding

This study evolved from four pieces of work involving the chief investigator (KO) and/or other members of the research team (FG, JW, ITW). Key to each of these was our commitment to hearing what matters most to participants. The chief investigator consulted widely with parents, staff and LD experts about the RQs, design, data collection methods and dissemination to ensure that these were acceptable, feasible and of importance. One parent said: ‘Very important – LD are overlooked. My local trust only appointed a LD nurse advisor following a death, which was far too late’. Our parent co-applicant (SK) provided valuable insights and expert PPI throughout the study.

Involvement since grant funding

Parent Advisory Group

A group of 8–10 parents of children with and children without LD who had used hospital services was established to advise on all phases of the study. The Parent Advisory Group met twice per year during the study, with contact between meetings taking place by e-mail for specific requests and study updates. Representatives of the Parent Advisory Group attended three of the four of SSC meetings and fed back to other Parent Advisory Group members.

Phase 1

The Parent Advisory Group gave feedback on the preliminary results from the interviews in a sense-checking exercise to ascertain if the findings resonated with their experiences; this resulted in changes to the phase 2 parent interview topic guide.

Phase 2

The Parent Advisory Group gave feedback on data collection with children, parents and hospital staff. This was either during face-to-face meetings (Table 3) or at the Study Steering Committee meeting, where the group was involved in the ranking exercise for the selection of phase 2 sites and the challenges associated with phase 2. Additional feedback was elicited between meetings by e-mail on aspects such as the layout and instructions of the parent diary, the appropriateness of the parent safety review tool, and the content and layout of the information sheets and consent forms.

| Area of feedback | PPI | |

|---|---|---|

| Staff | Hospital staff recruitment | Recruitment procedure |

| Community staff survey | Suggested content | |

| Parent | Recruitment | Acceptability of procedure |

| Diary | Acceptability/feasibility of method and process | |

| Safety review form | Acceptability/feasibility of method and process | |

| Interview process | Acceptability/feasibility of method and process | |

| Interview topic guide | Suggested content | |

| Children | Use of cameras | Acceptability/feasibility of activity |

| Talking Mats | Acceptability/feasibility of activity | |

| Arts and crafts activities | Acceptability/feasibility of activity |

Phase 3

Feedback was provided on the style, format and administration of the survey to parents, as well as the clarity of questions and completion time. Parents’ knowledge of being in hospital, receiving care and navigating the system was hugely informative, resulting in timely changes to the survey. For the children’s survey, revisions were made to the wording of some questions, ideas were provided for pictures to accompany questions and some questions were moved to the parent survey.

Study Partnership Schools

Two local special educational needs schools, Richard Cloudesley School and The Bridge School, agreed to be Study Partnership Schools. One member of staff was pleased that the students had been asked to help, as it was felt that they were often overlooked for similar opportunities.

Discussions about the methods for collecting data from children were held, and school staff chose to trial the activities that they felt would benefit their students the most. In one school, a class trialled the photograph elicitation activity by taking photographs of their school and documenting what they liked and disliked. These photographs were subsequently used to produce an ‘about my school’ book to help familiarise new students with the school. In the other school, students trialled Talking Mats using photographs and picture symbols to share what they liked and disliked about their curriculum and school environment. A summary of each child’s participation was produced for the class teachers. Both schools were offered a presentation of the phase 1 study results. The opportunity to trial the methods was invaluable for assessing feasibility, strategies for delivery and the extent of student interest and engagement. Staff also gave helpful advice on elicitation techniques used in classroom settings for children with LD.

Students in the GOSH school provided feedback on proposed designs for picture–symbol cards for use with Talking Mats and the children’s survey. Students were asked to describe each picture and what changes could be made to improve clarity. They indicated their preferences for thumbs-up/thumbs-down, smiley faces/sad faces or ticks/crosses for the response options.

