Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 12/211/69. The contractual start date was in June 2014. The final report began editorial review in February 2019 and was accepted for publication in June 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Christopher G Owen reports that he is an active member of the Public Health Research (PHR) Research Funding Committee (16 June 2015 to present). Steven Cummins was a member of the PHR Research Funding Board (13 May 2009 to 12 May 2015). Diabetes mellitus and obesity prevention research at St George’s, University of London is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) South London. Bina Ram was supported by a St George’s, University of London, PhD Studentship. Anne Ellaway is funded by the UK Medical Research Council as part of the Neighbourhoods and Communities Programme (MC_UU_12017–10). Billie Giles-Corti is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Principal Research Fellowship (#1107672). Ashley R Cooper and Angie S Page are supported by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at the University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Bristol.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Owen et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background to the ENABLE London study

Importance of physical inactivity

Physical inactivity is one of the leading causes of premature mortality, responsible for over 5 million deaths per year worldwide. 1 Low levels of physical activity are associated with numerous adverse health outcomes in adulthood, including coronary heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes mellitus and cancers. 2 The annual global health-care cost of physical inactivity has been estimated to be near $54B. 3 In the UK, physical activity levels are undesirably low, with over one-third of men and 40% of women not meeting physical activity recommendations of at least 150 minutes of moderate activity per week. 4 The important need to address this has resulted in initiatives to increase population levels of physical activity, which have become enshrined within public health policy. 5,6 Evidence suggests that levels of physical activity are lowest among those who are socioeconomically disadvantaged7 and those who experience greater economic, access and health-related barriers to being physically active,8 which potentially drives social inequalities. Socioeconomic status is also associated with differences in the types of physical activity observed; in particular, higher socioeconomic status is associated with more vigorous leisure-time physical activity. 9 Previous research has found variation in physical activity by day of the week, with studies showing lower levels of activity on Sundays than weekdays in young adults10 and parents and their children. 11

Housing tenure

There is emerging evidence, from UK-based studies12,13 in particular, suggesting that housing tenure (owner vs. private renter vs. public sector renter) may be an important determinant of health. Among particular groups, including those who are economically inactive or unemployed, housing tenure might provide a better indication of socioeconomic status than measures based on occupation or income. 14 Indeed, in several studies housing tenure remained associated with health outcomes following adjustment for conventional measures of socioeconomic status, such as income or education. 12,15 A more nuanced approach is therefore required with respect to measures of socioeconomic status, and they should not be simply regarded as interchangeable. 13,16 Despite this, there has been limited research examining the direct effect of housing tenure on physical activity, and existing evidence is equivocal. Harrison et al. 17 found no association between housing tenure and meeting the recommended levels of physical activity among community-dwelling healthy adults in the north-east of England. 17 Similarly, housing tenure was not associated with self-reported energetic physical activity among older Australians. 18 Ogilvie et al. 19 found overall levels of physical activity to be higher in individuals living in social housing than in owner-occupiers. 19 The authors suggest that social housing tenure may capture occupational physical activity levels that are likely to be higher among those in social housing. 19 By contrast, living in private-rented accommodation was associated with a greater likelihood of taking up exercise over a 9-year period among men aged 18–49 years at baseline than living in local authority accommodation. 20

The residential built environment

Housing tenure may affect health and health behaviours in part through characteristics of the home or the neighbourhood itself,21,22 or through psychological factors such as self-efficacy or self-esteem. 23 Social housing estates, which are common in the UK, may be associated with specific cultures and norms, which in turn shape residents’ behaviours. 12 Subjective characteristics of the neighbourhood environment, such as higher perceived access to recreational facilities and shops in local proximity, have been shown to be associated with higher levels of physical activity. 24,25 Residents who perceive their neighbourhood more positively have been shown to have better mental health and are less likely to relocate. 26 Conversely, real and perceived crime has the potential to constrain residents’ physical activity. 27 However, a recent systematic review suggested a lack of association between physical activity and perceptions of safety from crime; this highlights the need for high-quality evidence, including prospective studies and natural experiments,28 to examine this issue further. In particular, high-quality evidence is needed to understand the potentially multifactorial influence of residential location on health and health behaviours, with effects that are likely to extend beyond simple measures of socioeconomic status. 28

Dose–response meta-analyses suggest that even small increases in physical activity would confer significant health benefits, particularly for cardiovascular and diabetes mellitus-related outcomes. 2 Increasing physical activity levels, particularly among those living in more disadvantaged neighbourhoods, is an important public health priority. However, a wide range of community-wide interventions to increase population levels of physical activity, particularly those associated with change in the residential built environment, have failed to show consistently beneficial effects. 29 Moreover, where modest effects have been shown, there is very little evidence and persistence of effects is not routinely assessed. 29 Despite this, community-wide interventions related to the built environment remain attractive given their population reach.

Physical activity and the built environment

There is growing literature that investigates the influence of the built environment on physical activity levels. 30 It seems highly plausible that improved walkability and improved access to green space, public transport and recreational facilities would encourage increased physical activity. 31 However, evidence is heavily reliant on cross-sectional studies,32 which are prone to selection bias, in which people who are living in less walkable neighbourhoods are often intrinsically different from those who are not. Such studies make it difficult to establish temporality or to infer causal effects. 33 Moreover, evidence has been mixed showing built environment-related associations with adiposity, but not with physical activity, which suggests that other health behaviours might be affected. 34,35 Longitudinal studies have sought to establish causal associations of physical activity and the built environment, but the number of studies are few and the systematic reviews of studies, to date, have found this evidence less convincing. 29,33,36 Specific methodological weaknesses have included (1) comparing movers with non-movers, who may be inherently different and have different reasons for moving or staying that govern their physical activity patterns,33 and (2) often relying on self-reported physical activity, which is prone to measurement error and reporting bias,37 and which could have an appreciable impact on the reporting of health outcomes at a population level. 38 There have been increasing calls for high-quality evidence, particularly natural experiments, to evaluate the effect of the built environment on health behaviours, specifically physical activity levels, in which the population effects of sizeable change in the built environment can be examined. 39–41 However, there have been limited opportunities to carry out such studies.

The ENABLE London study

The Examining Neighbourhood Activities in Built Living Environments in London (ENABLE London) study takes advantage of the natural experiment provided by the rapid change of brown-field land in the London Borough of Newham, UK, to create a novel built environment for public use and occupancy (namely ‘East Village’ E20, formerly the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games Athletes’ Village). The extensive features of East Village, which make this sizeable change in the built environment suitable for evaluation as an intervention, are outlined below.

The East Village ‘intervention’

The planned intervention was the mixed-use development of the East Village residential neighbourhood incorporating commercial, retail, educational and transportation resources.

Specific activity-permissive features designed to encourage physical activity include improved access to open land and parkland, unrivalled transport links, and active travel options (including extensive walking and cycling paths), design features of the local environment (such as street furniture, provision and arrangement of pedestrianised space, public space aesthetics, secure bicycle parking) and the provision of new formal cycling and walking facilities in the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, such as the VeloPark, and cycle paths that extend into the Lee Valley and connect to the London Cycle Network. 42,43 A local school, Chobham Academy, is within walking distance and provides schooling for all 3- to 19-year-olds. Retail outlets were planned within easy walking distance for everyday use (creating plazas at ground level within dedicated areas of East Village). 42,43 Moreover, East Village is in close proximity to Westfield Stratford City – Europe’s largest urban shopping centre. Restriction of resident car parking (where fewer than one-sixth of homes have a designated parking space) combined with improved public transport links is designed to encourage local residents to adopt active modes of transport. 42,43

Accommodation and housing tenures in East Village

East Village consists of 2818 units of accommodation, of which 1379 are social and intermediate accommodation (including shared ownership, shared equity and affordable market-rent), and 1439 are for market rent (private rent). The housing development includes a mixture of one- to four-bedroom town houses and apartments designed for single occupancy through to family-sized accommodation. Details of the different housing types are given below:

-

Social housing – approximately 675 units were available to those on the social housing register. The social housing sector is managed by East Thames Group and Triathlon Homes housing associations.

-

Intermediate accommodation – owned by Triathlon Homes (in association with the East Thames Group) with a total of 704 units (a mix of 79 shared ownership units, 269 shared equity units and 356 affordable market-rent units).

-

Market-rent accommodation – 1439 units owned by Get Living London for private rent.

Main research questions

The ENABLE London study sought to address the following primary research question: do those living in social, intermediate and market-rent accommodation in East Village show a sustained change in their physical activity levels, compared with their levels before moving into the Village, and compared with physical activity change among those who did not move into East Village?

Specific objectives of the study were to examine:

-

Whether or not any increase in physical activity observed among those living in East Village is directly attributable to the use of their local built environment and, if so, which facilities (e.g. open spaces, cycle paths, pedestrian walkways, recreational or green space, sporting venues) are important.

-

Whether or not changes in physical activity patterns in those living in East Village are modified by other factors, including age, sex, ethnicity, proximity to facilities, associated with living in East Village, housing tenure (as a marker of socioeconomic status) and employment status.

-

Whether or not adiposity levels among those living in East Village show a change from levels before moving into East Village, compared with any changes observed among those who did not move to East Village over the same period.

-

If changes in adiposity levels were observed, whether or not, and to what extent, changes in adiposity over the study period reflect changes in physical activity.

Secondary research questions included:

-

Does moving to East Village improve levels of mental health (depression and anxiety) and well-being, compared with those who did not move?

-

Does moving to East Village improve measures of the built environment and neighbourhood perceptions before and after moving, compared with those who remained outside East Village throughout?

This report

This report presents an original detailed description and summary of a large body of research, some of which has been published, submitted, or is being prepared for publication in other open-access academic journals. Further details of methods and findings presented in this report can be found in these publications, which are (1) cited in the report, (2) listed in Publications and (3) available on the study website (www.enable.sgul.ac.uk). We will continue to keep the study website updated with further publications emanating from the study.

Chapter 2 ENABLE London study methodology

Introduction

This chapter provides a description of the methods used in the ENABLE London study, providing an overview of the research design, participant recruitment and data collection. Key exposure and outcome variables collected during the study are outlined, along with a summary of the quantitative data analysis methods used. Derived variables and detailed analytic approaches used for different aspects of the study are described in each chapter accordingly.

Overall research design

The main aim of the study was to investigate the effect of a major change in the residential built environment, triggered by moving to East Village, an area purposefully planned on active design principles and on the physical activity levels of residents, in particular the levels of walking and cycling. There was also a broader set of research questions that this study sought to examine; importantly, examining change in the objective measures of the built environment associated with moving to East Village, in addition to neighbourhood perceptions of the area, to confirm that the development had the desired effect. Without being able to demonstrate change in the built environment (i.e. the primary exposure), change in health-related outcomes attributable to the built environment could not be expected. Other outcomes included change in travel mode and other health behaviours, including mental health and well-being. The study was originally conceived as a longitudinal study of adults seeking to move into the three housing tenures in East Village, with assessments taking place prior to and after the move. Within the cohort would be a control population: those who were seeking to move but did not move to East Village. The quantitative methods implemented in this study were supported by qualitative methods on a small sample of the cohort to further understand drivers and perceptions of moving to East Village and the potential effects on travel behaviours.

The East Village development was scheduled for occupancy in the summer of 2013. The original research design envisaged baseline measures to be taken from late 2012 to early 2013, and follow-up to be taken 1 year later from late 2013 to early 2014. However, delays to the opening of East Village led to the postponement of advertising the accommodation for occupancy and staggered release of accommodation by housing type, with the first residents of East Village not moving in until 2014. The research design of the study was therefore adapted to accommodate the delays to the opening of East Village and the staggered release of accommodation. With the delays in finalising the development and staged release of accommodation, coupled with the scientific need for 2-year as opposed to 1-year follow-up,44 recruitment and baseline assessments of participants took place from 2013 to 2015, with a 2-year follow-up from 2015 to 2017.

Ethics considerations

Ethics approval for the study was provided by City Road and Hampstead Review Board (Research Ethics Committee reference number 12LO1031).

Study population

The inclusion criteria of the ENABLE London study were families residing in Greater London (largely from East London and the London Borough of Newham) who were seeking to move into social, intermediate and market-rent accommodation in East Village. Participants who moved to East Village at follow-up were directly exposed to the new social and built environment, and its active design features. Participants who were seeking to move to East Village but remained in their place of origin (largely from East London) or moved elsewhere formed the control group. Applicants registering an interest or applying to move into East Village were invited to take part in the study (including at least one adult and one child aged ≥ 8 years to allow accelerometer assessment); a maximum of four family members per household were included. Although the study was aimed at families (i.e. parents and children), working-aged adult-only households were also invited. Households with disabled family members were invited to the study when appropriate, although the primary focus of the study was able-bodied family members. Non-English-speaking families were also approached, using interpreters when applicable.

