Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 15/24/17. The contractual start date was in July 2016. The final report began editorial review in January 2020 and was accepted for publication in October 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2021 Osborn et al. This work was produced by Osborn et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 Osborn et al.

Chapter 1 Ethics

Ethics approvals were gained for all parts of the study from London Bloomsbury Research Ethics Committee (reference 16/LO/2160). In addition, enhanced ethics approvals were gained for work package (WP) 3 from the Confidentiality Advisory Group (reference 17/CAG/0101). Confidentiality Advisory Group approvals were required to use routine clinical data for which service users had not individually given consent to be used in research.

Chapter 2 Introduction

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Lamb et al. 1 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

There are well-established challenges facing acute mental health care for people experiencing crises. These include poor experience of services, lack of provision of recommended interventions, delays in accessing care, poor continuity of care, over-reliance on restriction orders, use of police for conveyance, overcrowding in emergency departments and continuing issues with reduced bed capacity. 2,3 A range of reports have highlighted the need for better mental health crisis care in the UK, including the recent Care Quality Commission report about mental health services,4 the Chief Medical Officer’s report in 2013,5 the Crisis Care Concordat6 and the final report by the Commission on Acute Adult Psychiatric Care. 7

Crisis care is typically provided by inpatient wards in hospitals and by crisis resolution teams (CRTs), which are multidisciplinary teams who visit service users at home to provide medication and interventions to prevent admission to inpatient wards. These existing services can be augmented by acute day units (ADUs), which have the potential to address some of the challenges mentioned above. These units offer intensive, short-term community responses to mental health crises, and aim to reduce costly and unpopular admissions, either by avoiding them or by facilitating early discharge. ADUs may be particularly helpful for people who are socially isolated or have poor social support, lack activities or would benefit from peer support or group interventions. Previous research reported that around one in five NHS mental health CRTs in England had access to ADUs within their catchment area. 8

Non-residential day services, previously known as ‘day hospitals’, have been a component of adult mental health services for decades, particularly across Europe. 9 The interventions that ‘day hospitals’ offered were varied, but typically involved longer periods of care than those offered by more recent versions of these. The model for ADUs in the NHS has moved towards providing a shorter period of care, avoiding or shortening inpatient admission by supporting people in the acute phase of their illness. In addition to NHS services, the UK has many non-residential crisis services provided by voluntary sector organisations, which typically offer social interventions and support rather than medical or psychological treatment, for example drop-in ‘crisis cafes’, although research on such services is lacking. 10

Cochrane systematic reviews11,12 have compared acute day hospitals with both outpatient and inpatient psychiatric care. The limited available evidence is not only rather dated, but also heterogeneous in terms of study participants, design and outcomes, making conclusions difficult. The most recent meta-analysis12 involved 10 randomised controlled trials conducted in the USA and Europe. It concluded that mental health day units were as effective as inpatient care in terms of re-admission rates after discharge, employment, quality of life and treatment satisfaction, but that more research was needed to establish the cost-effectiveness of such units.

The most recent British randomised controlled trial,13 involving one London ADU and three inpatient wards, was also promising, reporting that symptom improvement and satisfaction were greater at discharge in the ADU group. This trial found that costs for ADU patients overall were higher than for inpatients, but this was largely a result of mean ADU admissions being nearly twice as long as inpatient admissions (55.7 ADU days vs. 30.5 inpatient days), with the cost per day of ADU treatment being only 70% that of inpatient care.

There is lack of more recent research about ADUs. 12 In the UK, this is likely to be because, although CRTs became mandatory with the 2000 NHS Plan,14 other acute community services such as crisis houses and ADUs were not established nationwide. A recent survey of CRTs8 found that just 22% (40/185) had access to an ADU, and we know from this research that implementation of acute services in practice is often highly variable and suboptimal.

The Crisis Care Concordat6 includes crisis care and acute day care in its suggested domains, and ADUs address many of the ambitions in the NHS Five Year Forward View,14 including making improvements to acute care, personalised care, empowerment and efficiency. ADUs have the potential to be an important part of a well-developed crisis care system, offering user choice and greater possibilities for tailoring response to needs, but we currently lack clear evidence about how best to integrate them into contemporary systems.

Chapter 3 Patient and public involvement

Our service user involvement was planned from the outset both to provide advisory input into the project from a lived experience perspective and to become more involved in the qualitative research component that was peer led, using a range of expertise from experience. This was achieved in the following ways:

-

We worked with two service users to review the original proposal (prior to submission), and one reviewer joined the patient and public involvement (PPI) team as an advisor. They were involved throughout the study.

-

We recruited two additional PPI advisors, both of whom have experience of using acute day units as mental health service users. This provided a small PPI advisory team of three people and a PPI co-applicant lead (VP). We had planned for this group to comprise five people but did not receive that many applications to join the study advisory group, and over time it worked well as a group of three.

-

We recruited a sessional peer researcher to work alongside a University College London (UCL) peer researcher employed on the project full-time for part of the study. The sessional peer researcher ensured that we could deliver as a team the qualitative component with interviews, observation work and analysis shared under the direction of an experienced qualitative specialist (NM).

Advice work

We made some changes to our ways of working in the project early on:

-

First, we decided that, to understand the acute day units that were the focus of the study, to the best of our ability, we wanted to visit them. Thus, we held some of our PPI meetings at acute day units selected for the case study work. In total, we visited three out of the four units.

-

Second, to stay up to date with progress in the study, we were invited to all project team meetings. PPI members attended in person or by telephone. These were held with co-applicants and project staff regularly throughout the study. This was made possible by the PPI group being small.

After each meeting we wrote up reflection notes, including perspectives on how our expertise by experience had been used in a session and changes that the team could make to be more inclusive. Reflection notes were sent to the PPI lead. Extracts from some of the reflection notes are provided in the following sections. The first focuses on the value of involving people ‘from the start’.

Reflection 1: my involvement in the AD-CARE research project

After I was appointed, I was immediately included in the very first meeting at the university to discuss the study. This was both exciting for me and formative for the study because I was able to add my penny’s worth to the perception of ADUs by service users. It was clear to me that the service user voice was very much part of the study. From the outset I felt included at every stage of the process and David Osborn, the team lead, ensured service users understood the jargon and the issues. We were also asked after every point made by other team members what our views were on the matter. Clearly the fact that ADUs were part of the treatment on offer for service users was a key reason for the study.

As part of our active involvement we wrote reflections after each session. After the first meeting I reflected that community day centres and OT-run [occupational therapy-run] day care at the hospitals were part of my recovery, but had been closed. There had been an overall reduction in recovery possibilities and clinical support for the most vulnerable. Service users generally did not have a voice in changes or initiatives. Thus, studying ADUs in the midst of these closures and austerity took on an additional and more important role of preserving records whilst the service was still in place.

It was suggested by our McPin PPI lead, Vanessa Pinfold, that we all go to visit an ADU. The team met up by arrangement at [XXXX] in [XXXX] and we spent several hours discussing with staff what was on offer. This vibrant centre gave us a positive feel for ADUs. Ironically, before the study was completed this ADU was closed. However, the insights we gained there showed what an important role ADUs could play in mental health treatment and we could use it as a benchmark to the others we visited and studied.

Key tasks

The key tasks of the PPI group in terms of advisory input were as follows:

-

In project management meetings, scrutinising progress, being curious about emerging findings and helping with problem-solving.

-

Lived experience advisory group meetings – small sessions with only the lived experience advisory group present alongside programme manager. One session included training in coding qualitative data. In lived experience advisory group meetings, we helped develop interview guides, kept up to date with study progress and planned dissemination activities.

-

Visiting acute day units, observing the environment and the activities provided and reflecting on these personally. We recommended that photographs were taken of the units to help get a sense of the space and environment.

One of the challenges for any research study is keeping the PPI group informed and engaged over several years. Some members are not able to attend all arranged meetings, and when the meetings are infrequent this can lead members to feel disconnected and lost.

Reflection 2: the challenges of being involved in the AD-CARE research project from a distance

I am a former mental health service user, and in the past I have used an acute day care hospital in one of the trusts that AD-CARE has been doing its research. I have been to most of the meetings; two I attended via telephone. One was a meeting where the team were visiting the acute day care hospital in the trust that covers the area that I live in. However, I do not have access to my own transport and I had already committed myself to other work each morning. It would have been quite stressful and pressured to get there, so the decision was taken that I could ring in after the group had their tour. I was grateful that there was the option to be part of this meeting via teleconference. However, I would have to say that the experience was quite stressful and difficult. It left me quite frustrated.

Towards the end of the project, logistics meant that a face-to-face PPI meeting took place in London a week after I had had a major operation. I had at first been upset at the timing of this as I live over 100 miles away from London. However, I was told that the team could ring me and I could contribute that way, which was a great relief. The documents were e-mailed to me the day before and I was able to prepare for the meeting as I usually would have. This experience was so much better than the previous one. I was able to hear what was being said and a big effort was being made to involve me.

Over the last few years the lived experience advisory panel have been invited to the research team meetings for an hour. Myself and another member have telephoned into these. It has been good to be part of them but there have been issues with hearing what was going on, not really knowing some of the people there, not being able to hear very well, making it contributing hard and frustrating; quite a difficult experience. On one occasion I rang off quite upset. I was later offered support by the PPI lead but these calls are examples of where technology has been a mixed blessing.