Young People’s Advisory Group and Young People’s Forum

Great Ormond Street Hospital runs two groups to provide researchers and clinicians with feedback on research and clinical services. The GOSH Young People’s Advisory Group, comprising 8- to 19-year-olds, is part of a national network of Young People’s Advisory Groups that meets regularly with the remit to be involved in the design and delivery of clinical research to ensure that it is relevant to children, young people and families. The Young People’s Forum, comprising children and young people aged 10–21 years, aims to improve the experiences of teenage patients. Both groups gave feedback on the proposed phase 2 research methods for children, including trialling aspects of the ‘hospital tour’ photograph elicitation activity by taking photographs of public access areas at GOSH and discussing these based on their experience of their own hospital admission. This process informed the practical set-up and delivery of this method of data collection.

We successfully integrated PPI into our research, underpinned by the research team’s belief that PPI is a worthwhile pursuit. Our Parent Advisory Group was pivotal; the members have provided input throughout, and we would highly recommend having a dedicated PPI co-ordinator, supported by other members of the research team. We extend our thanks to all of our PPI partners who have contributed to our study.

Section 3 Results

The results section comprises five chapters. The first three focus on findings from staff, with data from the survey used to identify whether or not staff perceive that inequality exists between children with and children without LD and their families (see Chapter 5). Findings from the organisational mapping exercise (see Chapter 6) and staff interviews (see Chapter 7) subsequently highlight the cross-organisational, organisational and individual staff factors in NHS hospitals that facilitate and prevent such inequality.

Chapters 8–10 focus on parents’ experience of being in hospital with their child with LD. These draw primarily on data from home interviews, supplemented by findings from the parent diaries and safety review form. Parents’ views on how well their child’s needs are met in hospital are reported, as are perceptions of their own role and the impact of hospitalisation on their health and well-being. Comparisons are made with data collected from parents of children without LD. The barriers to and facilitators of children with LD receiving equal access to high-quality hospital care that meets their particular needs are drawn out. Chapter 11 focuses on the findings from the parent and child survey about satisfaction with different aspects of the hospital experience. Findings from children are presented alongside data from the Talking Mats and sticker exercise.

The findings presented should be considered in the context of the Equality Act 2010,79 which sets out the legal duty health-care services have to consider the needs of all people with disabilities, including children, in the way that they organise their buildings, policies and services. This does not mean treating everyone the same but rather it means taking reasonable steps to avoid disadvantage arising from any provision, criterion, practice, physical feature or lack of auxiliary aid that puts any child at a substantial disadvantage. 79 These ‘reasonable adjustments’ reflect the fact that some people with disabilities may have particular needs that standard services do not adequately meet80 but are entitled to expect equality in the outcomes of their hospital stays. It is recognised that people, including those with disabilities, can experience discrimination not just from individuals but from entire organisations such as hospitals, albeit unintentionally. 79 Discrimination includes a child being treated unfavourably because of something arising as a consequence of their disability or if it cannot be shown that their treatment is a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim. The only exception is if it can be shown that the person/provider did not know, and could not reasonably have been expected to know, that the child was disabled.

The findings must also be considered in the context of discussions about equal access, equality and equity. Equal means ensuring that everyone has equal opportunities, with no one being treated less favourably because of who they are or what makes them different from other people. 81 Both equality and equity promote fairness, but via different means: the former through ‘treating everyone the same regardless of need’ and the latter through ‘treating people differently dependent on need’. 82 As highlighted by Social Change UK, ‘If equality is the end goal, equity is the means to get there’ (reproduced with permission from Social Change). 82 An essential point is that treating people the same does not necessarily result in equity of outcome. Distinguishing between equality and equity is not necessarily straightforward, especially because the two terms are inextricably linked and sometimes used interchangeably. 83,84 As Northway83 suggests, ‘a failure to make the necessary adjustments to promote equality of access to healthcare results in inequity’ (© 2022 University of Hertfordshire). 83 In this study, we have been able to generate a large body of evidence about the way in which hospital inpatient care is delivered to and experienced by children with LD and their parents, from the perspective of multiple stakeholders, as well as drawing comparisons with children without LD and their families. Although we did not formally measure whether or not children and young people with LD experience equitable outcomes, our focus on equality revealed a lack of individualised hospital care for those with LD based on their particular needs, as well as a lack of policies, systems and processes to facilitate this. Our findings support the principle that ‘working towards equity and not just equality requires . . . seeing another person and their situation clearly enough to understand that what works for one does not work for all’. 85 Thinking equitably may help those providing care to think more pro-actively about the need for reasonable adjustments83 and is an important factor in changing clinical practice going forward.