Socioeconomic position

The inclusion of occupants seeking social, intermediate and market-rent accommodation in East Village (largely based on level of income) allowed inclusion of people from widely different social and ethnic origins, representative of the diverse East London population. This allowed sociodemographic differences in the use of the local area and potential effects on health outcomes to be gauged,5,45 particularly among individuals and households of lower socioeconomic status, who potentially have the most to gain from improvements in the residential built environment. 46

Recruitment

Participants were recruited through the East Thames Group Housing Association (responsible for social housing tenants), Triathlon Homes (intermediate housing: affordable market-rent/shared ownership/shared equity) and Get Living London (market-rent). Prospective tenants went through a rigorous financial process to determine eligibility for accommodation. Those applying to move into East Village social housing were provided with information about the study and invited to take part by East Thames Group representatives directly, whereas the ENABLE London team (in association with Triathlon Homes and Get Living London) invited those from intermediate and market-rent housing sectors.

Data collection

Baseline and 2-year follow-up of study participants was carried out at the participants’ home (or at a location convenient to the participant). Data items collected in the ENABLE London study at baseline and follow-up are listed in Box 1 and summarised below.

Physical activity and location data:

-

ActiGraph GT3X+ accelerometer (ActiGraph LLC, Pensacola, FL, USA) worn over a consecutive 7-day period.

-

QStarz BT-1000XT GPS travel recorder (QStarz International Co, Ltd, Taipei, Taiwan) worn for 1 week.

-

Ordnance Survey AddressBase® Premium versions 2015 and 2017 (Ordnance Survey, Southampton, UK) mapping of place of residence at baseline and 2-year follow-up to provide measures of land use mix, street connectivity, residential density, walkability and connectivity indices (see www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/business-government/products/addressbase-premium; accessed 16 September 2019).

Anthropometry:

-

Height measured to the last complete millimetre (Leicester Stadiometer; Seca, Birmingham, UK).

-

Weight measured to the last complete 0.1 kg using an electronic digital scale, and fat mass (kg), fat-free mass (kg) and muscle mass (kg) measured by leg-to-leg bioimpedance (Tanita SC-240 Body Composition Analyser; Tanita Inc, Tokyo, Japan).

-

Body mass index calculated as weight/height squared in kg/m2.

Questionnaire data:

-

Demographics, including date of birth, gender and ethnicity, of the participant.

-

Number of people living in the household, relationships, type of accommodation, household features (including lifts, stairs, garden), type of tenure, duration at current property, vehicles owned and dog ownership.

-

Qualifications, employment status, and job title of adult participants (based on Census 2011 questions). 45

-

Method of travel to work/place of study and daily commuting times.

-

Household income as either weekly or monthly amounts (based on National Evaluation of Sure Start income questions).

-

Perception of general health, self-report of health problems (based on Census 2011 questions)45 and effects on mobility.

-

Health outcomes including assessments of mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression and overall perception of health on a scale from 0 to 100 [using EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) questions].

-

Satisfaction scores including perception of overall levels of satisfaction, feeling happy and anxious, on a scale from 1 to 10 (based on questions used in the Measuring National Well-being Programme), and further assessment of anxiety and depression based on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

-

Current and previous smoking status, and current alcohol consumption (using Health Survey for England questions47).

-

Perceptions of the local area/neighbourhood, including transport, leisure activities, vandalism, litter, traffic, attractiveness and safety, as well as assessment of social participation, support, cohesion and trust.

-

Type of activities carried out and frequency of carrying out vigorous, moderate, walking, sitting activities in the last 7 days (based on the short-form IPAQ).

-

Cost of activities including membership fees, vouchers received and equipment bought to do physical activity.

-

Attitudes to exercise.

-

Television and computers/screen time assessment.

-

Fruit and vegetable consumption, and usual sleeping times.

IPAQ, International Physical Activity Questionnaire.

Physical activity level/pattern and location

Objectively measured physical activity (daily steps) was the primary outcome and was assessed over a consecutive 7-day period using hip-mounted ActiGraph GT3X+ accelerometers, combined with an assessment of physical activity location using Global Positioning System (GPS) travel recorders (BT-1000XT). Accelerometers provided daily measures of steps and different intensities of activity, including moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) (both overall and in 10-minute bouts, in accordance with UK physical activity recommendations, although levels in bouts were too low to be usefully used in analyses). 5 The approaches to analysing ActiGraph data are detailed in Chapter 3. Simultaneous use of ActiGraph accelerometers and GPS travel recorders allowed active travel components of physical activity (i.e. walking), as well as indoor and outdoor activities, to be identified using methods previously described by the investigators48,49 and the methods detailed in Chapter 5. In addition, GPS data allowed the geographical location at which different levels of physical activity occurred to be identified (from sedentary to vigorous, using established cut-off points in accelerometer data), both at baseline and at follow-up. Together, these measures allowed accelerometry data to be interpreted in depth, allowing the nature and location of recorded activities, particularly active forms of transport such as walking and cycling, to be identified. Moreover, it allowed the contribution of active transport local to place of residence to be quantified and compared between those living in East Village and control areas (see Chapter 5).

Environmental exposures

Geographical information systems (GIS) were used to extract objective data on features of the local environment (see Chapter 4). In combination with ActiGraph and GPS data from study participants, this allowed the location of different levels of physical activity (including both high and low levels of activity) to be accurately identified. This method has been used previously by the investigators to establish the important contribution of walking to school and location (including land use type) to MVPA levels in children. 49,50 A number of data sources were used to identify environmental and activity-permissive features within East Village and control areas, including Ordnance Survey (OS) MasterMap Tomography Layer (versions December 2018, May 2014, June 2015) (Ordnance Survey, URL: www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/business-government/products/mastermap-topography; accessed September 2019), Integrated Transport Network and Transport for London (TfL)51 sources, Olympic Delivery Authority and local authority data, as well as other online resources. In particular, OS data were used to derive indices, such as land use mix, street connectivity, residential density, walkability and connectivity indices, including walking distance to particular features of the built environment, including green space. 52

Anthropometric measurements

Height was measured to the last complete millimetre with a portable stadiometer (Leicester Stadiometer; Seca, Birmingham, UK) at baseline and follow-up. Both weight and leg-to-leg bioimpedance were assessed using an electronic Tanita SC-240 body composition analyser (Tanita Inc., Tokyo, Japan) to provide measures of fat mass (kg) and fat-free mass (kg); body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight/height2 (kg/m2). In total, eight Leicester Stadiometers and Tanita SC-240 body composition analysers were used to measure the participants. The Tanita devices were operated using factory default settings and were regularly checked in accordance with recommended review procedures.

Questionnaire data

Questionnaires were converted into electronic format using SNAP Surveys software (version 11, SNAP Surveys, London, UK), and completed by study participants using dedicated laptops. The questionnaires used established validated methodologies to collect detailed information on patterns and types of activity that were local to the place of residence. In particular, the ‘Neighbourhood Physical Activity Questionnaire’ provided data to examine walking within the neighbourhood,53 and the ‘Neighbourhood Environment Walking Scale’ provided data on perceptions of the neighbourhood environment. 54,55 Information on self-defined ethnic origin (based on the 2011 Census45) and a range of social markers were recorded (including employment status, income, duration and location of work), together with home address and postcode of residence, allowing GIS-determined distance to local amenities to be measured. Questions about general health/health status,45 well-being, anxiety and depression, including both clinical and subclinical forms of assessment suitable for use in community settings, were also used (see Chapter 6). 22,56–58 Physical activity was assessed using an adaptation of the short-form, self-reported International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)59 to provide perceived levels of physical activity in addition to objective measures. Adults were asked about their attitudes to physical activities (including both sedentary, such as screen time, and physically active forms) and factors that influence their physical activity behaviour. Participants were asked about perceived personal, social and environmental influences on physical activity, their use of recreational space (particularly walkways and cycle paths) and facilities in their residential neighbourhood (including costs incurred). Participants were also asked about the availability, accessibility (method of travel and journey times) and usage of local amenities (walkways, cycle paths, parks, swimming pools, etc.); their perceptions of the safety of these amenities and the degree to which they permit their child independent or supervised use were also elicited. The questionnaire also included sections to ascertain levels of social participation, support, cohesion and trust. 60 These items were particularly relevant to gauge how the use and perceptions of the local area by others had an impact on individual use and how this might differ from objectively measured features of their neighbourhood. The main questionnaire is included in Appendix 1. Questions were repeated at follow-up, but further questions were included to capture use and frequency of use of the Olympic Park and shopping facilities in the East Village area. Additionally, given the 2-year follow-up, a further question was included to establish whether or not participants had ever lived in East Village between baseline and follow-up interviews.

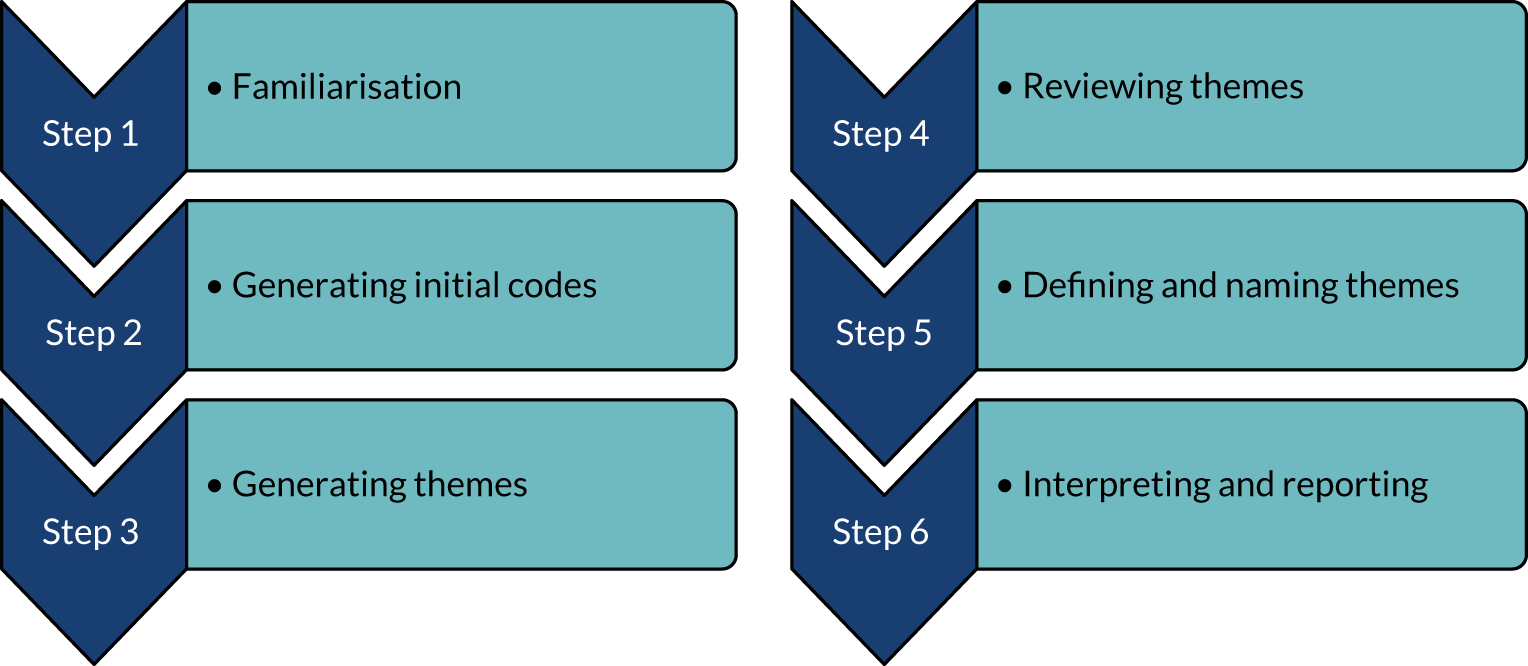

Qualitative data

In addition to the rich quantitative data, focus groups among study participants in the social housing sector, who were the first to move into East Village, were carried out to identify issues of importance, particularly about perceptions and use of their local environment, and to confirm whether or not the ENABLE London study questionnaire was capturing a suitable and accurate insight of constructs that would identify environmental factors influencing health behaviour (see Chapter 7). GIS and GPS data were also combined with qualitative spatial narratives among study participants to explore differences in active travel associated with moving to East Village. These narratives used individual participant maps to assess how the built environment influences travel behaviour and physical activity: examining change in travel patterns, reasons for the change, purpose of travel and choice of route (see Chapter 8).