Inclusivity

Overall, we sought to employ strategies that were inclusive but also tailored to individual needs. We recognised that the involvement of all PPI members in project update meetings was useful but, as these meetings were short and fast-paced and included often quite technical language, support was required for some members to feel able to contribute. An important innovation in this study was PPI meetings at ADU sites, which helped all of the team more fully contextualise the ‘topic’ of study. We also recommended the photographs were taken of the sites, and this provided an important record to share with other team members.

Reflection 3: visiting units

It was interesting to visit an ADU. In all, I visited three units and it brought the study alive: meeting staff, seeing the activities on offer, meeting a few service users, looking at the physical environment of the unit including artwork and positive recovery messages.

The reason I got involved in the ADU study is because I wanted to see how ADUs provided alternative crisis support for people. I felt strongly uncomfortable with some units being attached to acute inpatient hospital. This can create a feeling of being associated with being sectioned, as some patients were probably compulsory sectioned on the ward. I found that the locations did vary – stand-alone units, co-location on hospital site, some in cities with good transport links, others where clients have to rely on hospital transport to attend. Inside, these units also varied. One had a joint staff service user communal area; in another the staff office space was separate. There were units with clear disability access, including wide corridors, and others were in old repurposed buildings, sharing rooms with other services. I found a strong sense of the creative in the units, maybe too much emphasis on artwork for my liking in one [see Figure 1 ]. I found it was really important part of our work, visiting the units. I had strong reactions and it helped me reflect on my current views. I had last seen one in 2008 – I needed to update my knowledge, and I feel I have.

FIGURE 1.

Photographs of artwork displayed in one of the participating ADUs.

Peer research sessional input

The PPI model in this project included the appointment of a sessional researcher. Their role was to support the UCL-based peer researcher in completing the qualitative component of the study that explored service user, carer and staff views of ADUs. This model had advantages, including peer input until the end of the qualitative study (as the main post ended early), both male and female perspectives within the peer research team, team support and different lived experiences to draw on. However, there were also challenges.

Overall, the peer-led research in the study provided a significant research component for the PPI group to shape. Much of the other WPs was limited by data availability in existing data sets. It also led to the development of significantly new skills.

Reflection 4: challenge of working within academic environment

Whilst overall my experience has been a positive one, an area of unforeseen difficulty has been where I belong within the teams. I am employed by the McPin Foundation as a sessional peer researcher but have worked predominantly within the UCL research team. My experience has shifted in this time; at the start of the project I worked closely with the full-time peer researcher and whilst we were doing interviews it was easy to maintain good contact. When we shifted to the analysis this was not so easy as I worked remotely. Then the full-time peer researcher left to do other work and I also joined other projects – maintaining contact and ‘in’ the research became more difficult. I also felt a bit cut adrift because I wasn’t quite sure which team I should identify with. The impact of this was that I did not have a sense of belonging to any specific team. This may have been mitigated by having more clarity around my role in the beginning. This was a new way of working and was an unintended consequence; with reflection, an overview of the team structure, demarcation of roles and more regular meetings, perhaps by Zoom or Skype if this was not practical, would be helpful adjustments to make.

Reflection 5: peer researcher significant moments

Right from the moment of interview I have felt that my skills as a researcher as well as my lived experience have been equally valued. I was very excited to be able to put both sets of skills to good use and I have not been disappointed. At no point have I felt like the proverbial ‘token presence’. When I compare my experience of using my lived experience of mental health difficulties within care settings with my experience within a research setting – I would suggest that research teams are way ahead of the game. I wonder if this is because the ethos of social science is to value the individual’s experience as important data for research and the stringent ethical considerations that go alongside this. Perhaps an area for future research? I have felt privileged to be interviewing my peers and the opportunity (and responsibility) of attempting to represent their voice accurately in this research. There is something unique about the relationship a peer researcher can offer an interviewee, which can enhance the data that is gathered; the knowing nod of a shared understanding really does go a long way. As I have visited ADUs, and hearing the vast array of positive experiences from my peers, I am struck once again by (1) the need for an approach to mental health care that has ‘relationships’ at its centre; and (2) the need for those with lived experience of mental health illness to be the ones asking the questions. This has been a valuable experience and one where I have been able to develop my skills as a researcher, and to have such an investment in the whole process has been a great opportunity.

Recommendations from the patient and public involvement team

This study was challenging in terms of PPI in several respects. First, there were several periods when the focus was data collection or analysis of the Mental Health Minimum Data Set (MHMDS) and there was less work for the PPI group to do. Keeping people involved and up to date on progress was important, and we recommend the inclusion of members in project team meetings. Although large telephone conference calls can be difficult, with support this is a workable solution. Second, the PPI team experience of ADUs was not recent, and to address this we decided to update our knowledge through site visits. We recommend this approach to other teams, as taking research team meetings into places that are the subject of the study is very valuable. This would also benefit wider team members, including statisticians and economists, who might not be familiar with the environment that forms the focus of a study. Third, it can be tricky to involve sessional peer researchers working ad hoc, but this can add important expertise and capacity to the study team. In our case, it ensured that a small team of peer researchers was formed, and we had input throughout the study, including write-up. The danger is that they can become excluded from certain tasks, such as analysis and write-up, because of lack of time on the study or because of projects taking longer than original contracted periods. We recommend studies plan these roles carefully, including support arrangements, and ensure sufficient funding for involvement so that meaningful roles can be shaped.

Chapter 4 Work package 1: national mapping and survey of acute day units for mental health care in England

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Lamb et al. 1 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Methods: mapping and survey

Design

This was a mapping exercise to identify existing ADUs for mental health in England, followed by a questionnaire survey of ADU managers.

Objectives

-

To produce a mapping of existing ADUs for mental health in England.

-

To collect data via a cross-sectional questionnaire on the characteristics and service functioning of ADUs.

-

To ascertain whether or not there are distinct ADU models, and, if so, to characterise them.

Setting and participants

All NHS mental health trusts in England were contacted to ascertain whether or not they provided an ADU service. In addition, voluntary sector non-residential crisis day services were sought. NHS trusts that provided at least one ADU, and any relevant voluntary sector services, were included in the study.

ADUs were defined for this survey as non-residential services offering daytime treatment and care to adults experiencing a mental health crisis who would otherwise be considered for acute psychiatric hospital admission, or other alternatives to admission (including crisis resolution services). Services were excluded that:

-

provide rehabilitation, rather than acute care

-

work only with groups of service users who would not be considered for acute psychiatric hospital admission

-

work primarily with populations other than people with mental illness, such as older adults or people with dementia, learning difficulties or primary drug or alcohol dependence disorders

-

do not accept referrals for service users currently living at home (i.e. exclusively provide ‘step-down’ care from hospital)

-

routinely work with service users for longer than 3 months (i.e. longer-term support rather than acute care)

-

do not accept referrals from the local CRTs.

Non-NHS services that met the above criteria were included in the survey. Day services providing dedicated acute care meeting the above criteria within a broader service were also included.

Measures

We used a survey developed for the AD-CARE study (the full survey is available in Report Supplementary Material 1). The survey was provided online via the secure UCL Opinio website, and could be completed over the telephone with a researcher. The survey included questions covering the following areas: location and access, throughput and service user characteristics, integration with other services, service organisation and staffing, interventions provided, service user experience, service development, and outcomes data.

Procedure

All 58 NHS mental health trusts in England were contacted (August 2016) to enable ADUs to be located. The following methods of contact were used:

-

All England NHS mental health trust websites were screened.

-

Local communications teams, patient advice and liaison service teams, research and development teams, trust headquarters, local acute care leads or other appropriate clinical staff were contacted by telephone and e-mail.

-

Relevant professional organisations and networks (e.g. the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ Acute Care Network and Mind’s Acute Care Campaign) were contacted on Twitter (Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA; www.twitter.com) and by e-mail and telephone.

-

The CRT managers of all teams that had been identified as having an ADU in the 2012 CRT Optimisation and Relapse Prevention (CORE) study survey8 were contacted.

-

Online searches were conducted for any voluntary sector services that met the inclusion criteria.

Where ADUs were identified, study researchers contacted the service managers by telephone to explain the survey, answer any questions and obtain e-mail/postal addresses to enable them to send out information sheets.

Managers (or alternative ADU clinicians with appropriate knowledge and experience) were asked to complete a questionnaire either online or over the telephone with a researcher. Participants were assigned a unique, anonymised study ID. All data were entered into the questionnaire in Opinio and then extracted into Microsoft Excel® version 16 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and SPSS version 24 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) for data analysis. Data collection was carried out from September to November 2016.

Those who did not respond were followed up by study researchers by telephone and e-mail. Any service that declined to complete the survey was not contacted further.

A brief follow-up survey was conducted 1 year after initial data collection (October 2017) to ascertain whether any ADUs had opened or closed. Services identified in the original mapping exercise were contacted by telephone and e-mail to check that they were still operating and to identify any changes to services.

Analysis

As outlined above, the survey had two main aims: (1) to establish a typology of ADU models and (2) to describe current practice in ADUs.

A cluster analysis was carried out to address aim 1. A cluster analysis is a way of grouping units so that those units more similar to each other appear in the same cluster. The process aims to minimise variability within clusters and maximise variability between clusters. There were four stages in this process:

-

Potential grouping variables were identified. These were collated from the questions in the survey, with some grouping variables obtained by the amalgamation of multiple survey questions covering the same topic.

-

The expert working group ranked the list of potential grouping variables, ordering them by most to least important in distinguishing different types of ADUs.