Chapter 5 Staff survey

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Oulton et al. 86 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Kenten et al. 87 © 2019 The Authors. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd. This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The aim of this chapter is to present the results from an anonymised online survey of 2261 hospital staff working across 24 NHS hospitals across England (phase 1) and 429 community staff associated with a subset of seven of these hospitals (phase 2) (Table 4). Our target sample size for the hospital survey was 1800, which we exceeded, but our method of approaching eligible staff for survey completion (via local collaborators in the hospitals and community) precluded being able to determine response rates.

| Method | Number of hospital sites | Number of participants | Staff group (n) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doctor | Nurse | Allied health professional | Health-care assistant | Other | |||||

| Hospital | |||||||||

| Survey | 24 | Children’s hospital (n = 15) | 2261 | Children’s hospital (n = 1681) | 272 | 762 | 308 | 79 | 260 |

| Range per site (38–202) | |||||||||

| Non-children’s hospital (n = 9) | Non-children’s hospital (n = 580) | 105 | 222 | 67 | 50 | 136 | |||

| Range per site (7–131) | |||||||||

| Community | |||||||||

| Survey | 7 | Children’s hospital (n = 4) | 429 | Children’s hospital (n = 285) | 21 | 57 | 100 | 22 | 85 |

| Range per site (12–202) | |||||||||

| Non-children’s hospital (n = 3) | Non-children’s hospital (n = 144) | 11 | 32 | 32 | 19 | 50 | |||

| Range per site (31–70) | |||||||||

The results are used to help answer four of our five RQs (RQ1, RQ2, RQ3 and RQ5) related to inequality between children with and children without LD and their families. We also provide evidence of whether or not our related phase 1 hypotheses, developed a priori, are supported. The survey questions used for each domain are shown in Appendix 5.

Inequality between children with and children without learning disability, from the perspective of clinical staff

Comparing staff’s views about the hospital care and treatment of children with and children without LD and their families indicates the areas of practice in which staff perceive inequality (Table 5). The results showed significant differences in staff’s views in relation to children with LD (1) having access to high-quality hospital care that meets their particular needs (RQ1); (2) having access to hospital appointments, investigations and treatments (RQ2); (3) being involved as active partners in their treatment, care and services (RQ3); and (4) being safe (RQ4), indicating perceived inequality for children with LD in response to each of our RQs. The only exception was staff perceptions about staff relying on parents too much, which showed no difference between the two groups. However, community staff did perceive there to be a difference, feeling that parents of children with LD were relied on too much by staff, compared with parents of children without LD.

| RQ | Individual questions | Children with LD (%) | Children without LD (%) | Statistics | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (SA) | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 (SD) | 1 (SA) | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 (SD) | |||

| 1. Do children with and children without LD and their families have equal access to high-quality hospital care that meets their particular needs? | Necessary knowledge and skills to meet needs | 21 | 45 | 26 | 6 | 3 | 55 | 36 | 6 | 2 | 1 | z = 22.24; p < 0.001 |

| Necessary training to meet needs | 16 | 36 | 29 | 13 | 6 | 50 | 37 | 9 | 3 | 2 | z = 24.66; p < 0.001 | |

| Routinely have access to necessary resources to meet needs | 7 | 25 | 26 | 22 | 10 | 34 | 46 | 14 | 4 | 2 | z = 27.26; p < 0.001 | |