Sample recruited and examined

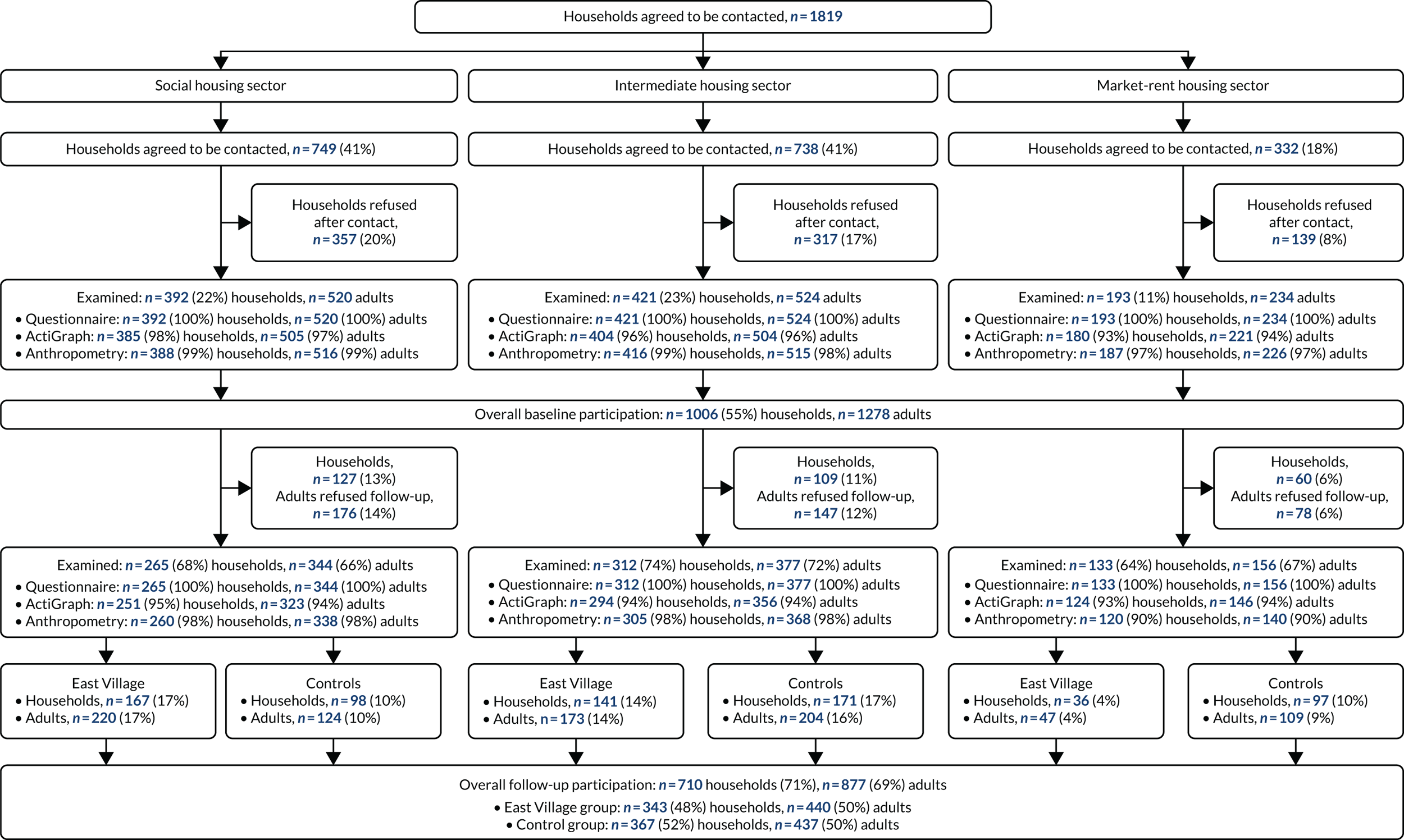

A total of 1819 households (749 social, 738 intermediate and 332 market-rent) expressed an interest in taking part in the study, of which 1006 (392 social, 421 intermediate and 193 market-rent) were examined at baseline from January 2013 to January 2016 (Figure 1). More than one person per household was invited to take part. In total, 1497 individuals took part: 1278 adults (520 social, 524 intermediate and 234 market-rent) and 219 children (209 social, eight intermediate and two market-rent). Figure 2 shows the geographic home locations of study participants at baseline, which highlights the Newham focus of those in social housing, and Greater London geographic diversity of participants seeking intermediate and market-rent accommodation. The small number of children recruited was not expected given that the accommodation in East Village was largely designed for family occupation. Most of the children recruited (95%) were from the social housing sector, and very few children were recruited from intermediate and market-rent groups, which were largely adult-only households. The overall number of children was too small to provide sufficient power to detect change in physical activity; therefore, only adults were considered from here on. The smaller number of adult participants recruited from the market-rent sector reflected the limitations placed on the extent and duration of access to applicants seeking this type of accommodation in East Village. The ENABLE London cohort was predicated on recruiting 1200 adults from 1200 households and succeeded in recruiting 1278 adults from 1006 households. Given the modest imbalance between movers and non-movers, the compliance and the follow-up rate observed, the study was powered to detect a 750-step change [0.3 standard deviation (SD)] at 90% power and with a probability of 0.01 among those who move to East Village. 61

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of households and participants examined at baseline and follow-up in the ENABLE London study. Reproduced from Ram et al. 61 Published by the BMJ Publishing Group Limited. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

FIGURE 2.

Baseline locations of social, intermediate and market-rent households participating in the ENABLE London study. Reproduced from Ram et al. 61 Published by the BMJ Publishing Group Limited. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

The characteristics of the baseline sample by housing sector are summarised in Table 1. Participants seeking social housing in East Village were older, mainly female, and more likely to be from ethnic minority groups than the intermediate and market-rent sectors. The social housing sector was largely residing in households of four or more people (58% vs. intermediate 29% and market-rent 27%), which included children (82% vs. intermediate 18% and market-rent 10%). Only one-quarter (24%) of the social housing sector had a degree qualification compared with 82% of intermediate and 80% of market-rent participants. Half of the social housing sector were employed, compared with 94% of the intermediate and 87% of the market-rent participants. There were also social gradients in the type of employment, with 12% of the social housing sector participants in higher managerial or professional occupations compared with 72% of the intermediate sector participants and 66% of the market-rent sector participants. Fewer participants in the social housing sector reported very good or good overall health (76%) than did intermediate (88%) and market-rent (91%) participants.

| Characteristic | All housing sectors, n (%) | Housing sector,a n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social housing | Intermediate | Market-rent | ||

| Cohort | ||||

| Participants | ||||

| Households | 1006 (100) | 392 (52) | 421 (57) | 193 (58) |

| Adults | 1278 (100) | 520 (41) | 524 (41) | 234 (18) |

| Individual characteristics | ||||

| Age, median (IQR) | ||||

| Age | 31 (26–40) | 37 (27–44) | 30 (26–35) | 28 (24–33) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 547 (43) | 141 (27) | 275 (52) | 131 (56) |

| Female | 731 (57) | 379 (73) | 249 (48) | 103 (44) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 617 (48) | 96 (18) | 358 (68) | 163 (70) |

| Asian | 214 (17) | 108 (21) | 77 (15) | 29 (12) |

| Black | 323 (25) | 251 (48) | 55 (11) | 17 (7) |

| Mixed/other | 124 (10) | 65 (13) | 34 (6) | 25 (11) |

| Household-level characteristics | ||||

| Household composition | ||||

| 1 person | 97 (8) | 28 (5) | 38 (7) | 31 (13) |

| 2 people | 385 (30) | 88 (17) | 217 (41) | 80 (34) |

| 3 people | 278 (22) | 101 (19) | 116 (22) | 61 (26) |

| ≥ 4 people | 518 (41) | 303 (58) | 153 (29) | 62 (27) |

| Living with partner | ||||

| Yes | 556 (44) | 202 (39) | 261 (50) | 93 (40) |

| No | 615 (48) | 244 (47) | 245 (47) | 126 (54) |

| Unknown | 107 (8) | 74 (14) | 18 (3) | 15 (6) |

| Living with children | ||||

| Yes | 542 (42) | 425 (82) | 93 (18) | 24 (10) |

| No | 736 (58) | 95 (18) | 431 (82) | 210 (90) |

| Socioeconomic characteristics | ||||

| Educationb | ||||

| Degree or equivalent/higher | 736 (58) | 122 (24) | 428 (82) | 186 (80) |

| Intermediate qualification | 380 (30) | 280 (54) | 70 (13) | 30 (13) |

| Other/none | 159 (12) | 117 (23) | 25 (5) | 17 (7) |

| Employment statusc | ||||

| Employed | 948 (74) | 252 (49) | 492 (94) | 204 (87) |

| Unemployed | 91 (7) | 73 (12) | 7 (1) | 11 (5) |

| Economically inactive | 236 (18) | 192 (37) | 25 (5) | 19 (8) |

| NS-SECd | ||||

| Higher managerial/professional | 591 (46) | 61 (12) | 375 (72) | 155 (66) |

| Intermediate occupations | 179 (14) | 62 (12) | 79 (15) | 38 (16) |

| Routine/manual | 170 (13) | 125 (24) | 34 (6) | 11 (5) |

| Health characteristics | ||||

| General health status | ||||

| Very good | 365 (29) | 140 (27) | 153 (29) | 72 (31) |

| Good | 703 (55) | 253 (49) | 310 (59) | 140 (60) |

| Fair | 179 (14) | 103 (20) | 58 (11) | 18 (8) |

| Bad | 25 (2) | 19 (4) | 2 (0.4) | 4 (2) |

| Very bad | 6 (0.5) | 5 (1) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (–) |

| Limiting longstanding illness | ||||

| Yes | 162 (13) | 107 (21) | 41 (8) | 14 (6) |

| Physical activitye | ||||

| Daily steps, mean (SD) | 8950 (3190) | 7803 (3303) | 9684 (2924) | 9337 (2990) |

| MVPA (minutes/day), mean (SD) | 60 (26) | 50 (26) | 65 (23) | 65 (25) |

| MVPA in 10-minute boutsf | 15 (6–30) | 7 (1–15) | 21 (10–34) | 21 (21–36) |

| Anthropometry | ||||

| Height (m), mean (SD) | 1.69 (0.10) | 1.65 (0.09) | 1.71 (0.10) | 1.72 (0.10) |

| Weight (kg)f | 71 (62–82) | 71 (63–84) | 71 (62–81) | 73 (61–80) |

| BMI (kg/m2)f | 25 (22–28) | 26.3 (23–31) | 24 (22–27) | 24 (22–26) |

| Fat mass (kg)f,g | 18 (13–26) | 23 (16–31) | 15 (11–21) | 15 (11–21) |

| Mental health | ||||

| Depressionh | 173 (14) | 100 (21) | 52 (10) | 21 (9) |

| Anxietyh | 392 (31) | 169 (33) | 146 (28) | 77 (33) |

| Well-being | ||||

| Low levels of life satisfactioni | 330 (26) | 169 (33) | 117 (22) | 44 (19) |

| Low levels of feeling that life is worthwhilei | 265 (21) | 123 (24) | 95 (18) | 47 (20) |

| Low levels of feeling happyi | 358 (28) | 157 (30) | 130 (25) | 71 (30) |

| Neighbourhood perceptionsj | ||||

| Crime-free, mean (SD) | 2.03 (4.40) | 0.69 (4.59) | 2.94 (3.96) | 2.95 (4.18) |

| Quality, mean (SD) | 3.52 (4.53) | 2.41 (4.58) | 4.36 (4.41) | 4.13 (4.20) |

Follow-up participation rates

Of the 1278 adult participants from 1006 households examined at baseline, 877 (69%) adults from 710 (71%) households were examined at follow-up (see Figure 1). A total of 401 adult participants seen at baseline were not followed up.

Social housing sector

Social housing sector participants were followed up between February 2015 and September 2016. Of 520 adult participants from 392 households examined at baseline in the social housing sector, 66% (n = 344) of adult participants from 265 (68%) households were examined at follow-up. Overall, the social housing sector represented 39% (n = 344/877) of the adults seen at follow-up and 37% (n = 265/710) of households.