-

The five highest-ranked grouping variables were included in a cluster analysis (where a grouping variable was considered to have poor-quality data available from the survey, it was discarded, and the next highest-ranking variable was used instead). Five is considered an appropriate number of grouping variables to include in this type of analysis.

-

The cluster analysis was refined, with different models run to establish the most appropriate number and composition of groups.

The resulting variables were used in a cluster analysis using SPSS software.

To address aim 2, descriptive data were collated for each survey question, including range, mean and median scores.

Results: mapping and survey

Cluster analysis

Eight members of a multidisciplinary expert working group ranked 14 variables in the survey identified as relevant to ADU type (Table 1). Variables were ranked by participants, using 1 to indicate the most important and 14 to indicate the least important, meaning that those variables with the lowest total scores were considered (by consensus) to be the most important in distinguishing services from each other.

| Variable | ADU service characteristic | Expert working group raters (anonymised) | Total | SD | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||||

| 1 | Interventions provided | 2 | 3 | 8 | 2 | 7 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 24 | 2.88 |

| 2 | Service provider (statutory/voluntary/joint) | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 11 | 6 | 29 | 3.58 |

| 3 | Client group served | 1 | 4 | 9 | 4 | 12 | 14 | 2 | 2 | 34 | 4.10 |

| 4 | Length of ‘stay’ | 7 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 11 | 6 | 5 | 34 | 2.27 |

| 5 | Staffing (types of staff) | 4 | 9 | 7 | 6 | 3 | 9 | 5 | 4 | 38 | 2.07 |

| 6 | Referral sources | 5 | 13 | 1 | 13 | 6 | 13 | 7 | 3 | 48 | 4.63 |

| 7 | Opening hours | 8 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 14 | 4 | 4 | 9 | 51 | 3.45 |

| 8 | Service user/carer involvement | 14 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 1 | 10 | 7 | 60 | 3.05 |

| 9 | Gatekeeping | 11 | 12 | 12 | 7 | 8 | 12 | 3 | 8 | 61 | 3.25 |

| 10 | Co-location of services | 13 | 2 | 13 | 10 | 1 | 2 | 12 | 14 | 65 | 5.47 |

| 11 | Size/usage of service | 6 | 7 | 11 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 13 | 10 | 65 | 2.36 |

| 12 | Staffing levels (staff FTE : daily attendance) | 10 | 10 | 4 | 12 | 11 | 7 | 9 | 12 | 68 | 2.75 |

| 13 | Joint management of services | 12 | 11 | 14 | 11 | 4 | 3 | 14 | 13 | 79 | 3.45 |

| 14 | Discharge destinations | 9 | 14 | 10 | 14 | 13 | 6 | 8 | 11 | 79 | 2.43 |

Two-step cluster analysis was used to enable the inclusion of categorical and continuous variables, and for the automatic determination of the optimal number of clusters.

Cluster model 1 for acute day unit types

The first model used variables 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 (see Table 1), and it identified two clusters. Cluster 1 included services that offered a larger number of interventions, a longer average length of ‘stay’ and a more multidisciplinary staff team; the services were more likely to be provided by the NHS and to have restrictions on the types of clients they took on. Services in cluster 2 offered a smaller variety of interventions, a shorter ‘stay’ and a less varied multidisciplinary team; they were more likely to be provided by voluntary organisations and to have fewer restrictions on the client groups taken on. The most important distinguishing variable was whether services were provided by statutory bodies (NHS) or by voluntary organisations (including joint voluntary/NHS services). The results are shown in Table 2 (numeric variables), Table 3 (categorical variable) and Table 4 (binary variable).

| Cluster | Number of interventions offered from defined list, mean (SD) | Typical length of ‘stay’ in the team, as reported by the manager, mean (SD) | Number of different staff types in the service, mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18.31 (4.936) | 36.81 (18.552) | 7.19 (2.689) |

| 2 | 9.27 (5.781) | 7.18 (3.995) | 2.27 (0.647) |

| Combined | 14.63 (6.884) | 24.74 (20.611) | 5.19 (3.223) |

| Cluster | Services, frequency (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Statutory | Voluntary | Joint statutory/voluntary | |

| 1 | 16 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 2 | 0 (0.0) | 3 (100.0) | 8 (100.0) |

| Combined | 16 (100.0) | 3 (100.0) | 8 (100.0) |

| Cluster | Services, frequency (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Exclusion criteria | No exclusion criteria | |

| 1 | 8 (80.0) | 8 (47.1) |

| 2 | 2 (20.0) | 9 (52.9) |

| Combined | 10 (100.0) | 17 (100.0) |

Model 2

The service provider variable (variable 2) could be considered a ‘swamping’ variable (one that has large differences between categories within it, which may overpower weaker, but substantively interesting, differences in other variables). Therefore, a model was run excluding this variable and including the sixth ranked variable, ‘number of referral sources’.

Services in cluster 1 offered a larger number of different interventions, a longer average length of ‘stay’ and a more varied multidisciplinary staff team; they accepted referrals from fewer sources and were more likely to have restrictions on the types of clients taken on. Services in cluster 2 offered fewer different types of interventions, a shorter ‘stay’ and a less multidisciplinary team; they accepted referrals from more sources and had fewer restrictions about client groups taken on.

Once again, even without including the ‘service provider’ variable, the model produced two distinct clusters, with the most important distinguishing variable being whether services were provided by statutory bodies (NHS) or voluntary organisations (including joint voluntary/NHS services). The results are shown in Table 5 (numeric variables) and Table 6 (binary variable).

| Cluster | Number of interventions offered from defined list | Typical length of ‘stay’ in the team, as reported by the manager | Number of different staff types in the service | Number of referral sources | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| 1 | 16.67 | 6.721 | 33.11 | 20.522 | 6.67 | 2.951 | 2.44 | 1.688 |

| 2 | 10.56 | 5.480 | 8.00 | 3.571 | 2.22 | 0.667 | 12.11 | 4.567 |

| Combined | 14.63 | 6.884 | 24.74 | 20.611 | 5.19 | 3.223 | 5.67 | 5.463 |

| Cluster | Services, frequency (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Exclusions criteria | No exclusions criteria | |

| 1 | 10 (100.0) | 8 (47.1) |

| 2 | 0 (0.0) | 9 (52.9) |

| Combined | 10 (100.0) | 17 (100.0) |

The two resulting typologies aligned with whether or not the ADU was provided by the NHS, and no further typologies were identified in the analysis. Therefore, the descriptive results characterising ADUs are reported separately for NHS-ADUs and for voluntary sector ADUs.

Prevalence of acute day unit services

Forty-five individual ADU services meeting our criteria were identified across England. Of these 45 ADUs, 27 (60%) were provided solely by NHS trusts (17 trusts, 29% of the 58 mental health trusts in England), eight were jointly provided NHS and voluntary sector services (17%) and 10 were voluntary sector services (23%).

The geographical locations of the services identified are shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Map of UK ADU services. Map data © 2019 Google (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA).

In total, 37 of the 45 identified ADU services completed the initial 2016 survey (two declined and six did not respond to multiple requests for information), representing a response rate of 82%. The two ADUs that declined were from the same trust, but the six that did not respond were from different trusts and voluntary organisations. Twenty-two NHS services and 15 joint or voluntary services responded to the survey.

Results are reported separately for NHS services (referred to as ‘NHS-ADUs’) and for joint and voluntary services (referred to as joint/voluntary). As not every survey respondent answered every question, the denominator is given when reporting each result.

Location and access

Most NHS-ADUs (n = 17/22, 77%) were co-located with other mental health services, with the remaining ones on independent premises. Most commonly, NHS-ADUs were co-located with CRTs (n = 11/17), acute inpatient wards (n = 10/17) and community mental health teams (n = 9/17). Several NHS-ADUs were jointly managed with other acute mental health services (n = 13/17). Most NHS-ADUs reported making their own decisions about accepting referrals to their service (‘gatekeeping’) (n = 15/22); in other cases, gatekeeping was either joint with a local CRT (n = 3), or carried out entirely by another team (n = 4).

Very few joint/voluntary services were co-located with CRTs (n = 2/15) (both were joint services), with none being jointly managed, and all gatekeeping their own services.

Purpose of service

In a free-text response to a question asking what the purpose of the service was, 18 of the 22 NHS-ADUs (82%) stated explicitly that their purpose was to provide an alternative to inpatient admission and/or to facilitate early admission from inpatient wards.

All 15 of the joint/voluntary services expressed their purpose as providing support and/or a safe place for those in mental health crisis. In addition, 11 of these 15 (73%) aimed to provide an alternative to admission to inpatient wards and/or accident and emergency (A&E).

Referrals and discharges

The majority of NHS-ADUs accepted referrals from secondary mental health services, CRTs and inpatient wards, with some accepting referrals directly from A&E. NHS-ADUs that accepted referrals from other sources (e.g. primary care) or self-referrals were less common. Nine NHS-ADUs accepted referrals from secondary mental health services only. One NHS-ADU accepted self-referrals from service users or carers. No NHS-ADUs had a completely open access referrals policy. Joint/voluntary services accepted referrals from a wider range of sources, with 6 out of 15 having a completely open access referral policy.

Two NHS-ADUs reported that they rarely referred service users on to other services because typically service users were already using other services as well as the ADU. Two joint/voluntary services also did not refer people on to other services. The remaining services reported a variety of services to which they discharged or referred people, with the majority of both NHS and joint/voluntary services referring on to secondary mental health services (Table 7).

| Referral source | Discharge destination | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHS-ADU, n/22 (%) | Joint/voluntary, n/15 (%) | NHS-ADU, n/20 (%) | Joint/voluntary, n/13 (%) | |

| Self/carer | 1 (5) | 12 (80) | N/A | N/A |

| CRTs | 15 (68) | 11 (73) | 15 (75) | 10 (77) |

| Crisis houses | 3 (14) | 9 (60) | 6 (30) | 5 (38) |

| Inpatient wards | 18 (82) | 8 (53) | 17 (85) | 6 (46) |

| Other secondary mental health services | 16 (73) | 12 (80) | 17 (85) | 12 (92) |

| GPs | 2 (9) | 12 (80) | 12 (60) | 11 (85) |

| IAPT | 3 (14) | 10 (67) | N/A | N/A |

| Other primary care | 2 (9) | 11 (73) | 4 (20) | 6 (46) |

| A&E | 9 (41) | 13 (87) | N/A | N/A |

| Police | 1 (5) | 11 (73) | N/A | N/A |

| Counselling | N/A | N/A | 7 (35) | 12 (92) |

| Welfare advice services | N/A | N/A | 7 (35) | 8 (62) |

| Housing services | N/A | N/A | 6 (30) | 4 (46) |

Client group served by acute day units

Ten of the 22 NHS-ADUs (45%) reported that they had no exclusion criteria. Of the 12 that had exclusion criteria, seven (67%) would not accept people with a diagnosis of dementia. Other explicit exclusion criteria included having a diagnosis of personality disorder (1/12, 8%), brain injury (1/12, 8%), primary alcohol and substance misuse problems (4/12, 33%) and learning disability (3/12, 25%), and being unable to engage with the programme offered (1/12, 8%). Only one NHS-ADU (8%) reported that it excluded those who were actively psychotic or unable to keep themselves or others safe.

Among the joint/voluntary services, the only exclusion criteria were being too intoxicated to engage with the service (4/15, 27%) and being ‘too high risk’ (e.g. having active psychosis) (1/15, 6%). Three services out of the 15 (20%) also excluded those with very severe learning disabilities that would prevent them from engaging.

Nineteen of the 22 NHS-ADUs provided data about the age ranges of the people they worked with. All of these NHS-ADUs worked with service users aged 18–65 years, apart from five older-age NHS-ADU teams that worked only with adults aged ≥ 60 years (23%) and one team that worked only with service users aged 24–65 years (5%). Some teams (6/19, 32%) had no upper age limit; two teams (11%) additionally worked with people aged ≥ 17 years.

Two of the 15 joint/voluntary services worked with people aged ≥ 16 years (13%), with the remaining 13 working with those aged ≥ 18 years (87%). Only one service (5%) had an upper age limit, which was 67 years.

Not all teams responded to questions about service user demographics (which asked for averages over the previous month), but Table 8 shows that, among those that did, the average age of people using NHS-ADUs was higher than that of those using joint/voluntary services. Only three of the joint/voluntary services responded to the question about ethnicity, and two responded to the question about sexual orientation. Among the services that responded, Table 8 shows that the average percentage of service users of different ethnicities and sexual orientations is similar across type of service, with client groups being majority white and heterosexual. These demographics were calculated on the basis of data from the month before the survey was completed.

| Characteristic | NHS-ADU | Joint/voluntary | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/22 teams responding | Median (range) or % | n/15 teams responding | Median (range) or % | |

| Average age (years) | 11 | 48 (28–79) | 12 | 34 (30–46) |

| Female | 16 | 55% | 14 | 68% |

| White | 13 | 77% | 3 | 82% |

| Asian | 13 | 9% | 3 | 8% |

| Black | 13 | 5% | 3 | 1% |

| Mixed | 13 | 4% | 3 | 1% |

| Other | 13 | 4% | 3 | 8% |

| Heterosexual | 10 | 93% | 2 | 79% |

Length of stay

Six of the 22 NHS-ADUs (27%) had no limit on the maximum length of time a service user could use the service. Those that did (73%) had a limit ranging from 10 days to 6 months, with most (12/16, 75%) being between 6 and 12 weeks. The typical length of time with the service ranged from 15 to 84 days, with the median being 30 days (IQR 25–48 days) (18/22 NHS-ADUs responded).

Only three of the 15 joint/voluntary services (20%) put limits on the length of time someone can use the service. One service limited use of the service to 2 hours per visit (but no restriction on the number of visits), one limited users to three visits per referral (but no restriction on the number of referrals) and one service limited use of the service to 10 days. People using these 15 services typically did so for between 1 and 12 days in a month, with a median of 7 days per month (IQR 4–10 days per month) (12/15 services responded).

Caseload

Among the 18 out of 22 NHS-ADUs responding, the total number of places on the caseload available ranged from 6 to 55 (median 25 places, IQR 18–30 places), with between 3 and 45 service users typically visiting the ADU per day (median 15 service users, IQR 11–22 service users).

The annual usage also varied substantially among the 17 out of 22 NHS-ADUs that responded. The median number of service users treated in the previous 12 months was 186 (IQR 138–342 service users, range 114–2000 service users). The median number of distinct treatment episodes provided was 170 (IQR 159–253 episodes, range 120–5544 episodes).

As the joint/voluntary services do not typically keep a ‘caseload’ in the sense that NHS services do, this survey question was not relevant to them. The median number of people using these services per day was 7 (IQR 3–15 people, range 2–20 people), and per year the median was 200 (IQR 100–300 people, range 54–400 people). The median number of periods of care provided by these services was 1874 (IQR 700–4000 periods of care, range 100–6000 periods of care).

Opening hours

Most of the 19 out of 21 NHS-ADUs responding reported opening during the working week, in office hours only, with just two running 24-hour services. The joint/voluntary services were more varied in their opening hours, with two opening during office hours, 10 opening for some period between 12 p.m. and 2 a.m., and three opening from 8 p.m. to 6 a.m. None was a 24-hour service.

Workforce

Table 9 shows the average number of staff members employed by services in various roles (as well as the range of values given and the number of teams that employed staff in each type of role). NHS-ADUs typically employed more nurses, occupational therapists and support workers than any other type of staff, and more qualified clinical staff in general; joint/voluntary services employed more peer support workers and ‘other’ workers, such as staff employed to provide general support to people dropping in to such services. In addition to the roles below, four NHS-ADUs reported having a few hours per week from an arts therapist, and one of those also had time from a music therapist and a dance and movement therapist.

| Type of staff | NHS-ADU | Joint/voluntary service | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of staff, median (range) | Teams employing staff in role (n/22) | Total number of staff, median (range) | Teams employing staff in role (n/15) | |

| Nurses | 3 (1–10) | 18 | 2 (1–3) | 6 |

| Consultant psychiatrists | 1 (1–2) | 13 | 0 | 0 |

| Other medical staff | 2 (1–6) | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| Social workers | 1 (1) | 2 | 2 (1–2) | 2 |

| Occupational therapists | 2 (1–6) | 16 | 0 | 0 |

| Psychologists | 1 (1–2) | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| Graduate mental health workers | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Pharmacists | 1 (1) | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Support workers | 3 (1–10) | 17 | 3 (2–4) | 10 |

| Mental health project workers | 0 | 0 | 10 | 1 |

| Crisis recovery workers | 0 | 0 | 12 | 1 |

| Administrative staff | 1 (1–2) | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| Peer support workers | 1 (1–16) | 3 | 3 (1–13) | 6 |

| Counsellors | 0 | 0 | 2 (1–2) | 2 |

| Students | 1 (1–7) | 8 | 1 | 1 |

| Volunteers | 1 (1–8) | 7 | 6 | 1 |

Interventions provided

A wide range of interventions were provided by services, but no interventions were universally provided. A large majority of NHS-ADUs provided support with medication, physical health, relapse prevention, psychological therapies, daily living activities and one-to-one support. Joint/voluntary services tended not to provide physical or psychological interventions, but all provided one-to-one support, and a large majority provided relapse prevention support. This is shown in Table 10.

| Intervention | NHS-ADU, n/22 (%) | Joint/voluntary service, n/15 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Medication review, prescription and dispensing | 19 (86) | 0 |

| Medication support and monitoring | 19 (86) | 6 (40) |

| Physical health monitoring/investigation | 18 (82) | 1 (7) |

| Self-management/relapse prevention | 18 (82) | 12 (80) |

| Advance directives | 8 (36) | 1 (7) |

| Psychological therapies | 18 (82) | 5 (33) |

| Family work/therapy | 7 (32) | 1 (7) |

| Peer-run groups | 6 (27) | 7 (47) |

| Carer support groups | 9 (41) | 3 (20) |

| Art/drama/music therapy/groups | 7 (32) | 0 |

| Sports groups | 10 (45) | 0 |

| Daily living activities | 19 (86) | 2 (13) |

| Work experience | 2 (9) | 5 (33) |

| Alcohol/substance misuse groups | 11 (50) | 6 (40) |

| One-to-one support | 20 (91) | 15 (100) |

| Debt/benefits/housing help | 15 (68) | 8 (53) |

Service user and carer involvement

Table 11 summarises findings from NHS-ADU and joint/voluntary service respondents on service user and carer involvement in various aspects of the services. A majority of NHS-ADUs involved service users in staff recruitment and had service user forums, and a large majority sought feedback from service users and, to a lesser extent, from carers. Joint/voluntary services had more service user involvement in general, with the majority involving service users and/or carers in management, advisory groups, staff recruitment, collecting feedback (including service users collecting feedback from others) and addressing feedback. A majority also held service user forums and community meetings, and employed peer support workers.