Intermediate housing sector

Follow-up examinations of the intermediate housing sector took place between July 2015 and September 2017. Among the 524 adults from 421 households examined at baseline, 72% (n = 377) from 312 (74%) households were examined at follow-up. The intermediate sector represented 43% (n = 377/877) of adults and 44% (n = 312/710) of households.

Market-rent housing sector

Market-rent participants were followed up between January 2016 and October 2017. Of 234 adults from 193 households examined at baseline, 67% (n = 156/234) of adults from 133 (69%) households were examined at follow-up. The market-rent sector represented 18% (n = 156/877) of the adults, and 19% (n = 133/710) of households seen at follow-up.

Follow-up rates by East Village and control groups

Half of the adult participants (50%, n = 441/877) had moved to East Village at follow-up and half had not; the participants who had not moved formed the control group (see Figure 1). Of the 441 adult participants who moved to East Village at follow-up, 50% were from the social housing sector, 39% were seeking intermediate accommodation and 11% were seeking market-rent accommodation. Within the control group (n = 436 adults), 28% were social housing participants, 47% were intermediate participants and 25% were market-rent participants. Among the social housing sector, participants in the East Village group had a similar sociodemographic profile to those in the control group. No differences were observed in the following characteristics: age, sex, household composition, living with partner, living with children, education, employment status, socioeconomic status [(National Statistics Socioeconomic Classification (NS-SEC)] and limiting longstanding illness (LLI) (Table 2). However, there were marked differences in ethnicity between East Village and control groups (p < 0.001), with a higher proportion of black ethnic participants in the East Village group than in the control group (55% and 32%, respectively), and a lower proportion of Asian participants in the East Village group than in the control groups (14% and 38%, respectively) in the social housing sector. For intermediate participants, the East Village and control groups were similar in household composition, living with partner, qualifications and NS-SEC, but there were differences in age between East Village and control groups (p < 0.001), sex (p = 0.02), ethnicity (p < 0.001), living with children (p = 0.004), employment status (p = 0.02), and LLI (p = 0.004). The intermediate participants in the East Village group were younger, less likely to be female and living with children, and reported a LLI, and were more likely to be of white ethnicity, employed and in intermediate occupations than the control group (see Table 2). Market-rent participants in the East Village and control groups were similar in their baseline sociodemographic profile, with little difference observed. Differences in baseline physical activity levels, anthropometry, neighbourhood perceptions, mental health and well-being outcomes, and the analytic approach used for respective outcomes, are outlined in Chapters 3–6.

| Characteristic | All housing sectors (N = 877) | Housing sector | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social (N = 344) | Intermediate (N = 377) | Market rent (N = 156) | ||||||||||

| East Village (N = 441), n (%) | Control (N = 436), n (%) | p-value | East Village (N = 220), n (%) | Control (N = 124), n (%) | p-value | East Village (N = 174), n (%) | Control (N = 203), n (%) | p-value | East Village (N = 47), n (%) | Control (N = 109), n (%) | p-value | |

| Individual characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Age group (years) | ||||||||||||

| 16–24 | 104 (24) | 75 (17) | 47 (21) | 18 (15) | 38 (22) | 30 (15) | 19 (40) | 27 (25) | ||||

| 25–34 | 194 (44) | 185 (42) | 61 (28) | 32 (26) | 113 (65) | 100 (49) | 20 (43) | 53 (49) | ||||

| 35–49 | 123 (28) | 138 (32) | 95 (43) | 66 (53) | 22 (13) | 61 (30) | 6 (13) | 11 (10) | ||||

| ≥ 50 | 20 (5) | 38 (9) | 0.01a | 17 (8) | 8 (6) | 0.27a | 1 (1) | 12 (6) | < 0.001a | 2 (4) | 18 (17) | 0.07a |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Female | 247 (56) | 248 (57) | 0.80a | 158 (72) | 91 (73) | 0.76a | 70 (40) | 107 (53) | 0.02a | 19 (40) | 50 (40) | 0.53a |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| White | 212 (48) | 225 (51) | 38 (17) | 25 (20) | 139 (80) | 122 (60) | 35 (74) | 78 (72) | ||||

| Asian | 56 (13) | 91 (21) | 31 (14) | 47 (38) | 18 (10) | 35 (17) | 7 (15) | 9 (8) | ||||

| Black | 131 (30) | 81 (19) | 120 (55) | 40 (32) | 9 (5) | 32 (16) | 2 (4) | 9 (8) | ||||

| Mixed/other | 42 (10) | 39 (9) | < 0.001a | 31 (14) | 12 (10) | < 0.001a | 8 (5) | 14 (7) | < 0.001a | 3 (6) | 13 (12) | 0.42b |

| Household characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Household composition | ||||||||||||

| 1 person | 30 (7) | 54 (12) | 14 (6) | 25 (4) | 9 (5) | 17 (8) | 7 (15) | 12 (11) | ||||

| 2 people | 127 (29) | 174 (40) | 33 (15) | 47 (16) | 76 (44) | 82 (40) | 18 (38) | 45 (41) | ||||

| 3 people | 94 (21) | 121 (28) | 45 (20) | 40 (13) | 38 (22) | 52 (26) | 11 (23) | 29 (27) | ||||

| ≥ 4 people | 190 (43) | 87 (20) | 0.20a | 128 (58) | 12 (67) | 0.22a | 51 (29) | 52 (26) | 0.45a | 11 (23) | 23 (21) | 0.88a |

| Living with partner | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 186 (42) | 210 (48) | 84 (38) | 60 (55) | 82 (47) | 101 (50) | 20 (43) | 49 (45) | ||||

| No | 215 (49) | 205 (47) | 103 (47) | 50 (46) | 88 (51) | 96 (47) | 24 (51) | 59 (54) | ||||

| Unknown | 40 (9) | 21 (5) | 0.02a | 33 (15) | 14 (13) | 0.17a | 4 (2) | 6 (3) | 0.79b | 3 (6) | 1 (1) | 0.17b |

| Living with children | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 206 (47) | 172 (39) | 0.03a | 177 (20) | 109 (12) | 0.08a | 24 (14) | 52 (26) | 0.004a | 5 (11) | 11 (10) | 0.92a |

| Socioeconomic characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Educationc | ||||||||||||

| Degree or equivalent/higher | 249 (57) | 287 (66) | 55 (25) | 34 (27) | 154 (89) | 166 (82) | 40 (85) | 87 (80) | ||||

| Intermediate qualification | 137 (31) | 102 (23) | 118 (54) | 59 (48) | 15 (9) | 26 (13) | 4 (9) | 17 (16) | ||||

| Other/none | 55 (13) | 45 (10) | 0.01a | 47 (21) | 30 (24) | 0.60a | 5 (3) | 11 (5) | 0.18a | 3 (6) | 4 (4) | 0.39b |

| Employment statusd | ||||||||||||

| Employed | 307 (70) | 347 (80) | 98 (45) | 67 (54) | 169 (97) | 183 (90) | 40 (85) | 97 (89) | ||||

| Unemployed | 36 (8) | 22 (5) | 33 (15) | 12 (10) | 1 (1) | 4 (2) | 2 (4) | 6 (6) | ||||

| Economically inactive | 97 (22) | 67 (15) | 0.004a | 88 (40) | 45 (36) | 0.18a | 4 (2) | 16 (8) | 0.02b | 5 (11) | 6 (6) | 0.51b |

| NS-SECe | ||||||||||||

| Higher managerial/professional | 179 (41) | 246 (56) | 23 (24) | 24 (36) | 124 (74) | 146 (81) | 32 (80) | 76 (78) | ||||

| Intermediate occupations | 69 (16) | 54 (12) | 27 (28) | 16 (24) | 34 (20) | 22 (12) | 8 (20) | 16 (16) | ||||

| Routine/manual | 56 (13) | 44 (10) | 0.003a | 46 (48) | 26 (39) | 0.23a | 10 (10) | 13 (7) | 0.12a | 0 (0) | 5 (5) | 0.43b |

| Health characteristics | ||||||||||||

| General health status | ||||||||||||

| Very good | 134 (30) | 112 (26) | 65 (30) | 27 (22) | 52 (30) | 52 (26) | 17 (36) | 33 (30) | ||||

| Good | 234 (53) | 253 (58) | 101 (46) | 61 (49) | 107 (61) | 125 (62) | 26 (55) | 67 (61) | ||||

| Fair | 63 (14) | 59 (14) | 45 (20) | 28 (23) | 15 (9) | 24 (12) | 3 (6) | 7 (6) | ||||

| Bad | 8 (2) | 12 (3) | 7 (3) | 8 (6) | 0 (–) | 2 (1) | 1 (2) | 2 (2) | ||||

| Very bad | 2 (1) | 0 (–) | 0.23a | 2 (1) | 0 (–) | 0.27a | 0 (–) | 0 (–) | 0.35 | 0 (–) | 0 (–) | 0.90 |

| LLI | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 58 (13) | 59 (14) | 0.87a | 49 (22) | 28 (23) | 0.95a | 6 (3) | 23 (11) | 0.004a | 3 (6) | 8 (7) | 1.00b |

Conclusions

The ENABLE London cohort provides a unique opportunity to examine the impact of a major and focused change in the urban built environment, associated with the rapid repurposed East Village development after the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games, on the physical activity patterns and other health-related behaviours of the local population, particularly those from less privileged backgrounds. It provides an important test of principle that the built environment can alter health behaviours and health outcomes. If this is shown to be the case, the results will inform evidence-based urban planning in the future, and the way in which environmental changes have an impact on health inequalities.

Chapter 3 Physical activity and adiposity: baseline and 2-year follow-up findings from the ENABLE London study

Introduction

The ENABLE London is a longitudinal study evaluating how active urban design influences the health and well-being of people moving into the former London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games Athletes’ Village, now known as ‘East Village’. 61 East Village is a purpose-built, mixed-use, high-rise residential development, specifically designed to encourage healthy active living by improving walkability and access to public transport, which consists of a mix of social housing, intermediate (including affordable rent, shared ownership and shared equity) housing, and market-rent housing. 61 This chapter draws on baseline data (prior to any potential move to East Village) to:

-

examine predictors of physical activity and adiposity (measured objectively using accelerometry and bioelectrical impedance), including the housing tenure being sought and participants’ perceptions of their neighbourhood

-

examine whether or not physical activity patterns over 7 days vary by housing sector

-

examine whether or not adjustment for perceptions of the neighbourhood environment reduce housing sector differences in physical activity and adiposity.

Given the longitudinal design, the study also provides a unique opportunity to:

-

examine change in objectively measured physical activity and adiposity after 2 years among those who moved to East Village compared with those who did not, which will add robust evidence to the debate about the effect of the built environment on health.

The study was also able to:

-

objectively quantify the quality of the built environment in which people lived among those followed up at both time points using GIS-derived methods

-

gauge the change in neighbourhood perceptions associated with moving to East Village.

Methods

Participants

Examining Neighbourhood Activities in Built Living Environments in London (ENABLE London) study participants were recruited from those seeking or who had applied for new accommodation in East Village. There were three types of housing tenure being sought based on level of income: social (provided by the local authority or housing association at subsidised rates), intermediate (a mixture of shared ownership, shared equity and affordable rent) and market-rent. The inclusion criteria was broad and included anyone interested/applying for single or multiple occupancy accommodation in East Village. There was no explicit exclusion criteria; adults of any age, gender, ethnic group, with or without handicap, were invited to participate. Current housing status was strongly linked to aspirational housing status; those seeking social accommodation were currently in social housing or on social housing waiting lists, and those seeking intermediate and market-rent accommodation were largely in privately rented housing. Aspirational housing tenure is integral to the design of ENABLE London, and we have shown that this provides a clear socioeconomic marker of study participants. For example, those seeking social housing in East Village are more likely to be unemployed, less educated and more likely to represent ethnic minorities (a classic marker of socioeconomic vulnerability), compared with those seeking affordable and market-rent accommodation (see Chapter 2). 61 We have also shown key differences in mental health and well-being between housing sectors; those seeking social housing were more likely to be depressed, anxious and have poorer well-being than other housing sectors (see Chapter 6). 64 Moreover, this is entirely consistent with earlier studies that found both current housing tenure and aspirational housing tenure are associated with a variety of health outcomes, including mental health and measures of general health. 21,65

Assessments of participants were carried out in their place of residence before any potential move to East Village, and 2 years later (February 2015 to October 2017) for those who had moved to East Village, moved elsewhere or not moved. 66

Measures

Physical activity

Participants wore a hip-mounted ActiGraph GT3X+ accelerometer during waking hours over a period of 7 days. Accelerometers provided daily measures of steps (primary outcome), time spent in moderate or vigorous physical activity and time spent sedentary, using established thresholds [sedentary < 100 counts per minute (CPM), moderate physical activity ≥ 1952 CPM]. 67 Periods of non-wear time were defined as ≥ 60 minutes of zero values, allowing for a 2-minute spike tolerance, to provide daily wear time. We excluded days of accelerometer data where the registered wear time was < 540 minutes. Participants with at least 1 day of data were included in the baseline analysis; those with at least 1 day of data at both baseline and follow-up were retained in the longitudinal analysis. We have previously used at least 1 day of 540 minutes (9 hours) of registered time to represent a satisfactory recording of daily activity in a randomised controlled trial of older but overlapping age groups. 68 The at least 1 day of 540 minutes cut-off point was chosen to lessen attrition bias, and was used in this study to maximise inclusion of hard to reach groups, that is those from social housing, who notoriously comply less and recorded less physical activity data.