| Activity | NHS-ADU (n/19), n (%) | Joint/voluntary service (n/15), n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Service users | Carers | Service users | Carers | |

| Service management | 2 (10.5) | 1 (5.3) | 11 (73.3) | 6 (40) |

| Advisory groups | 6 (31.6) | 4 (21.1) | 13 (86.7) | 10 (66.7) |

| Staff recruitment | 12 (63.2) | 5 (26.3) | 12 (80) | 6 (40) |

| Staff training | 5 (26.3) | 2 (10.5) | 7 (46.7) | 6 (40) |

| Delivering interventions | 3 (15.8) | 0 (0) | 7 (46.7) | 6 (40) |

| Facilitating groups | 4 (21.1) | 1 (5.3) | 5 (33.3) | 4 (26.7) |

| Feedback about service | 17 (89.5) | 13 (68.4) | 14 (93.3) | 11 (73.3) |

| Collecting feedback | 8 (42.1) | 6 (31.6) | 10 (66.7) | 6 (40) |

| Addressing feedback | 3 (15.8) | 1 (5.3) | 11 (73.3) | 6 (40) |

| Paid positions | 2 (10.5) | 0 (0) | 6 (40) | 0 (0) |

| Peer support workers | 4 (21.1) | 7 (36.8) | 9 (60) | 6 (40) |

| Service user/carer forums | 12 (63.2) | 4 (21.1) | 10 (66.7) | 6 (40) |

| Community meetings | 9 (47.4) | 3 (15.8) | 8 (53.3) | 3 (20) |

Follow-up survey

The follow-up survey in October 2017 identified that five of the NHS-ADU services had closed down (three in one NHS trust and the others in two different trusts), and one had been redesigned to provide a reduced model of ADU care (this was reported to have been done to reduce costs). One new NHS trust had plans to open a pilot ADU, which was to be co-located and managed with an existing CRT. The pilot ADU was due to be opened in early 2018, and, if the pilot site performed well, an additional six ADUs (also alongside existing CRTs) were planned to open later in 2018. At the time of checking, this meant that 23 NHS-ADUs were available, covering 14 NHS mental health trusts (of 58 trusts in total). All of the joint/voluntary services we had identified in the original survey were still operating at this time.

Discussion: mapping and survey

Main findings

The mapping exercise, which identified 45 ADUs in England, demonstrates that ADUs are not an established part of mental health service provision in most areas. The cluster analysis found evidence of two types of service model: (1) NHS services (n = 27) and (2) voluntary sector services (including jointly run NHS and voluntary sector services) (n = 17). Considering the geographical distribution of services (see Figure 2), it is clear that large parts of the population have no access to any kind of acute day service as defined by this survey. Although the evidence base for ADUs is small, there have been positive findings in previous studies (i.e. greater symptom improvement and service user satisfaction than for inpatient wards13), so it is surprising that ADUs are not more widespread.

The difference between the NHS and joint/voluntary services is quite marked. NHS-ADUs are typically available 10 a.m.–4 p.m. on weekdays, with a wide range of interventions (including medication review/prescription/support, physical health, psychological therapies, and help with daily living activities), a multidisciplinary team including clinically qualified professionals, and service users attending for an average of 5 weeks. By contrast, joint/voluntary services tend to consist of supportive staff working in non-clinical capacities, who provide brief, one-off listening and signposting support to those in immediate crisis, often in the evening and the early hours of the morning. NHS-ADUs have less service user/carer involvement in paid roles, management, recruitment and training than the joint/voluntary services. In this regard, NHS-ADUs appear to involve service users and carers at similar levels to CRTs. 8 Although the practical offerings of the two types of service are quite different, the explicitly stated purpose of a large majority of both types is an alternative to inpatient admission. The joint/voluntary services are more often intended as an alternative to A&E, which may explain the difference in daily support offered. There are certainly opportunities for cross-sectoral learning here, and in particular the joint NHS/voluntary sector services could lead on sharing best practice between these different types of service.

It is notable that there are currently no national (or international) standards for how ADUs should be set up or function, and this perhaps explains the variation evident, for example, in the wide range of interventions offered. Unlike for CRTs, early intervention services and assertive outreach teams, no guidance was given in The Mental Health Policy Implementation Guide15 about the composition of NHS-ADUs, resulting in a certain amount of heterogeneity, and no standards or criteria are given by which to assess service functioning. Guidance on the place of ADUs within the acute care pathway is similarly lacking.

The findings of this study are in line with previous research about ADUs, both in England and internationally. For example, a previous survey of psychiatric day hospitals in England found heterogeneity of service provision,16 as did a survey of day hospitals for general psychiatric patients in Germany, England, Poland, Slovakia and Czechia,9 although both studies found that the majority of services aimed to provide an alternative to inpatient admission, similar to the current survey. One aspect we investigated in this survey, namely the involvement of service users and carers in the management and running of ADUs, is lacking in previous research, and there is little indication from international studies that this issue has been addressed elsewhere. It is also unclear from international research whether or not ADUs are provided by the voluntary sector in other countries, as this survey demonstrates they are in England.

NHS-ADUs and CRTs are similar in that both offer a range of interventions, delivered by multidisciplinary teams, as an alternative to admission. The key differences between the services are the location and the timing of contact. Because service users attend a single location during office hours, ADUs are able to offer a wider range of interventions, consistency in terms of the staff service users see, more contact time, and peer support. In comparison, by providing home visits and working shifts, CRT contact time is brief, there is little consistency in which staff member sees which service user, and there is no opportunity for peer support (all of which are well-documented complaints of CRT users17). Although CRTs offer more flexibility in timing and location of care, and the opportunity for the clinical team to observe a service user’s home environment (for people for whom loneliness, isolation and lack of activity are a problem, or whose home environment is problematic), ADU care potentially has added benefits than CRT-only care.

In addition to the differences between NHS-ADUs and CRTs, the two ADU models identified by this survey (NHS and joint/voluntary services) indicate further complexity in the acute care pathway. The different offerings of NHS and joint/voluntary services may explain the geographical overlap evident in Figure 2, with joint/voluntary services ‘filling the gaps’ that NHS-ADUs and CRTs do not cover by providing drop-in services out of office hours. Research into how NHS and voluntary sector services complement each other and work together is currently lacking, although a programme of work is under way to gain insight into this important area. 10

The follow-up survey suggests that NHS-ADU services occupy a precarious position. The closure of five NHS-ADUs in a relatively short time is striking. It implies an unstable environment in which non-mandated services may be seen as easily disposable when there is pressure on resources, despite research evidence suggesting that they can be effective. 12,13 At the same time, the piloting and planned opening of seven new NHS-ADUs in one trust suggests that the value of such units is recognised by some commissioners, which reflects the importance of providing choices for people in crisis. 14

Strengths and limitations

There are two main strengths of this survey. The first is the high response rate (81%), meaning that we can take the results to be broadly representative of existing ADUs in England. The second is the inclusion of all services, whether provided by NHS or by voluntary sector services, which gives a comprehensive picture of what is available, and where.

There are three key limitations. The first is that because ADUs are not mandated services, lacking a definitive name or model, identifying such services was challenging. Although we used a clear and specific definition of the type of team we were interested in, it was frequently the case that one part of a trust would identify no such teams, and then another source within the trust would identify a service that clearly met our inclusion criteria. For this reason, and despite the multiple avenues we used to identify teams, it is possible that there are more ADUs in the country than were identified by this survey.

A second limitation was that, because we found that teams close and open relatively quickly, accurately identifying the number of these services in the country at any one time is challenging.

The third limitation regards the quality of the data obtained in the survey. Many teams did not answer all of the survey questions. In the case of joint/voluntary services this was often because the questions were not relevant, or, as with questions about ethnicity and sexual orientation, because they did not keep records of these variables, but even among the NHS-ADUs some data were missing. The aim was for the survey to be as comprehensive as possible while remaining feasible for busy clinicians to complete, but perhaps a shorter survey would have encouraged a higher completion rate. There is the possibility of social desirability bias from this self-report survey, and that respondents interpreted questions in different ways.

Research implications

The results of this survey demonstrate the need for further research into these services. Although some previous research has compared outcomes for people using ADUs with those for people using inpatient wards,12 there is little evidence comparing ADUs with other non-residential services. The finding12 that ADUs are as effective as inpatient wards is promising, but it would be helpful to investigate the place and effectiveness of ADUs in the wider acute care context. Understanding how the ADU complements other crisis and community provision by increasing the support options available is vital. There is a lack of research considering the acute crisis care system as a whole, and how the range of services available can work together to meet the needs of different people. Investigation of the service user and carer experience of ADUs is also, as far as we can find, entirely lacking, and this is particularly important to rectify. Although this survey was focused on ADUs in England, this is an issue of international relevance, and so comparison with services in other countries would be helpful.

Given that CRTs are widely available as the standard service for non-residential crisis care, it is important to know whether or not ADU provision enhances outcomes for people using acute services. However, the lack of model specification for ADUs and the resulting heterogeneity of services means that in any such research, similar types of service should be considered. Research into the different models of ADU care available, and their relative merits in terms of service user outcomes and experiences, would be beneficial, as would a thorough economic evaluation of the costs and benefits of ADUs in comparison with other acute services. The current Acute Day Units as Crisis Alternatives to Residential Care (AD-CARE) study aims to address these issues.

Implications for policy and practice

A detailed health economic analysis of ADUs would be highly useful for policy-makers and service planners, particularly given the current economic and political climate in the UK. Such an analysis would provide vital information about the best ways to configure services, given the economic pressures that NHS trusts and wider communities find themselves under.

This survey suggests that, on average, around 1215 people use NHS-ADUs or voluntary/joint services per day in England. Putting this in context, as of 2017 there were 18,730 mental health inpatient beds in England. Taking the conservative Marshall12 estimate of the proportion of inpatients suitable for ADUs [23.2%, 95% confidence interval (CI) 21.2% to 25.2%], this suggests that, potentially, approximately 3130 additional service users per day could benefit from ADU care. Given the known pressures on beds, frequent out-of-area placements, and the inherent desirability of offering choice regarding acute care, commissioners and policy-makers should consider the place of ADUs in the acute care pathway. The development of a national policy and the implementation of a standard ADU model would mean that these services would be less vulnerable to closure during economically challenging periods.

For existing NHS-ADUs, it may be worth considering further how former and current service users and carers can contribute to services, and the ways in which voluntary sector ADUs manage this could be of interest to NHS-ADUs. Greater sharing of best practice between services would certainly be desirable, as the heterogeneity of services suggests that this is currently not a regular occurrence.

Chapter 5 Work package 2: case studies

Work package 2 consisted of two parts: WP 2.1, a cohort study of ADU and CRT participants; and WP 2.2, a qualitative study investigating the experiences of ADU staff, service users and carers. Five case study sites were recruited for this part of the project, but one site closed its ADUs within a month of beginning participant recruitment, meaning that this site withdrew from the study. The remaining four sites are included in this report, and each participating ADU is described briefly below.

ADU 1

ADU 1 was located near the centre of a large city with a relatively affluent population (one of the least deprived English core cities according to the 2015 Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD). 18 The ADU opened for a 6-month pilot as we started study recruitment, which was intended to establish the feasibility of rolling out several larger ADUs across the local trust. It was, consequently, a much smaller unit than the others in the study in terms of both caseload (maximum of 10 service users compared with ≈ 30 at the other sites) and physical size.

ADU 1 differed from the other sites in other significant ways. It was jointly run with the local crisis team; it accepted referrals only from the crisis team or inpatient wards, rather than from community teams; it had a group programme constituted of fewer arts-based therapy groups and more psychological groups based on coping strategies and symptom management; and it was the only study ADU to employ peer support workers in a voluntary capacity (each worked at the unit for half a day each week).

The unit was based in an expansive site in a large modern building that also contained mental health wards. The unit itself was tiny – all based off one central corridor – and comprised three communal areas and a garden, without dedicated space for one-to-one work. However, this was a temporary space for use in the pilot, which, if successful, was to lead to a larger caseload and premises. Ultimately, after 12 months of operation, ADU 1 was closed because of trust funding pressures.

ADU 2

ADU 2 was located in an inner-city area, and its catchment area included some of the most socially deprived areas in the country as well as some of the wealthiest. It occupied a freestanding building in the centre of a much larger psychiatric hospital site. There was a crisis house in the same site, users of which were also able to attend the ADU.

The WP 1 survey indicated that people using the service at this site were more likely than those at the other study sites to be from minority ethnic backgrounds, to have problems with practical issues such as housing and debt, and to have diagnoses of severe and enduring psychosis. ADU 2 accepted more referrals directly from the ward than from CRT or community services.

ADU 2 had the most diverse programme of groups among the study sites; auricular acupuncture and aromatherapy were among the available group sessions. It was also the only site to employ dedicated arts therapists, music therapists and dance and movement therapists on a part-time basis.

ADU 2 was the longest-running of the study sites, having been operating as an acute day unit for 15 years. It evolved directly out of, and occupied the same space as, a day hospital operating under an older, more long-term treatment model, which opened in the early 1990s. Several of the staff members had worked there for over 20 years, had seen the transition from a predominantly psychodynamic approach to a more recovery-focused, short-term one, and carried a strong institutional memory of the previous model.

During the study period, ADU 2 was undergoing a period of significant change. The unit lost a significant amount of space, as community teams moved in and occupied rooms that were formerly for ADU use; and for several months there was a threat of closure, until it was decided that the other ADU in the trust would close instead and be incorporated within ADU 2. All of this had an impact on staff morale.

ADU 2 seemed less well attended than the other study sites. At the other sites, the general expectation, and reality, was that all service users on the caseload would attend the unit every day – unless their days were being reduced as part of a planned tapering period – with few exceptions. In the WP 1 survey, the ADU 2 manager indicated that on an average day they would have a caseload of 25 service users, of whom 11 attended and 14 did not attend.

ADU 3

ADU 3 had been open for 7 years and was located in a commuter town outside a medium-sized city; its catchment was largely rural, and included a few other large and small towns. The decline of local industry in the post-war years had led to many of the areas within the team’s catchment area being relatively deprived (as measured using the Index of Multiple Deprivation), particularly compared with the other rural catchment area in the study, ADU 4.

This disparity appeared to be reflected in the budgets afforded to the two teams, as reported in the WP 1 survey: although the two sites had similar caseloads, the annual budget of ADU 3 was half that of ADU 4. It became clear during the study that the work of the team was significantly constrained by budgetary concerns, but this was counteracted by the dedication of the staff team; to raise sufficient funds to buy, for example, basic art supplies, staff conducted a number of fun runs, bake sales and other charitable events in their spare (unpaid) time.

The hospital where the unit was located was originally a general hospital but now focused on mental health; several other buildings were on the hospital site but the ADU was in the main central building, which was grand, dated from the early 20th century, and was built of red brick.

The interior of the unit, however, contrasted sharply with the exterior. The ADU had moved to these new premises from elsewhere on the trust site shortly after the study started. The unit had been freshly refurbished as we started work with it, and was bright, clean and freshly painted. The ADU had a very creative focus, and works of art by service users were displayed throughout.

In keeping with other study ADUs, there was a mix of large rooms used for groups and smaller rooms used for one-to-one work. The unit included a ‘relaxation room’, which was particularly popular with service users; it featured lilac-painted walls, large leather massage chairs and a sound system.

There was also a fully equipped medical clinic, and all service users were given a full physical examination during their first week of attending the ADU. The clinic was also used as a clozapine titration clinic: once per week, service users not otherwise on the ADU caseload attended for clozapine titration. Organising and carrying out this clozapine titration was the responsibility of ADU staff, but they were not resourced to put on extra staff for the occasion, meaning that clinic days were always hectic and drew resources away from the ADU’s primary function.

ADU 4

ADU 4 had been open for 6 years and was located in the commuter belt. Like ADU 3, it was located in a large town and served a largely rural catchment, including small and large towns; unlike ADU 3, the surrounding area was relatively affluent (as measured using the IMD).

ADU 4 reported the lowest proportion of service users experiencing psychosis and served more people with diagnoses of depression or anxiety than the other teams in the study. It was relatively well funded and well staffed; it was the only team to say in response to the survey that staffing felt sufficient.

The ADU site was set back behind some garages on a quiet residential street; the setting was very discreet, and it was impossible to discern the ADU unless actively looking for it. It was part of a larger community site but occupied its own building, which was single-storey and modern. Inside, it was unremarkable but well presented and functional. There was a large group room, a large art room, a common room with a small kitchen, and two smaller rooms that could be used for one-to-one sessions. There was a dedicated garden area where service users could sit and socialise as well as participate in occasional gardening sessions when weather permitted.

Chapter 6 Work package 2.1: cohort study – a comparison of re-admission rates, satisfaction and mental health outcomes in people using acute day units and people using only crisis resolution teams in four localities in England

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Lamb et al. 19 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Methods: cohort study