Adiposity

The protocol for body size and adiposity measurement was identical at baseline and at follow-up. Height was measured to the last complete millimetre using a portable stadiometer. A Tanita SC-240 Body Composition Analyser was used to measure weight to the nearest kilogram and leg-to-leg bioelectrical impedance, from which fat-free mass and fat mass were estimated. BMI was calculated as weight (kg)/height (m)2 and percentage fat mass was calculated as 100 × fat mass (kg)/weight (kg).

Covariates

A team of trained fieldworkers administered self-completion questionnaires using a laptop during home visits (see Table 1). Age, sex, self-defined ethnicity, work status and occupation, and whether or not the participant had a LLI or disability (lasting or expected to last at least 12 months) were collected via a questionnaire. Participants were defined as ‘white’, ‘Asian’, ‘black’, ‘mixed’ or ‘other’; the last two categories were combined in the analysis. Occupation-based socioeconomic status was coded using the NS-SEC to categorise participants into ‘higher managerial or professional occupations’, ‘intermediate occupations’ and ‘routine or manual occupations’. 63 An additional ‘economically inactive’ category included those seeking employment, those unable to work owing to disability or illness, those who were retired, those looking after home and family, and students. We sought information on educational attainment; participants were categorised into ‘degree or equivalent/higher’, ‘intermediate qualifications’ (including A levels and General Certificates of Secondary Education), and ‘other/none’ (including work-based or foreign qualifications).

Built environment variables

Residential built environment characteristics were derived using GIS data at baseline and at follow-up for those households in the Greater London area. These included network distance from home to the closest park (using data from the London Development Database),69 public transport access,51 and measures of neighbourhood walkability, land use mix, residential density and street connectivity computed within a 1-km street network home-centred buffer (see Chapter 4).

Neighbourhood perceptions

Participants completed questionnaires assessing neighbourhood perceptions; the methods used are outlined further in Chapter 6. 64 In brief, five items assessed perceived crime (e.g. ‘There is a lot of crime in my neighbourhood’; Cronbach’s α = 0.87) and six items assessed neighbourhood quality (e.g. ‘This area is a place I enjoy living in’; Cronbach’s α = 0.78). Responses on items were summed and scores ranged from –10 to +10 for perceived crime and –12 to +12 for perceived quality, such that positive scores indicate less perceived crime and better neighbourhood quality whereas negative scores indicate more perceived crime and poorer quality. The scales were derived following an exploratory factor analysis of 14 questions regarding the neighbourhood (see Report Supplementary Material 1). Two neighbourhood perception scores, measuring crime-free neighbourhood (i.e. vandalism, feeling unsafe to walk in neighbourhood, presence of threatening groups) and neighbourhood quality (i.e. accessible features, attractiveness and enjoyment of living in neighbourhood), were derived at baseline using exploratory factor analysis on 14 neighbourhood perception items in the questionnaire,64 and the same items were used to obtain scores at follow-up.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were carried out using Stata® Special Edition version 15 for Windows® (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

To obtain average physical activity variables, we fitted a multilevel linear model for each outcome to allow for repeated measurements of daily physical activity, by fitting participant as a random effect and adjusting for day of the week, day order of recording and month as fixed effects. Raw level one residuals were obtained from the model and a within-person average value of each outcome variable was obtained by averaging these raw residuals. The average of these raw residuals for each participant was added to the sample mean for that particular physical variable to derive an unbiased average level of each physical activity variable at baseline and at follow-up for each person.

Baseline analyses

Physical activity and adiposity outcome variables were inspected for normality; BMI was log-transformed because of its skewed distribution. Multilevel linear regression models were fitted, mutually adjusted for housing sector and participant characteristics (sex, age group, ethnic group and LLI) as fixed effects, with a random effect to allow for household clustering. Age groups (16–24 years, 25–34 years, 35–49 years and ≥ 50 years) were chosen to give a wide spread of ages representative of young adults, young professionals, early middle age and later middle-age/older-age people. Residuals did not show departure from linearity, suggesting that the model assumptions were appropriate. Absolute differences or percentage differences for log-transformed outcomes (i.e. BMI) are presented by sex, age group, ethnic group, LLI and housing sector. Sensitivity analyses examined whether or not associations remained when the sample was restricted to 931 participants (84%) with > 4 days of ≥ 540 minutes per day of recording.

To assess differences in physical activity by day of the week as opposed to overall levels of physical activity, we took the following approach. Daily physical activity data were examined using multilevel models with random effects to allow for multiple days of recording within-person and household clustering. An interaction between housing sector and day of the week was fitted and models were adjusted for sex, age group, ethnic group, LLI, day order of recording and month of measurement as fixed effects.

The associations between neighbourhood perception scales and adiposity and physical activity outcomes at baseline were examined. Each of the neighbourhood quality and crime scores were included in the models as quintiles, to examine the differences in outcomes between the top and bottom quintile. The effect of adjustment for neighbourhood perception on differences in the adiposity and physical activity levels between housing sectors was examined. If associations between outcomes and neighbourhood perceptions appeared linear, models examining housing sector differences were additionally adjusted for neighbourhood perceptions as a continuous variable.

Follow-up analyses

Multilevel linear regression models were fitted to examine the effect of moving to East Village on levels of physical activity and adiposity compared with controls who did not live in East Village (in all cases the distributions of residuals from the models were checked for normality). The primary outcome was specified a priori to be daily steps; secondary outcomes included time spent in MVPA (both total and in ≥ 10 minutes bouts per week), the daily sedentary time, BMI and fat mass percentage. 61 Average daily steps at follow-up was regressed on average daily steps at baseline, adjusting for East Village or control group as a fixed effect and baseline household as a random effect to allow for household clustering. Throughout, an alpha of less than 0.05 (p-value < 0.05) was used to determine the statistical significance of effects. Because of baseline differences in sociodemographic factors, further adjustment for participant characteristics, including sex, age group and ethnic group, were examined. Stratified models by housing tenure examined the effect in the different housing sectors (work status, occupation and child status were not adjusted for as these were strongly related to housing status). We also included an interaction term between East Village/control group and housing sector. Sensitivity analyses were carried out for daily steps, the primary outcome, by:

-

restricting the sample to those with at least 4 days of ≥ 540 minutes’ recording at baseline and at follow-up

-

repeating analyses for weekdays only and weekend days only (as this will modify exposure to the residential built environment)

-

comparing East Village participants with controls who remained at their baseline address at follow-up and controls who had moved elsewhere

-

examining the impact of missing accelerometry data at follow-up using imputation methods.

Results

At baseline

Overall participation rates and participation rates by housing sectors were outlined earlier (see Chapter 2). For the main outcomes of interest, complete data on adiposity were available for 1240 participants (97%); of these, a subset of 1107 participants (89%) met the inclusion criteria for analyses of objectively measured physical activity. Participant characteristics (age, sex, ethnicity) and levels of adiposity were similar among those who did and did not provide physical activity data; however, participants from black and Asian ethnic groups were less likely to provide physical activity data. Report Supplementary Material 2 shows characteristics of participants at baseline for the 1240 adults with measurements of adiposity at baseline, which are similar to those with physical activity data.

Adjusted mean levels of physical activity, and adiposity outcomes by housing sector and participant characteristics, are shown in Report Supplementary Material 3. Table 3 shows the association of housing sector and other participant characteristics with objectively measured physical activity (steps, time spent in MVPA, time spent in MVPA in ≥ 10-minute bouts) and BMI and percentage fat mass. Participants seeking social housing had markedly lower levels of steps, MVPA and MVPA in ≥ 10-minute bouts and markedly higher BMI and percentage fat mass than those seeking intermediate housing, although there were no differences between those seeking market-rent and those seeking intermediate accommodation.

| n | Daily stepsa | Daily minutes spent in MVPAa | Daily minutes spent in MVPA in ≥ 10-minute boutsa | BMI (kg/m2)b | Fat mass (%) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Differencec | 95% CI | p-value | Differencec | 95% CI | p-value | Differencec | 95% CI | p-value | Differencec | 95% CI | p-value | Differencec | 95% CI | p-value | ||

| Sex | ||||||||||||||||

| Male (reference) | 522 | – | – | – | – | – | ||||||||||

| Female | 718 | –570 | –946 to –194 | 0.003 | –9.3 | –12.2 to –6.4 | < 0.0001 | –4.1 | –6.1 to –2.0 | < 0.001 | –1.2 | –3.2 to 0.9 | 0.26 | 11.1 | 10.3 to 12.0 | < 0.0001 |

| Age group (years) | ||||||||||||||||

| 16–24 (reference) | 269 | – | – | – | – | – | ||||||||||

| 25–34 | 531 | 502 | 11 to 992 | 0.04 | 4.0 | 0.2 to 7.9 | 0.04 | 1.0 | –1.9 to 3.8 | 0.51 | 6.3 | 3.5 to 9.1 | < 0.0001 | 3.2 | 2.1 to 4.3 | < 0.0001 |

| 35–49 | 358 | 699 | 173 to 1224 | 0.01 | 3.9 | –0.2 to 8.0 | 0.07 | –1.1 | –4.0 to 1.8 | 0.46 | 13.4 | 10.2 to 16.6 | < 0.0001 | 6.4 | 5.2 to 7.6 | < 0.0001 |

| ≥ 50 | 82 | –9 | –832 to 813 | 0.98 | –6.0 | –12.4 to 0.5 | 0.07 | –2.0 | –6.8 to 2.7 | 0.40 | 17.6 | 12.6 to 22.9 | < 0.0001 | 9.2 | 7.3 to 11.0 | < 0.0001 |

| Ethnic group | ||||||||||||||||

| White (reference) | 595 | – | – | – | – | – | ||||||||||

| Black | 314 | –1116 | –1657 to –575 | < 0.0001 | –7.4 | –11.7 to –3.2 | < 0.001 | –6.6 | –9.8 to –3.4 | < 0.0001 | 6.2 | 3.3 to 9.3 | < 0.0001 | 3.6 | 2.4 to 4.8 | < 0.0001 |

| Asian | 210 | –1409 | –1972 to –845 | < 0.0001 | –11.5 | –15.9 to –7.0 | < 0.0001 | –8.1 | –11.4 to –4.8 | < 0.0001 | –0.3 | –3.1 to 2.7 | 0.85 | 0.02 | –1.2 to 1.3 | 0.97 |

| Other/mixed | 121 | –430 | –1100 to 239 | 0.21 | –4.6 | –9.8 to 0.7 | 0.09 | –4.0 | –7.9 to –0.04 | 0.05 | 1.3 | –2.3 to 5.0 | 0.48 | 1.0 | –0.5 to 2.5 | 0.18 |

| LLI | ||||||||||||||||

| No (reference) | 1087 | – | – | – | – | – | ||||||||||

| Yes | 153 | –1081 | –1666 to –496 | < 0.001 | –5.7 | –10.3 to –1.1 | 0.01 | –2.8 | –6.1 to 0.5 | 0.10 | 4.3 | 1.1 to 7.5 | 0.01 | 1.6 | 0.3 to 2.9 | 0.01 |

| Housing sector | ||||||||||||||||

| Social | 512 | –1125 | –1629 to –620 | < 0.0001 | –7.5 | –11.5 to –3.6 | < 0.001 | –6.5 | –9.5 to –3.5 | < 0.0001 | 5.0 | 2.2 to 7.8 | < 0.001 | 2.7 | 1.5 to 3.8 | < 0.0001 |

| Intermediate (reference) | 503 | – | – | – | – | – | ||||||||||

| Market-rent | 225 | –104 | –633 to 424 | 0.70 | 2.3 | –1.9 to 6.4 | 0.29 | 2.8 | –0.3 to 6.0 | 0.08 | –0.8 | –3.6 to 2.0 | 0.57 | –0.2 | –1.4 to 1.0 | 0.70 |

All physical activity measures were lower among females. Steps and MVPA were slightly higher in 25- to 34-year-olds and steps were also higher among 35- to 49-year-olds than among 16- to 24-year-olds; however, there were no age group differences for MVPA in ≥ 10-minute bouts. Participants of black and Asian ethnicities had lower levels of steps, MVPA and MVPA in ≥ 10-minute bouts than people of white ethnicity. Participants who reported having a LLI had lower levels of steps and MVPA, but not MVPA in ≥ 10-minute bouts. Percentage fat mass was higher in females than males, although there was no difference in BMI (see Table 3). BMI and percentage fat mass were higher among all older age groups than among 16- to 24-year-olds. Participants of black ethnicity had higher levels of BMI and percentage fat mass than people of white ethnicity; there were no differences in BMI and percentage fat mass between Asian or other/mixed ethnic groups and people of white ethnicity. Those with a LLI had higher levels of both BMI and percentage fat mass. Educational attainment level was not associated with any of the outcomes once housing sector had been adjusted for, and adjustment for educational attainment did not materially alter housing sector differences in physical activity or other outcomes (data not presented).