Design

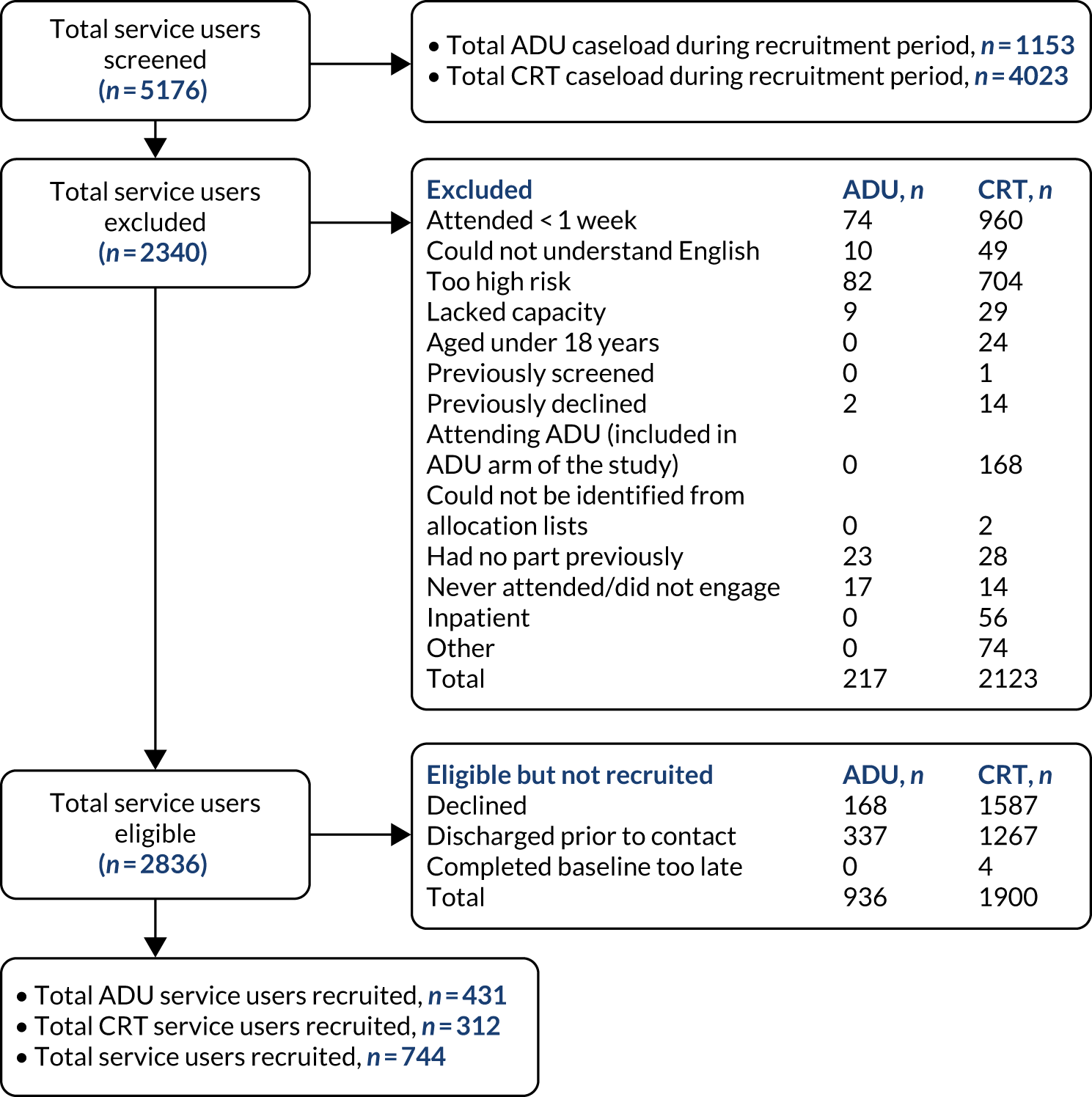

The design was a cohort study of ADU users and CRT users, comparing re-admission rates with those of the acute care pathway during a 6-month period, and satisfaction with services. Five sites with ADUs and CRTs were identified and recruited from the national survey carried out in WP 1, although one site dropped out of the study shortly after starting recruitment, leaving us with four study sites. Recruitment began in March 2017 and was completed by the end of March 2019, with follow-up completed by the end of September 2019. We invited people who were consecutively admitted to each ADU to participate in baseline interviews and then in telephone or online follow-up 8–12 weeks after baseline, with electronic health records (EHRs) outcome data collected at 6 months.

We also invited people from the trusts who used CRTs to participate in the parallel non-ADU cohort.

Objectives

-

To describe the clinical and sociodemographic characteristics of people who use each of the ADUs selected for the in-depth case studies.

-

To determine their pathways into the ADU, length of stay, treatments received, experience, empowerment, loneliness and re-admissions.

-

To compare these characteristics with those of a cohort of people who receive acute CRT care in the same locality but without ADU input.

Setting

Data were collected from ADUs and CRTs in four NHS mental health trusts in England. We investigated the possibility of including a voluntary/joint voluntary–NHS ADU service in the study, but no such units were able to provide the data required to enable a comparison with a local CRT service. Therefore, the study focused on NHS ADUs, as identified by the mapping and survey work of WP 1.

Sample size

We calculated the sample size to detect a 12–13% absolute reduction in the main outcome of re-admissions to the acute pathway at 6 months after baseline (using admission figures from previous research). Our CORE programme grant in crisis teams was powered at 80% to detect a 15% difference between trial arms (50% vs. 35%). Data from London crisis services suggest that baseline re-admission rates could be lower, at 40%. We explored various sample size calculations, including different assumptions regarding this baseline re-admission rate. These showed that 310 people in each arm would afford 90% power to detect differences such as 50% compared with 36.8%, 45% compared with 32.0% or 40% compared with 27.4%. Inflating for a design effect by 30% to accommodate the clustered study design required 400 per arm. These numbers also afforded > 90% power to detect an effect size or difference of 0.3 standard deviations in the client experience measure the CSQ-8 [crisis team mean CSQ 25, standard deviation (SD) 6]. Therefore, we required 400 ADU participants and 400 CRT participants (total n = 800).

Participants

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows:

-

aged ≥ 18 years

-

have used the ADU/CRT service for at least 1 week

-

can read and understand English (or there are translation services in place to enable communication)

-

have the capacity to provide informed consent

-

do not pose too high a risk to others or themselves to participate.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded service users who were too unwell to consent, but otherwise we aimed to be inclusive to gain a fully representative sample, including using local interpretation facilities for people who did not speak sufficient English, when necessary.

Measures

Data were collected from participants using a questionnaire (provided in hard copy or online) at baseline, and another questionnaire 8–12 weeks later, and baseline and 6-month data were collected from EHRs by researchers. The validated measures used in the questionnaire are listed in the next few sections. A full list of the variables included in data collection at each time point is available in Table 12.

| Data source | Time point | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 8- to 12-week follow-up | 6-month follow-up | |

| Questionnaire |

|

|

N/A |

| EHR |

|

N/A |

|

The primary outcome was re-admission for acute treatment during the 6-month study period, which was collected from service use data in the EHRs. After discharge from the service used at baseline, any subsequent use of acute mental health services during the 6-month study period was recorded, along with the duration of each admission to services and any detention under the Mental Health Act (MHA).

The full baseline questionnaire is available in Report Supplementary Material 2, the full follow-up questionnaire is available in Report Supplementary Material 3 and the full EHR data collection schedule is available in Report Supplementary Material 4.

Client Satisfaction Questionnaire – 8-item version

The CSQ-8 was used to collect self-report data on satisfaction with services. The scale has eight items that ask about satisfaction with the mental health service used at baseline, with four response categories indicating low to high satisfaction. Responses are summed to provide a total score, with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction. 20 The scale has evidence of good internal consistency and adequate construct validity. 20

Short Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale

The Short Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (SWEMWBS)21 was used to collect self-report data from participants about their mental well-being. The scale has seven positively worded items, answered in reference to thoughts and feelings over the past 2 weeks, using five response categories (from ‘none of the time’ to ‘all of the time’), and responses are summed to provide a single score, with higher scores indicating better well-being. The scale shows adequate internal consistency and reliability. 21 Increases in scores of 1–3 points are considered to represent clinically meaningful increases in well-being.