Sensitivity analyses for physical activity outcomes were carried out in 931 participants who wore an ActiGraph for ≥ 4 days with ≥ 540 minutes of recording per day at baseline (see Report Supplementary Material 4). There were no differences between market-rent and intermediate groups (consistent with the main analysis presented in Table 3). Differences between social and intermediate groups were broadly similar with the results presented in Table 3 for the main analysis.

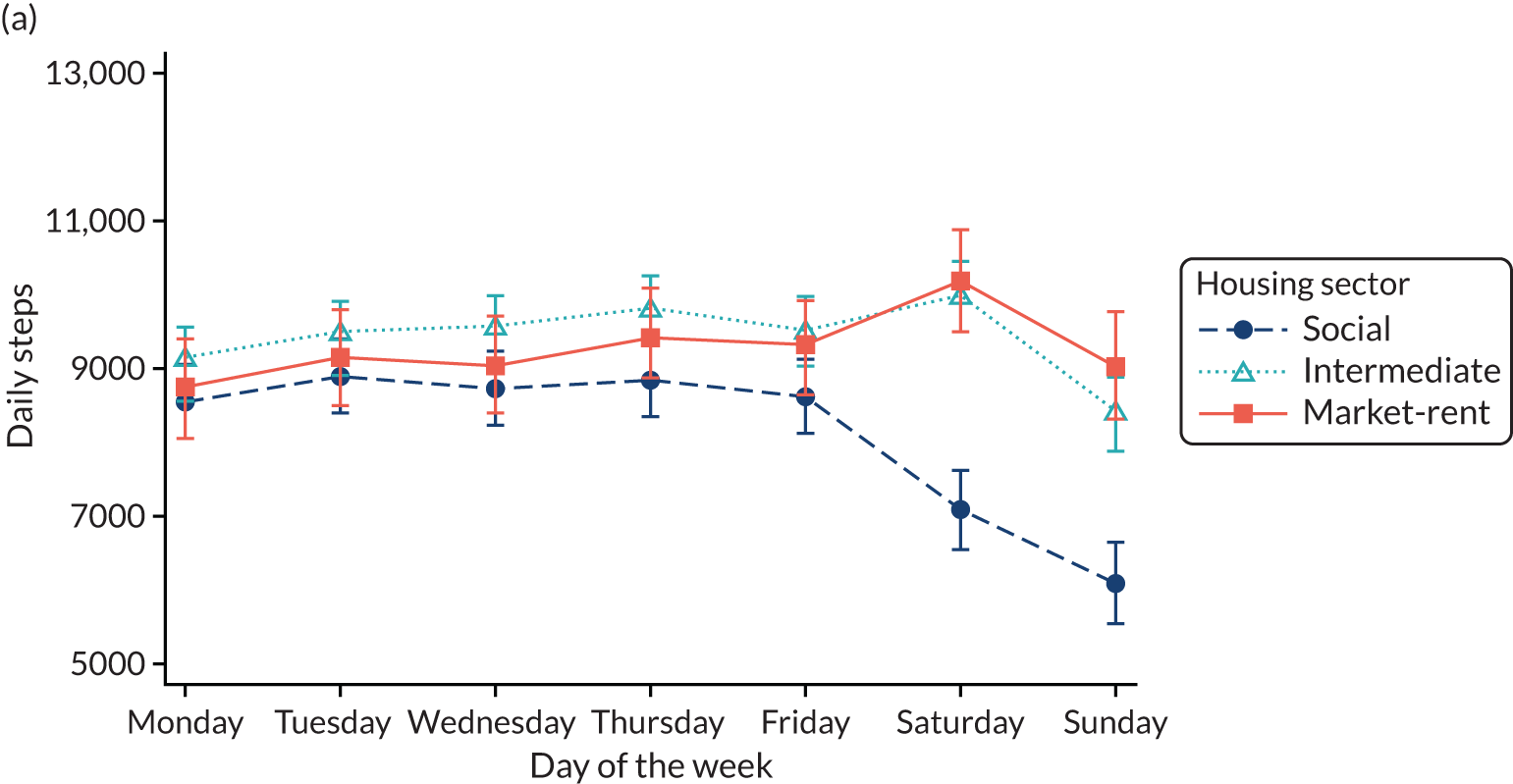

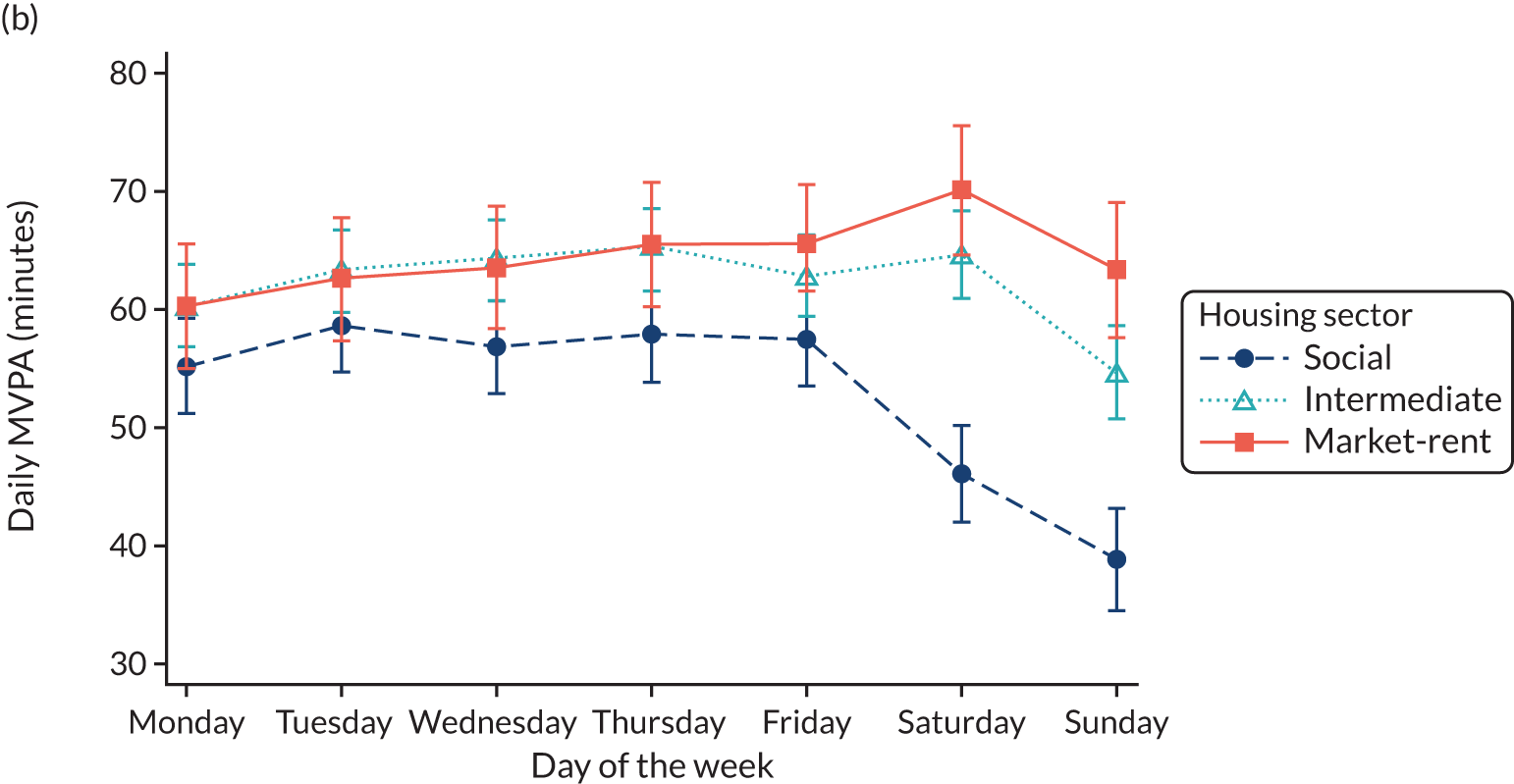

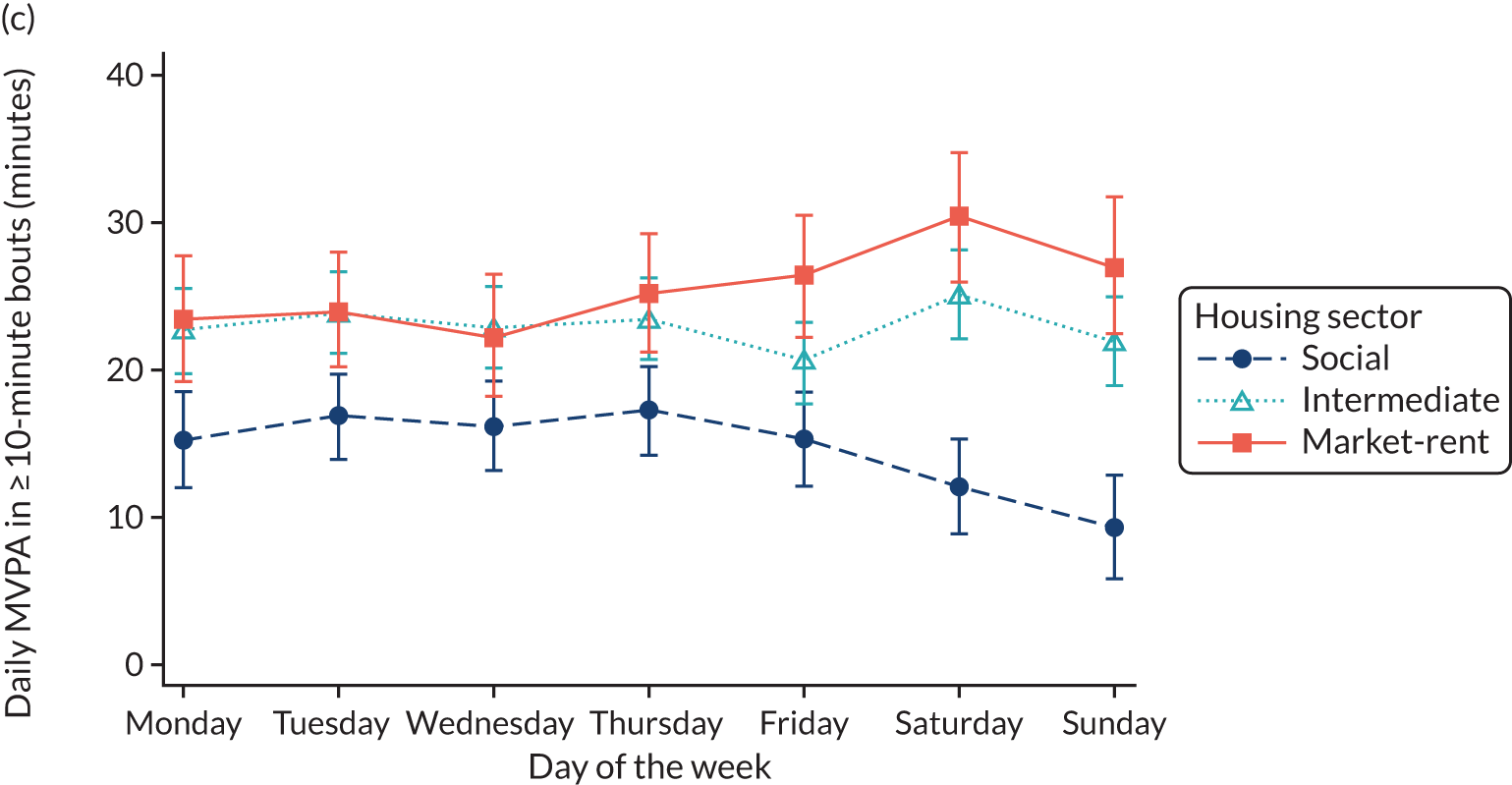

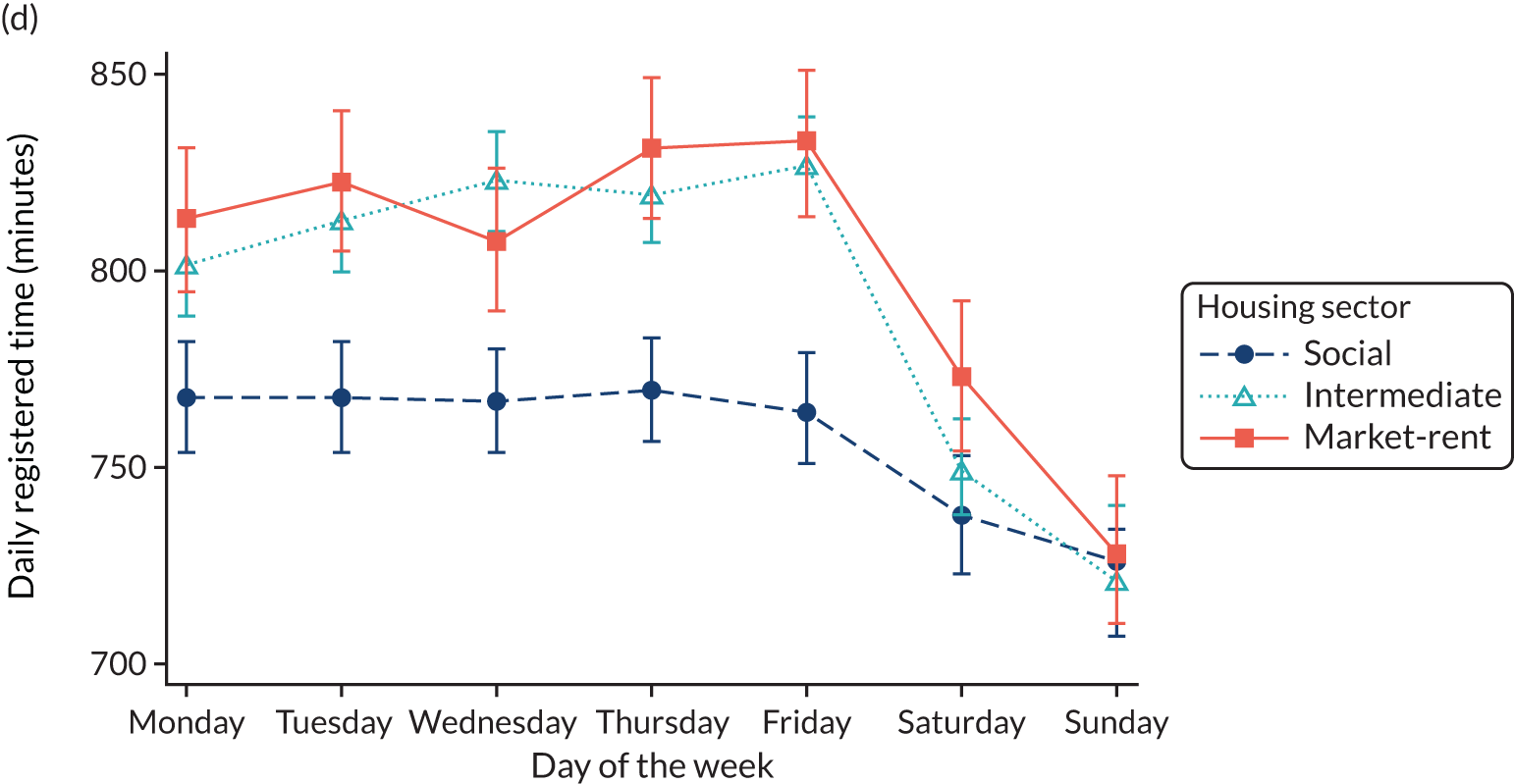

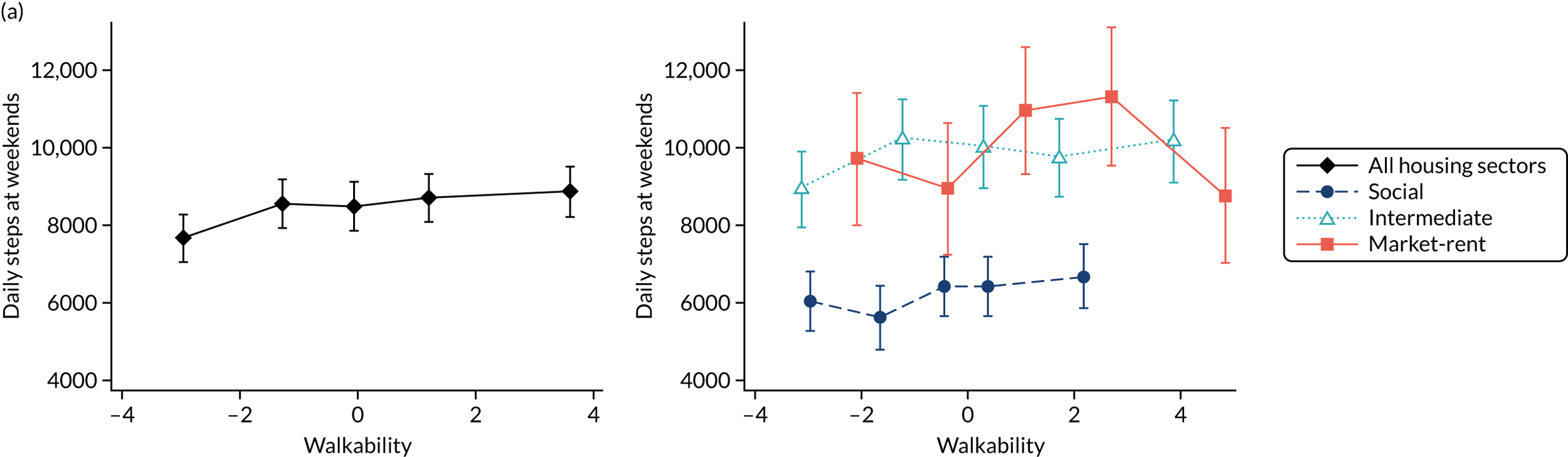

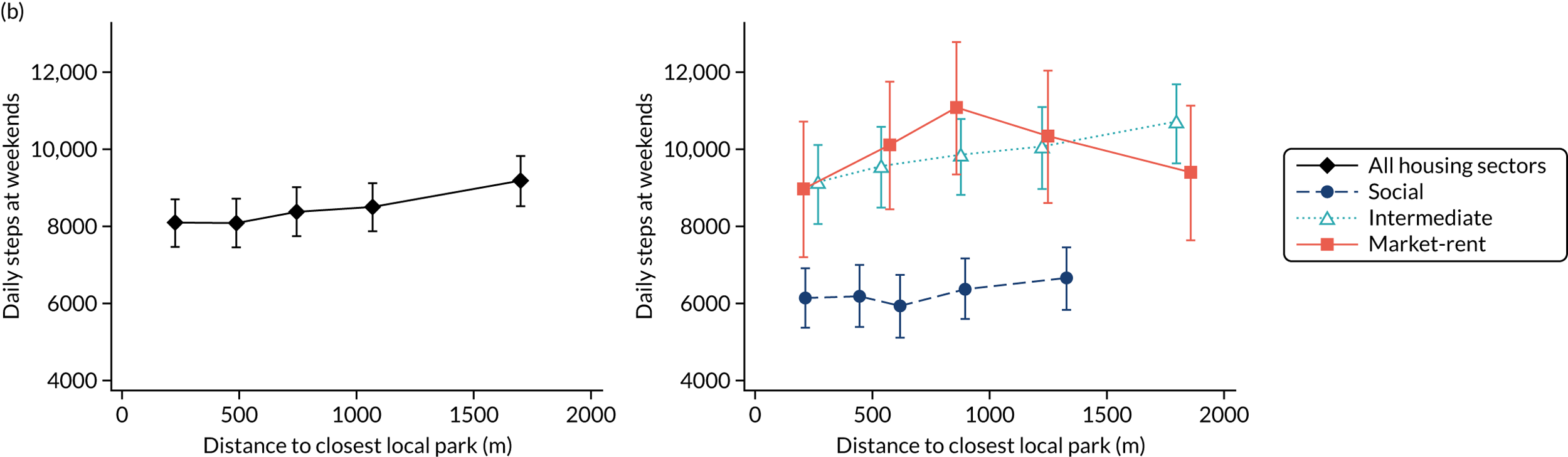

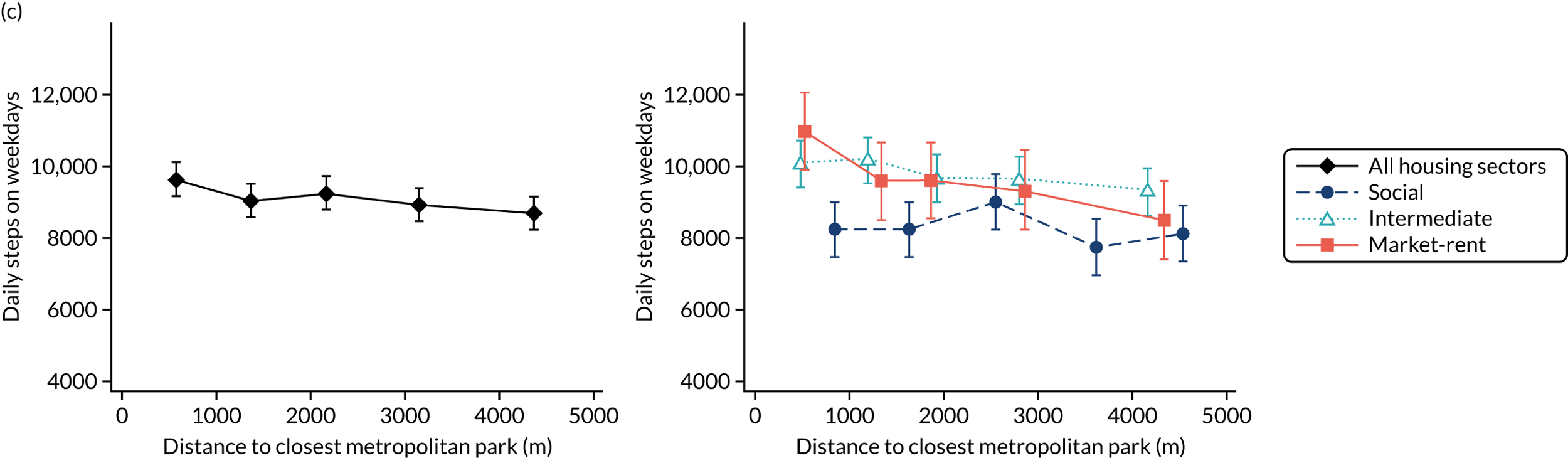

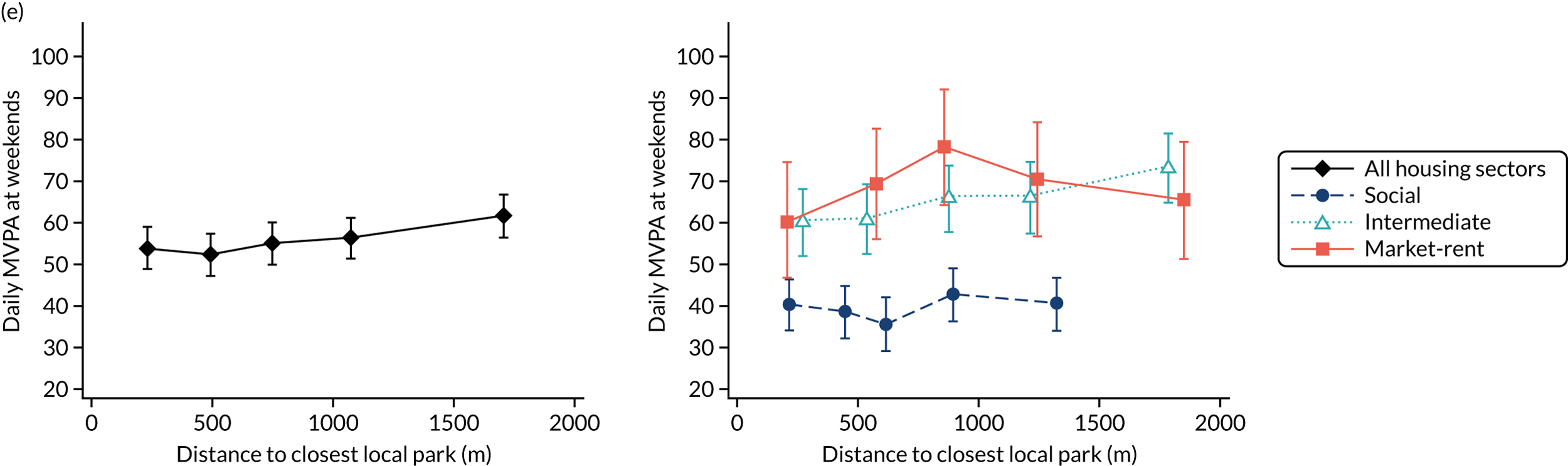

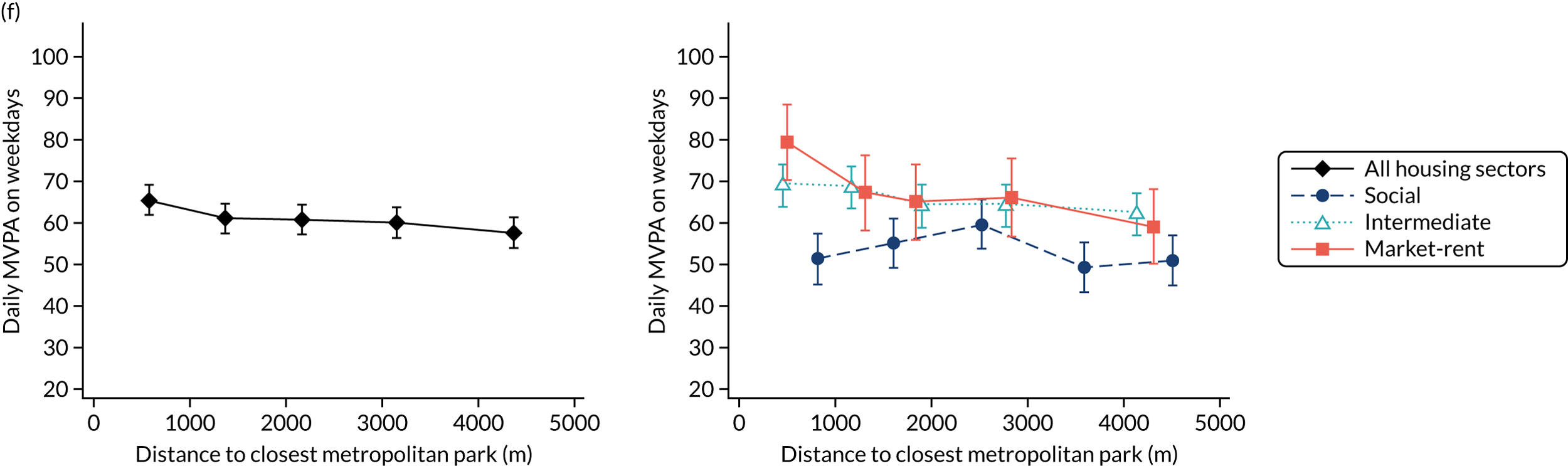

Baseline differences in physical activity variables between housing sectors were examined by day of the week to explore whether or not differences between sectors were consistent across the week (Figure 3). Levels of physical activity [steps (Figure 3a), MVPA (Figure 3b) and MVPA in ≥ 10-minute bouts (Figure 3c)] were generally consistent across weekdays (Monday to Friday) among all groups. In the intermediate group, steps were higher on Saturdays and lower on Sundays; MVPA and MVPA in ≥ 10-minute bouts were lower on Sundays, but there was no difference on Saturdays compared with weekday activity. In the market-rent sector, steps, MVPA and MVPA in ≥ 10-minute bouts were higher on Saturdays and similar to weekdays on Sundays. In the social group, steps, MVPA and MVPA in ≥ 10-minute bouts were on average lower on Saturdays and lower still on Sundays. Registered time of recorded physical activity (Figure 3d) was lowest on average in the social group during weekdays, decreasing on Saturdays and Sundays. The intermediate and market-rent groups had higher levels of registered time during weekdays than the social group, which decreased on average on Saturdays and Sundays (despite recording more steps and minutes in MVPA, suggesting a higher intensity of activity). Mean levels of steps, MVPA, and MVPA in ≥ 10-minute bouts on weekdays, and differences on Saturday and Sunday compared with weekdays, are shown by housing sector in Report Supplementary Material 5. The marked differences in activity between weekdays and weekend days in the social group were not explained by differences in registered time.

FIGURE 3.

Daily physical activity by day of the week and housing sector: N = 6206 days from 1107 participants. Means and 95% CIs are adjusted for sex, age group, ethnic group, LLI, month of recording, day order of recording, day of week, housing sector, an interaction between housing sector and day of week and random effects to allow for multiple days of measurement and clustering of participants within households. Reproduced from Nightingale et al. 70 © Author(s) (or their employer(s)) 2018. Re-use permitted under CC BY. Published by BMJ. This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Associations between perceived neighbourhood quality and crime scales, and physical activity and adiposity outcomes are shown in Table 4, adjusted for the participant characteristics (see Table 3). Participants with the most positive perceptions of neighbourhood quality (highest quintile) had higher steps, recorded longer durations of MVPA and had a lower BMI than those who had the most negative perceptions of neighbourhood quality (lowest quintile). There were no significant associations between perceptions of neighbourhood crime and physical activity or adiposity.

| Outcome | Perceptions of neighbourhood | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality | Crime-free | |||||

| Differencea | 95% CI | p-value | Differencea | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Physical activity (N = 1107) | ||||||

| Daily steps | 677 | 108 to 1247 | 0.02 | –63 | –713 to 587 | 0.85 |

| Daily MVPA (minutes) | 4.5 | 0.02 to 9.0 | 0.05 | 1.1 | –4.0 to 6.2 | 0.68 |

| Daily MVPA in ≥ 10-minute bouts (minutes) | 2.7 | –0.6 to 6.0 | 0.11 | 2.4 | –1.4 to 6.1 | 0.22 |

| Adiposity (N = 1240) | ||||||

| Body mass index (kg/m2)b | –3.6 | –6.5 to –0.6 | 0.02 | –2.1 | –5.4 to 1.3 | 0.21 |

| Fat mass (%) | –1.2 | –2.5 to 0.06 | 0.06 | –0.8 | –2.2 to 0.7 | 0.30 |

The effect of adjustment for perceived neighbourhood quality on the differences in physical activity and adiposity between housing sector groups is presented in Table 5. All associations between perceived neighbourhood quality and crime-free neighbourhood and outcome variables were approximately linear and were therefore fitted as continuous variables in the model. In addition, associations between perceived neighbourhood quality and crime-free neighbourhood and outcome variables were similar across the three housing sectors (all p > 0.05). Adjustment for perceptions of neighbourhood quality reduced the differences in steps (by 10%), MVPA (by 10%) and MVPA in ≥ 10-minute bouts (by 7%), BMI (by 10%) and percentage fat mass (by 6%) between the social and intermediate groups. Differences between market-rent and intermediate groups in adiposity and physical activity variables were not statistically significant before or after adjustment. Larger proportions of the social–intermediate group differences in steps, MVPA and MVPA in ≥ 10-minute bouts on weekends were explained by adjustment for perceptions of neighbourhood quality (10%, 16% and 16%, respectively) than that for weekdays, which were reduced by 10%, 8% and 3% respectively (data not shown).

| Outcome | Housing sector | Model 1a | Model 2b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Differencec | 95% CI | p-value | Differencec | 95% CI | p-value | ||

| Physical activity (N = 1107) | |||||||

| Daily steps | Social | –1125 | –1629 to –620 | < 0.0001 | –1016 | –1531 to –501 | < 0.001 |

| Intermediate | Reference group | ||||||

| Market-rent | –104 | –633 to 424 | 0.70 | –96 | –624 to 431 | 0.72 | |

| Daily MVPA (minutes) | Social | –7.5 | –11.5 to –3.6 | < 0.001 | –6.8 | –10.8 to –2.7 | 0.001 |

| Intermediate | Reference group | ||||||

| Market-rent | 2.3 | –1.9 to 6.4 | 0.29 | 2.3 | –1.8 to 6.5 | 0.27 | |

| Daily MVPA in ≥ 10-minute bouts (minutes) | Social | –6.5 | –9.5 to –3.5 | < 0.0001 | –6.0 | –9.1 to –3.0 | < 0.001 |

| Intermediate | Reference group | ||||||

| Market-rent | 2.8 | –0.3 to 6.0 | 0.08 | 2.8 | –0.3 to 6.0 | 0.08 | |

| Adiposity (N = 1240) | |||||||

| Body mass index (kg/m2)d | Social | 5.0 | 2.2 to 7.8 | < 0.001 | 4.5 | 1.7 to 7.3 | 0.002 |

| Intermediate | Reference group | ||||||

| Market-rent | –0.8 | –3.6 to 2.0 | 0.57 | –0.9 | –3.6 to 2.0 | 0.55 | |

| Fat mass (%) | Social | 2.7 | 1.5 to 3.8 | < 0.0001 | 2.5 | 1.4 to 3.6 | < 0.0001 |

| Intermediate | Reference group | ||||||

| Market-rent | –0.2 | –1.4 to 1.0 | 0.70 | –0.2 | –1.4 to 0.9 | 0.68 | |

At follow-up

In total, 877 adults (69%) from 710 households were examined after 2 years; 441 (50%) had moved and were living in East Village at follow-up. Data were available at baseline and follow-up for 762 participants for physical activity outcomes and 822 participants for adiposity variables. There were no differences in age, sex or ethnic group between those followed up and not followed up (see Report Supplementary Material 6), although those followed up had slightly higher socioeconomic status and recorded more sedentary time at baseline than those not followed up.

Baseline characteristics for the 877 adults who were seen at follow-up are shown in Table 6, by housing sector and overall. In the social housing sector, age, sex, socioeconomic status and children in the household were similar for those living in East Village and for controls, although the East Village group had a higher proportion of participants of black African/Caribbean ethnic origin and a lower proportion of participants of Asian ethnic origin than the control group. In the intermediate sector, the East Village group were younger, less likely to be female, and more likely to be of white ethnicity, be economically active and have no children in the household than controls. In the market-rent sector, age, sex, ethnicity, socioeconomic status and children in the household were similar in the East Village and control groups. For housing sectors combined, the proportion of females in the two groups was similar, but participants in the East Village group were younger, more likely to be of black African–Caribbean ethnicity, less likely to be of Asian ethnicity and less likely to be in higher managerial/professional occupations than the control group. Overall, baseline daily steps and daily levels of MVPA were greater in the control group than in the East Village group, although differences by housing sector were less apparent. Although there was no overall difference in baseline adiposity levels, controls in the intermediate group had higher levels of BMI and fat mass percentage than those living in intermediate East Village accommodation. Those who had moved to East Village reported a sizable increase in scores for the perceptions of crime-free neighbourhood and higher quality neighbourhood at follow-up (Table 7 and Report Supplementary Material 7). Compared with baseline data, participants living in East Village at follow-up lived closer to their nearest park, had better access to public transport and lived in a more walkable area (see Table 7 and Report Supplementary Material 7).

| Characteristic | All housing sectors (N = 877) | Housing sector | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social (N = 344) | Intermediate (N = 377) | Market-rent (N = 156) | ||||||||||