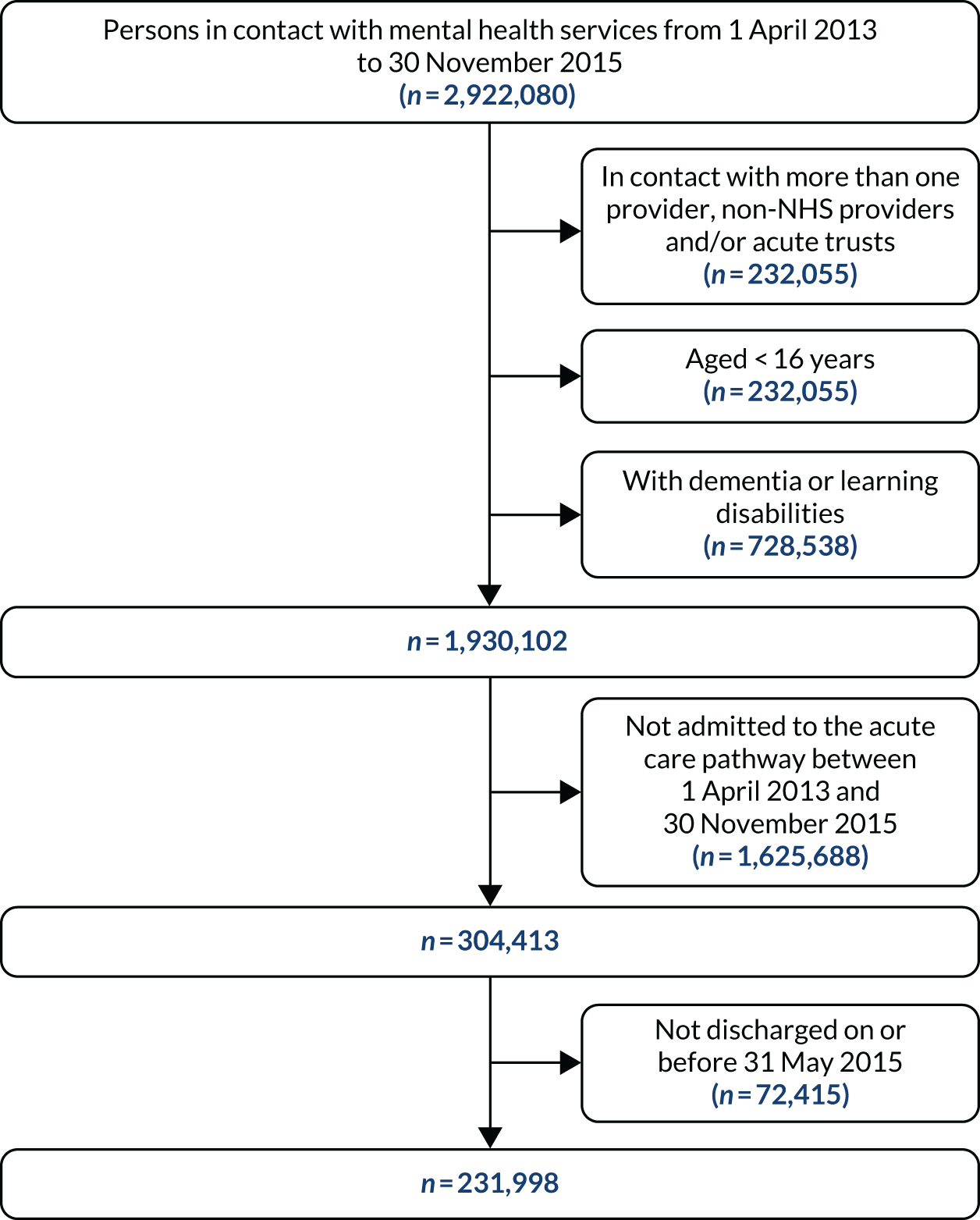

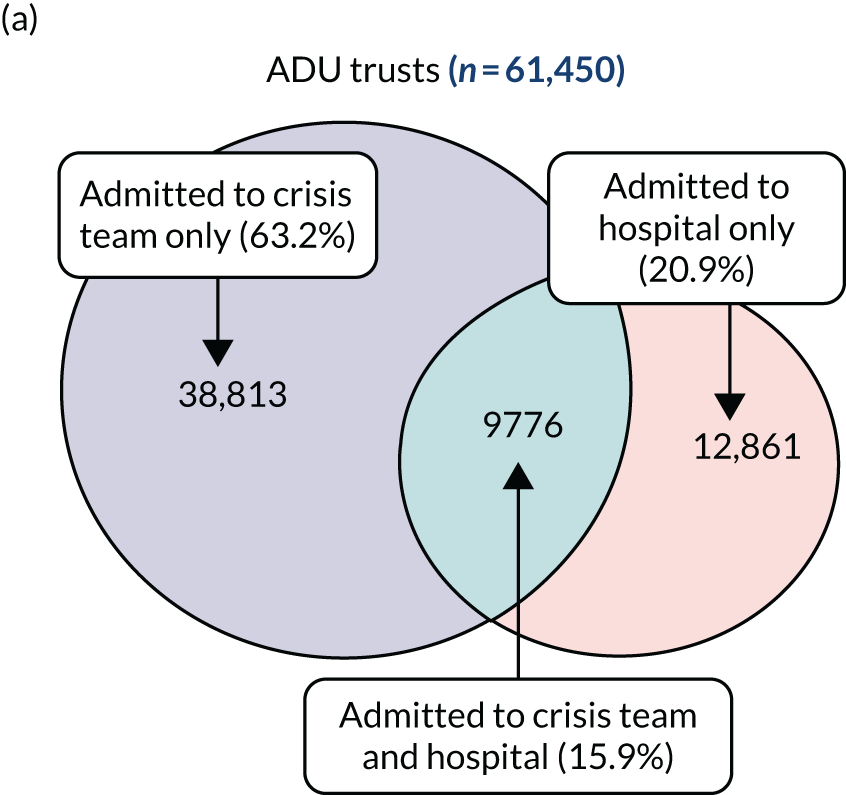

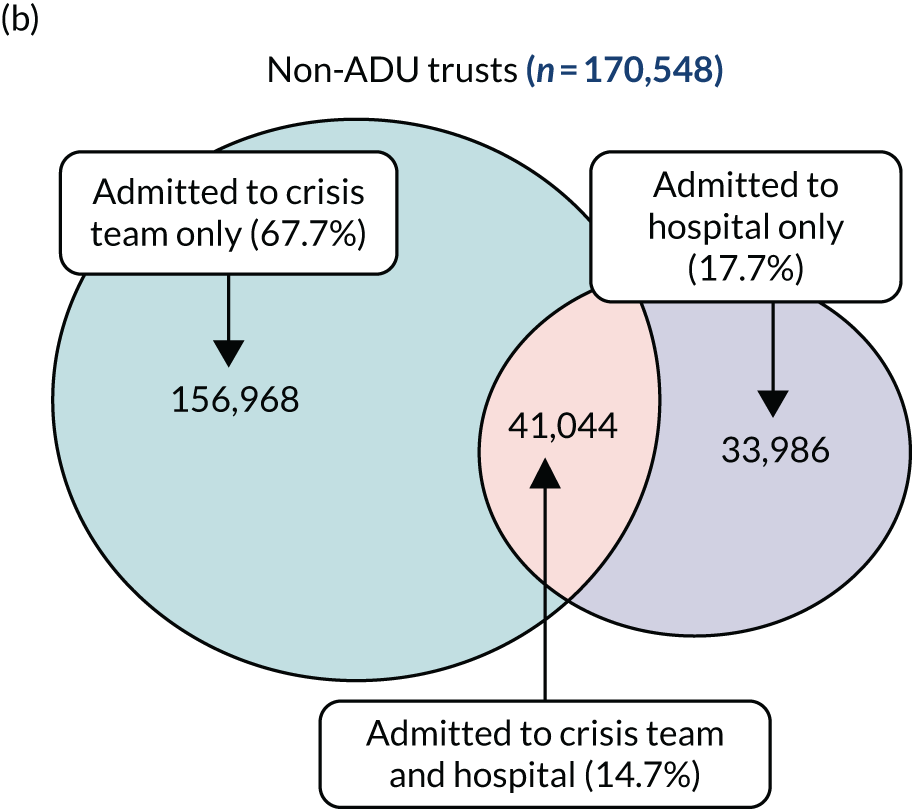

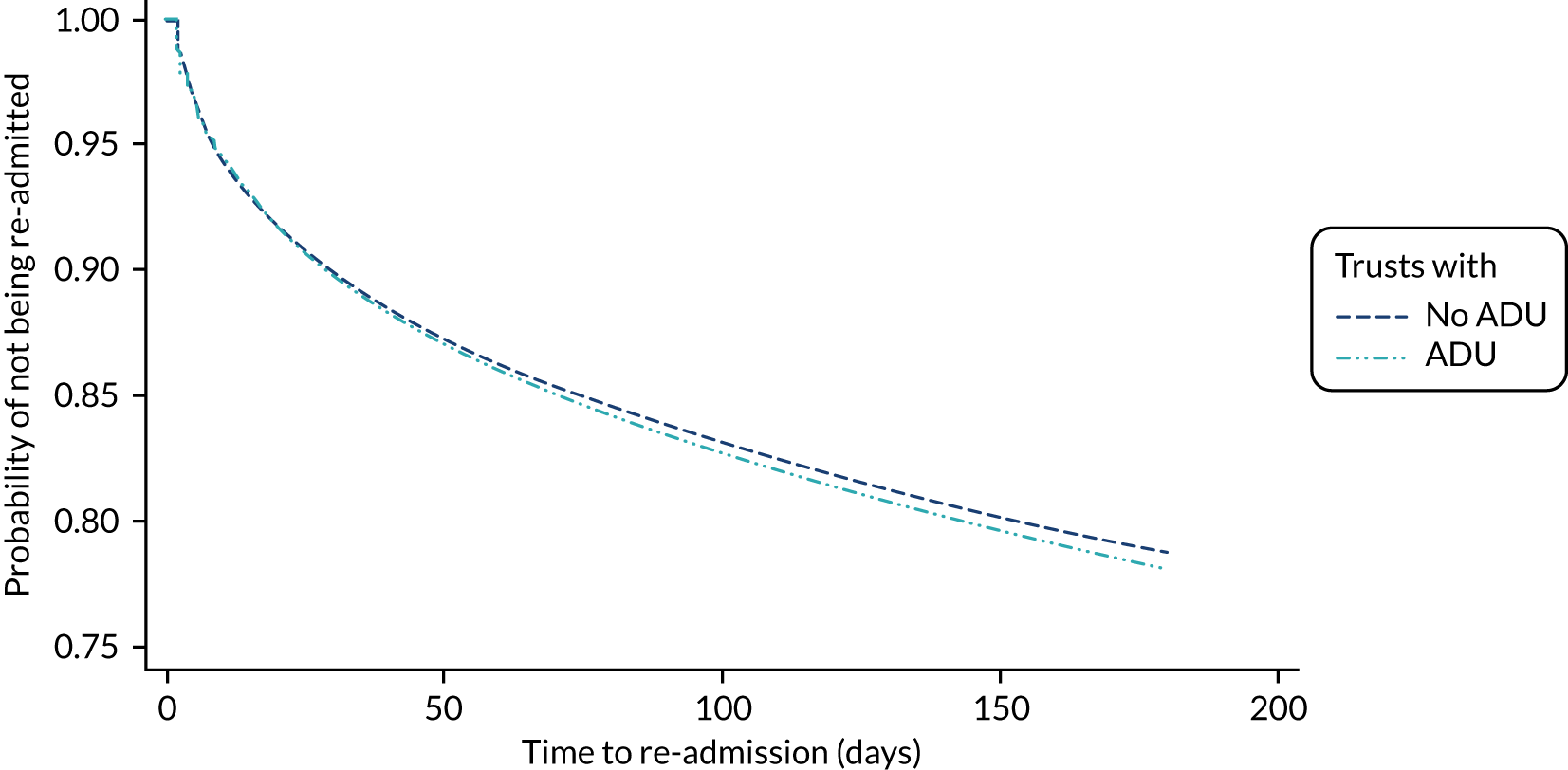

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale