Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 16/41/04. The contractual start date was in March 2018. The final report began editorial review in March 2021 and was accepted for publication in June 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Edwardson et al. This work was produced by Edwardson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Edwardson et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

Sedentary behaviour and health

Sections of this report have been reproduced with permission from Edwardson et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Epidemiological evidence

Sedentary behaviour is defined as ‘any waking behaviour characterised by an energy expenditure ≤ 1.5 metabolic equivalents, while in a sitting, reclining or lying posture’. 2 The health implications of sedentary behaviour have received an increasing amount of attention over the last two decades, and there is now a wealth of epidemiological evidence linking high levels of sedentary behaviour to morbidity and mortality. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses present strong evidence that a greater amount of time spent sedentary is associated with higher all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality rates,3–6 and a higher risk of type 2 diabetes3,4,7 and incident cardiovascular disease. 3,4,8 Moderate evidence exists for a higher risk of total cancer incidence, with incident endometrial, colon and lung cancers being associated with high levels of sedentary time. 4,9,10 Furthermore, for all-cause mortality,6,7,11 cardiovascular disease mortality12 and incident cardiovascular disease,8 there is evidence of a dose–response relationship with sedentary time.

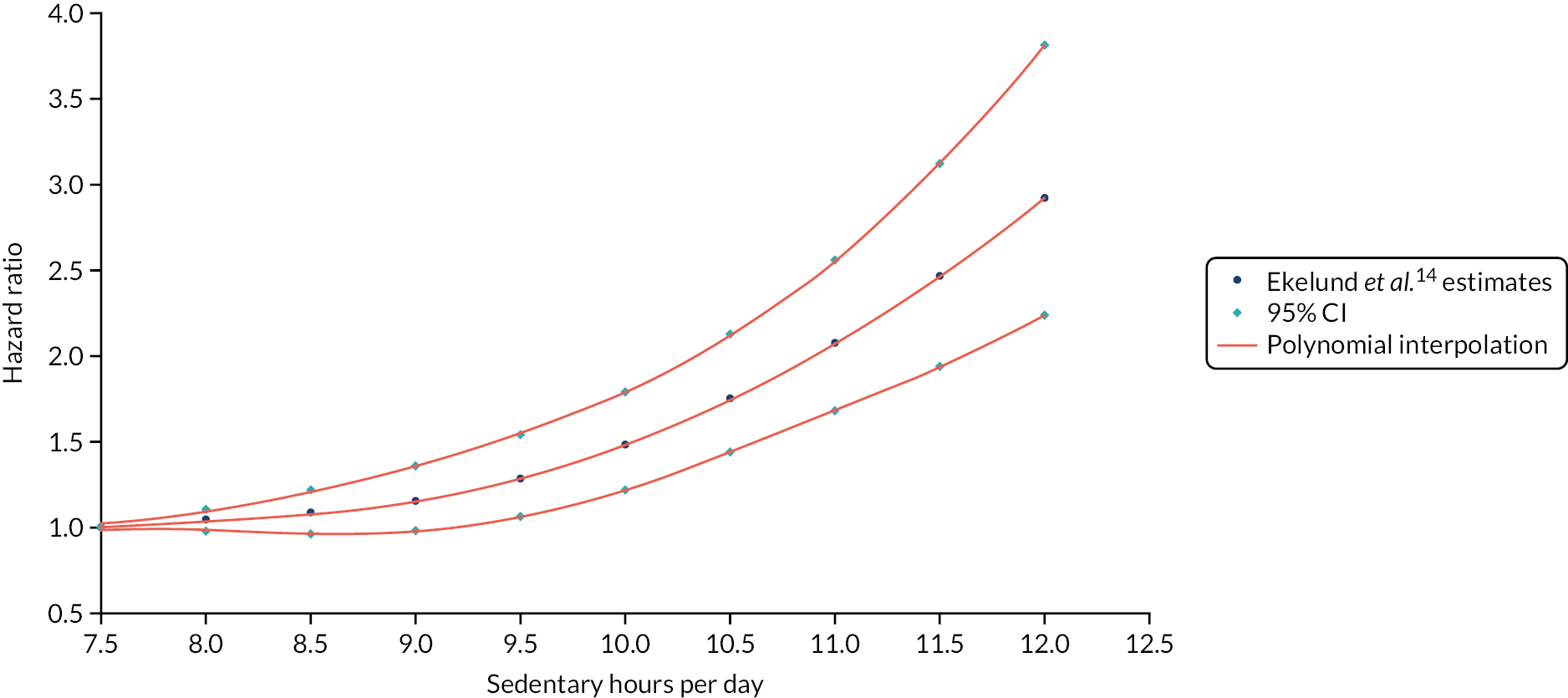

The reported thresholds of sedentary time associated with adverse health outcomes vary depending on the health outcome of interest and sedentary behaviour assessment. Patterson et al. 13 concluded that for adults the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality starts to increase at around 6–8 hours of sitting per day, when sitting time is self-reported. However, another meta-analysis14 with accelerometer-assessed sedentary time suggested that the threshold is slightly higher. Ekelund et al. 14 found that the dose–response relationship between sedentary time and all-cause mortality increased gradually from 7.5 hours of sedentary time per day to 9.5 hours per day, but increased sharply after this. For example, 10 hours and 12 hours of sedentary time were associated with a 1.48 and 2.92 higher risk of death, respectively, compared with 7.5 hours of sedentary time per day. For cardiovascular disease, an increased risk was observed for ≥ 10 hours of self-reported sedentary time per day. 8 It is important to note, however, that emerging evidence suggests that associations with all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality are most pronounced in people who have lower levels of physical activity [i.e. people not achieving the recommended guidelines of at least 150 minutes of moderate or vigorous physical activity (MVPA) per week]. 12,15

In addition to physiological health outcomes, high levels of sedentary time have also been associated with cognitive function16 and mental health (e.g. anxiety,17,18 depression16,19,20 and a lower quality of life16,21). Although limited, in the workplace context there is some evidence to suggest that people with lower levels of sitting have higher work vigour/vitality (i.e. a subscale of work engagement),22,23 higher job performance22 and lower presenteeism. 24

Acute experimental evidence

Acute experimental research consistently shows that breaking up prolonged sitting with short (e.g. 2–5 minutes) but frequent (e.g. every 20–30 minutes) bouts of light-intensity physical activity (e.g. standing, walking, body weight exercises) over the course of a 6- to 8-hour time period reduces postprandial glucose, insulin, triacylglycerol and blood pressure, compared with prolonged sitting with no breaks. 25–28 However, the extent of the attenuation in these risk biomarkers has been shown to be dependent on weight, glycaemic and blood pressure status, sex, ethnicity and fitness level. 25–27,29,30 Females and individuals with a higher body mass index (BMI), impaired glycaemic status, of South Asian ethnicity and a low fitness level experience a worse metabolic response to prolonged sitting compared with their counterparts; however, these individuals also show a greater beneficial glucose and insulin response to regular light activity breaks. 25–27,29,30 Furthermore, the impact of the types of light activity breaks also appears to be dependent on certain characteristics and health markers of interest. For example, breaking up sitting with standing breaks has been shown to reduce glucose and insulin in overweight/obese individuals and individuals with impaired glucose, but not in healthy, normal weight individuals. 25

Prevalence of sedentary behaviour

Data gathered from large studies using accelerometer-based devices show that adults spend approximately 60% (≈9–10 hours/day) of their waking hours sedentary, a figure consistently reported across different countries. 31–33 Over the past 50 years, there has been an increase in sedentary occupations and a decrease in occupations involving MVPA. 34 Coupled with the fact that half of waking hours are spent at work, it is not surprising that working-age adults spend a large proportion of their waking hours and workday sedentary. For example, studies have shown that working-age adults spend between 60% and 70% of their waking day sedentary. 35,36 Likewise, while at work, studies have shown that adults spend around 60–70% of the workday sitting. 35,36 Furthermore, workdays tend to be more sedentary than non-workdays. 37–39

Evidence has also highlighted the key occupational groups that are more sedentary than others, and one such group is office workers. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis, including 132 studies, showed that office workers spend a higher proportion of their day sitting than workers in other occupations, both at work (office workers, 72.5%; other occupations, 49.7%) and during their waking time (office workers, 66.1%; other occupations, 55.9%). 35 Office workers have been shown to spend as much as 70–85% of their time at work sitting,36,40,41 and accumulate a large proportion (40–50%) of this time in prolonged, unbroken bouts. 40,41 These studies identify office workers as an important group for intervention.

Guidelines on sedentary behaviour

The increasing evidence base on the health implications of high levels of sedentary time, along with the now ubiquitous nature of sedentary behaviour, highlights the potential population health impact of this behaviour. This evidence has resulted in physical activity position statements and guidelines now including recommendations on reducing and/or regularly breaking up sedentary time. Examples of these statements and guidelines include the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour,42 the US Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report,7 UK’s Physical Activity Guidelines,43 The 2017 Dutch Physical Activity Guidelines,44 the Australian Government’s Physical Activity and Exercise Guidelines for all Australians45 and the Physical Activity/Exercise and Diabetes: A Position Statement of the American Diabetes Association. 46 Although the sedentary behaviour recommendation statements in these guidelines vary slightly by country, the general message is the same, that is to sit less and minimise prolonged sitting. Furthermore, in 2015, the first expert statement on sitting and standing in the workplace was published and recommended that workers should aim to spend 50% of their workday sitting and 50% upright. 47

Interventions targeting sitting in the workplace

In 2018, an updated systematic review was published, summarising the effectiveness of workplace interventions for reducing sitting time at work. 48 The interventions included physical workplace changes, such as providing height-adjustable desks to enable sitting or standing at work, pedalling workstations and treadmill desks, policy changes, information provision, counselling and computer prompts. Providing height-adjustable desks was the most frequently implemented intervention and was reported as the most promising for reducing sitting time at work, leading to reductions of 100 minutes per workday in the short term (up to 3 months) and 57 minutes per workday in the medium term (3–12 months). Although positive findings were observed, the quality of the evidence was deemed to be very low to low because of a lack of non-biased cluster randomised controlled trials (RCTs), small sample sizes (the majority had 20–50 participants) and a lack of longer-term follow-up. The review by Shrestha et al. 48 highlighted the need for larger cluster RCTs with long-term follow-up.

Our previous intervention: Stand More AT Work

To tackle the high levels of sitting exhibited by office workers, our group developed the Stand More AT Work (SMArT Work) intervention. To address the limitations of previous evaluations, we tested effectiveness of the SMArT Work intervention through a cluster RCT, with follow-up at 3, 6 and 12 months.

The SMArT Work intervention was developed following 12 months of development work, involving focus groups with office workers and managers. 49 The intervention consisted of a brief (≈30 minutes) group-based face-to-face education session, delivered by a member of the research team, which covered evidence on the health consequences of high levels of sitting and prolonged sitting, as well as the health benefits of regular breaks in sitting. At the end of the session, attendees received objective feedback on their own sitting time [collected from an activPAL device (PAL Technologies Ltd, Glasgow, UK) at baseline], which they used to set an action plan and goals to reduce and break up their sitting at work. Attendees were also given an educational leaflet that summarised the key health messages of the group education session, as well as tips for reducing sitting at work. Following the education session, participants received a height-adjustable desk or desk platform (they had the choice within a certain budget of a desk/platform that best suited their office space), with a demonstration from a researcher on how to use it and information on the correct sitting and standing postures while working. This education session was reinforced with a leaflet, which also presented the expert recommendations on how often to change posture (i.e. from sitting to standing and vice versa) during a working day. The recommendations were based on recommendations published by members of our group. 47 Participants were also provided with a Darma smart cushion (Darma Inc., California, USA). The Darma smart cushion was placed on the office chair to track sitting time and to provide feedback on sitting time and prolonged sitting (i.e. bouts ≥ 30 minutes), via a mobile phone application (app). Within the app, participants could (via a user-defined setting) also set the cushion to vibrate following a prolonged sitting bout. The Darma smart cushion provided the participants with an objective self-monitoring device with a participant-determined prompt. Participants were also given posters with messages that were designed to act as a motivator to reduce sitting (and these posters were developed during focus groups). New posters were provided to participants every 3 months. Following each follow-up measurement session, intervention participants were provided with feedback on their sitting time from the activPAL device, which displayed how this time compared with baseline. Every 3 months, participants also received a brief coaching session with a member of the research team, either face-to-face or over the telephone, to discuss progress and barriers and to review goals and action plans.

In the cluster RCT of the SMArT Work intervention,50 at 12-month follow-up, we found that participants who received the SMArT Work intervention sat for 83 minutes less per day during work hours than participants in the control group. 41 The intervention appeared to have many benefits, which included job performance, work engagement, occupational fatigue, sickness presenteeism and quality of life. Despite this success, the process evaluation and results indicated that multiple improvements could be made to maximise both behaviour change and benefits, and this led to the creation of the SMART Work & Life (SWAL) programme, which is an adapted and extended version of the SMArT Work intervention.

Adaptation of the SMArT Work intervention into SMART Work & Life

Based on the RCT results of the SMArT Work intervention, the process evaluation and stakeholder input, we decided on the following adaptations to the SMArT Work intervention for the creation of SWAL:

-

The sitting results from the activPAL device indicated that although participants significantly reduced sitting time at work, the sitting reductions observed for overall daily sitting time suggested that these reductions were driven solely by changes at work and not at home (i.e. no changes were made outside work). These results, therefore, indicated that a whole-day approach to encourage reductions in sitting time was needed, rather than focusing solely on workplace sitting. To reflect this, the SMArT Work intervention was renamed the ‘SMART Work & Life’ intervention and the intervention targeted siting at work and in leisure time.

-

The intervention strategies in the SMArT Work intervention were delivered by a researcher. To enhance sustainability within the workplace, and the scalability of the intervention, workplace champions were trained to facilitate the delivery of the SWAL intervention to participants.

-

In the SMArT Work intervention, participants ranked the brief group-based education session highly in terms of usefulness, increasing awareness and motivating behaviour change, but felt that the session should be longer to cover topics in more detail and allow more time for discussion and sharing. For the SWAL intervention, the initial education session was extended to include possible sitting reduction strategies, barriers faced and overcoming barriers. Furthermore, follow-up group sessions were included to revisit key messages, discuss progress, brainstorm strategies, share what was working and discuss barriers and solutions. Following stakeholder engagement, it was felt that workplace champions would not feel comfortable delivering the initial, more detailed, education session and so this was adapted to an online interactive education session, with the workplace champion facilitating the face-to-face group follow-up sessions, which were less formal.

-

In the SMArT Work intervention, participants felt that the goal-setting and action-planning booklet was too structured and time-consuming. Goal-setting and action-planning was, therefore, revised into a one-page leaflet for the SWAL intervention.

-

Although some participants found the Darma cushion helpful, many struggled with setting up the device on their mobile phones and regular charging was also seen as a barrier. Furthermore, the cushion assisted with only workplace sitting and not overall sitting. In addition, the cushions were also expensive. In the SWAL intervention, the self-monitoring and prompt tools recommended were freely available mobile phone apps, timers and computer software, and this reduced costs and offered participants a choice of options. The online education session in the SWAL intervention included a section on the importance of self-monitoring and prompt tools, and provided step-by-step guides for each of the tools suggested.

-

Participants felt that social support and competitions should be encouraged and facilitated more within the SMArT Work intervention and, therefore, regular sit less and move more challenges were incorporated and facilitated by the workplace champions in the SWAL intervention.

-

Participants valued having progress sessions in the SMArT Work intervention and suggested more ongoing contact and support throughout the programme. As well as the face-to-face group follow-up sessions that were incorporated into the SWAL intervention, the workplace champions also sent out monthly e-mails.

-

There was a lack of management buy-in during the SMArT Work intervention and it was felt that separate educational information was needed for managers.

More details about the SWAL programme can be found in the methods chapter (see Chapter 2).

Building on existing research

The SWAL intervention and its evaluation will advance the current evidence by:

-

being fully powered to detect differences between groups in sitting time (i.e. addresses limitations identified by Shrestha et al. 48)

-

having a robust cluster randomised controlled design (i.e. addresses limitations identified by Shrestha et al. 48)

-

emphasising a ‘whole-day’ preventative approach rather than just focusing on workplace sitting (to address no/limited behaviour change observed outside work hours) and having daily sitting time as the primary outcome

-

incorporating behaviour change maintenance strategies (to prevent the decline in positive behaviour change over the longer term)

-

improving scalability of the intervention by training workplace champions to facilitate intervention delivery, supplemented with online education and freely available self-monitoring and prompt tools

-

including two intervention arms to investigate how important providing a simple, but fairly expensive, environmental change (i.e. height-adjustable workstation) is for reductions in sitting

-

including a cost-effectiveness analysis.

Aims and objectives

The main aim of the study was to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the SWAL intervention (provided with and without a height-adjustable workstation) in a sample of desk-based workers. If both interventions were shown to be effective in comparison with the control group, then a secondary aim would be to determine if one intervention were more effective and cost-effective than the other.

Primary objective

-

To investigate the impact of the SWAL intervention, delivered with and without a height-adjustable workstation, on device-assessed daily sitting time compared with usual practice at 12 months’ follow-up.

Secondary objectives

-

To investigate the impact of the SWAL intervention, delivered with and without a height-adjustable workstation, over the short term (assessed at 3 months) and longer term (assessed at 12 months) on:

-

daily sitting time across any valid day (3 months) and on workdays and non-workdays

-

sitting time during work hours

-

daily time spent standing and in light physical activity and MVPA across any valid day, during work hours and on workdays and non-workdays

-

daily time spent stepping and number of steps across any valid day, during work hours and on workdays and non-workdays

-

markers of adiposity (i.e. BMI, per cent body fat, waist circumference)

-

blood pressure

-

blood biomarkers [i.e. fasting glucose, cholesterol, triglycerides, glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c)]

-

musculoskeletal health

-

psychosocial health (i.e. fatigue, stress, anxiety and depression, well-being and quality of life)

-

work-related health and performance (i.e. work engagement, job performance and satisfaction, occupational fatigue, presenteeism, sickness absence)

-

sleep duration and quality.

-

-

To undertake a full economic analysis of the SWAL programme.

-

To conduct a mixed-methods process evaluation throughout the intervention implementation period (using qualitative and quantitative measures) with participants and workplace champions and to provide insights into the ways in which, and the extent to which, the intervention was implemented, as well as participant experiences of the intervention.

Chapter 2 Methodology

Study design

Shrestha et al. 48 published an updated systematic review on workplace interventions for reducing sitting time at work. The provision of height-adjustable desks was the most frequently used physical change to the workplace from the included studies, and also reported the highest reductions in sitting time at work. However, this systematic review highlighted the lack of non-biased RCTs and studies with larger sample sizes with long-term follow-up. This SWAL trial was a three-arm cluster RCT with a cost-effectiveness analysis and a process evaluation. The SWAL trial was registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number registry prior to recruitment (URL: www.isrctn.com/ISRCTNISRCTN11618007; accessed 6 October 2020). The trial protocol was published in September 2018,1 and the protocol revisions can be accessed via the NIHR Journals Library (URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/phr/164104/#/; accessed 6 October 2020). A summary of the amendments to the protocol are listed in Table 1. A more detailed statistical analysis plan was subsequently signed off before the data analyst had access to the data (see Appendix 1).

| Amendment number | Date approved | Change to protocol |

|---|---|---|

| SA1 | 21 February 2018 | Blood tests to be completed in fasting state |

| SA2 | 9 April 2018 | Additional questionnaires added Clarification of inclusion criteria (0.6 FTE) Clarified job descriptive data to be collected Different point-of-care devices used for blood testing |

| SA3 | 15 June 2018 | Addition of Liverpool City Council Support and strategies for sitting less to be collected at baseline for both intervention and control groups Group catch-up sessions to be voice recorded rather than observed face to face |

| SA4 | 19 March 2019 | Change to recording of adverse events to record only those adverse events that are related to or may impact on the study intervention/outcomes |

| SA5 | 4 September 2019 | The size and number of clusters recruited was different from the anticipated number, therefore, the sample size was updated to reflect this. Dropout rate/non-compliance with activPAL device was increased to 40% |

| SA6 | 28 October 2020 | Owing to the COVID-19 pandemic, 24-month data collection was removed, as it was no longer viable to conduct. Therefore, 12-month data were to be used as the primary end point instead |

Local councils in Leicester, Leicestershire, Greater Manchester and Liverpool, UK, were the target organisations, with defined offices/departments/teams as the clusters and randomised to one of the following three conditions: (1) SWAL only, (2) the SWAL intervention with the addition of a height-adjustable workstation (i.e. SWAL plus desk) or (3) the control group, which continued with usual practice. Outcome measures were assessed at baseline, with follow-up assessments at 3 and 12 months. The study had originally planned to carry out assessments at 24-month follow-up; however, owing to the COVID-19 pandemic, we were unable to complete these assessments. Therefore, the primary end point was revised to 12 months and 12-month data collection was completed by the end of February 2020. The study methods are reported in accordance with the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) statement for cluster RCTs.

Ethics approval and research governance

Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Leicester’s College of Life Sciences representatives and the University of Salford’s Research Enterprise and Engagement Ethics Approval Panel before the commencement of the study. The University of Leicester sponsored the study. All staff and students working on the study completed Good Clinical Practice training. An independent Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) and Trial Steering Committee (TSC) were appointed and met every 6 months during the study. The DMEC included an independent chairperson, one independent academic and a statistician. The TSC included the principal investigator, an independent chairperson, three independent academics (including a statistician) and two council representatives.

Council and participant recruitment

Council recruitment

To recruit councils, we approached contacts at local councils in Leicester, Leicestershire, Greater Manchester and Liverpool to introduce the study. These contacts were from the public health or physical activity and sports departments within each council. After initial meetings and discussions, the study was presented to the respective senior management teams in each council for approval (see Appendix 2 for specific contact and approval details for each participating council).

Participant recruitment

Participants were recruited from the following participating councils: Leicester City Council, Leicestershire County Council, Salford City Council, Bolton Council, Trafford Council and Liverpool City Council. Research teams were based at two study sites in Leicester and Salford. The Leicester research team was responsible for recruitment and data collection at Leicester City Council and Leicestershire County Council, and the Salford research team was responsible for recruitment and data collection at the Greater Manchester councils (i.e. Salford City Council, Bolton Council and Trafford Council) and Liverpool City Council.

Councils were provided with recruitment material to advertise the study (e.g. posters to display on employee noticeboards and wording to include in council communications); however, recruitment strategies were informed by the individual councils themselves (see Appendix 3). All study-related communications disseminated by the councils (e.g. via staff e-mails, staff intranet and weekly newsletters) stipulated that the study sought to recruit office-based employees who spent most of their day sitting. In three of the councils (i.e. Leicester City Council, Salford City Council and Bolton Council), participants were also invited to a briefing event led by a member of the research team. At each briefing event, potential participants were given a participant information sheet and received a detailed presentation about the study, the data collection procedures and the requirement of being involved in the study. At the end of each briefing event, employees were asked to complete an information form and a reply form, which were used to assess eligibility and to identify potential clusters. Participants were grouped into clusters either by a shared office space (could be made up of different teams/departments) or if they were members of the same team but split into different office spaces. To aid cluster development, in the initial stages of recruitment, interested individuals were also encouraged to promote the study within their team to ensure the cluster met the minimum quota of four or more participants prior to randomisation.

To be eligible, each cluster was also required to have at least one participant willing to undertake the role of workplace champion for the cluster if they were to be allocated to one of the intervention arms. Participants were asked to indicate whether or not they would be interested in becoming a workplace champion on the reply form and were, therefore, self-selecting.

Cluster and participant eligibility

Visits to all councils were conducted during the study set up and prior to data collection to understand the different buildings, office locations and set ups, and to inform the definition of a cluster and assist with grouping participants into clusters.

Cluster inclusion criteria

A cluster was required to have four or more participants, including one or more participants who had volunteered to act as the workplace champion. There was no maximum number of participants.

Participant inclusion criteria

Participants were required to meet the following inclusion criteria:

-

office based, aged ≥ 18 years and employed by one of the participating councils

-

spend the majority of their day sitting (self-reported)

-

work for the council at least 60% full-time equivalent

-

willing and able to give informed consent to take part in the study

-

able to walk without the use of an assistive device or requiring assistance form another person.

Participant exclusion criteria

Participants were not able to enter the study if any of the following criteria applied:

-

currently pregnant

-

already using a height-adjustable workstation at their primary work location

-

unable to communicate in English

-

unable to provide written informed consent.

Informed consent

All participants received a copy of the participant information sheet no less than 24 hours before attending a baseline data collection session. At the baseline session, the study details were verbally reiterated, including full details of study procedures, expectations and right to withdraw, and this was carried out by a member of the research team who was suitably qualified and who was authorised to do so by the principal investigator. Written informed consent was obtained prior to any measures being taken.

Allocation arms

Intervention arms

Intervention description

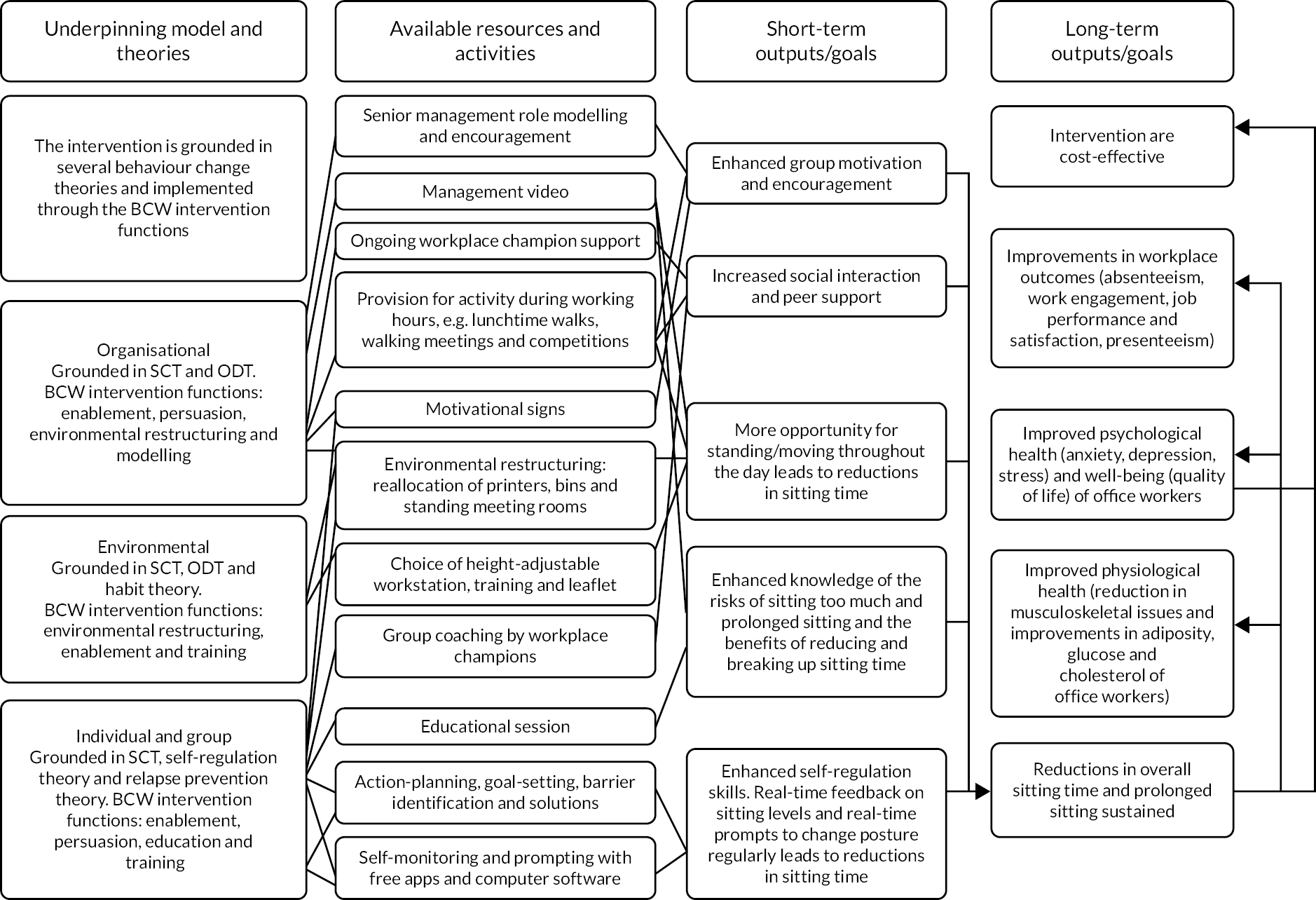

The SWAL intervention is a multicomponent intervention that aims to reduce daily sitting time in office workers. The SWAL intervention is grounded in several behaviour change theories, including social cognitive theory,51 organisational development theory,52 habit theory,53 self-regulation theory54 and relapse prevention theory. 55 The SWAL intervention promotes positive behaviour change through a range of multifaceted strategies (e.g. organisational, environmental, and individual and group). Each of the intervention strategies draws on the principles of the Behaviour Change Wheel and the associated COM-B (Capability, Opportunity, Motivation, Behaviour) approach,56 specifically behaviour guided by the provision of ‘capability’, ‘opportunity’ and ‘motivation’. The logic model summarises the underpinning model, theories and Behaviour Change Wheel intervention functions of the SWAL intervention (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

The SWAL intervention logic model. BCW, Behaviour Change Wheel; ODT, organisational development theory; SCT, social cognitive theory.

Organisational strategies

During the study set-up phase, management buy-in at each of the councils was sought. Support of senior leaders was secured through a series of business case documents and videos, which articulated the importance of reducing employee sitting behaviours, the positive impact this may have on workplace culture and how this may be achieved without disrupting performance and productivity. The programme was also delivered within each cluster in the intervention arms via workplace champions. Workplace champions were all council employees who were enrolled as participants in the study. Workplace champions were invited to attend a 3-hour training session before undertaking the role. The training session was designed to equip workplace champions with the skills and knowledge to implement the intervention. The training programme was designed and delivered by an experienced behaviour change education team and comprised the following eight sessions:

-

Introduction, housekeeping, expectations and concerns

-

SWAL study overview

-

SWAL champions roles and responsibilities

-

Group facilitation – opportunity to practice

-

Intervention fidelity

-

Assessing confidence to be a SWAL champion

-

Next steps

-

Revisiting expectations and concerns.

Following attendance at the training, workplace champions were provided with an electronic folder containing intervention resources, as described in the following sections, and a timeline of implementation (see Appendix 4). (Note that the programme was designed to be delivered over a 24-month period, but was cut short because of the COVID-19 pandemic.)

Environmental strategies

The intervention promoted the small-scale restructuring of the office environment (e.g. relocation of printers, wastepaper bins) to encourage more frequent movement around the office. Participants were also encouraged to think about their home environment. Motivational reminders were embedded into the office environment in the form of visual posters, as well as in a range of computer-based apps (for use both in the office and at home). Behavioural modelling, in the form of the internally based workplace champions, served to demonstrate positive examples within the context of the working environment. The workplace champions circulated monthly e-mails to participating colleagues, the contents of which varied between motivational prompts, hints and tips, and educational material.

Clusters in the second intervention arm also received a height-adjustable workstation that would allow them to transition between sitting and standing postures while working. Participants were able to select their preferred workstation from the following four models: Deskrite 100 (Posturite Ltd, Berwick, UK), Yo-Yo Desk Mini (Sit-Stand Trading Ltd, Swindon, UK), Yo-Yo Desk 90 (Sit-Stand Trading Ltd) and Yo-Yo Desk Go 1 (Sit-Stand Trading Ltd). In addition, participants could choose which colour they preferred (i.e. black or white). All height-adjustable workstations were designed to sit on top of the existing workstation. The desks were delivered to the councils and the facilities team within the councils and/or the study team installed the workstations. Participants were provided with instructions on how to use the equipment appropriately when in the sitting and standing positions.

Individual and group strategies

The intervention included an initial interactive online education session that emphasised the adverse health consequences of excessive sitting and reinforced the benefits of breaking up sitting time and reducing overall sitting time. The session also encouraged participants to estimate their own sitting time at work and at home, encouraged participants to think about strategies to reduce and break up sitting time at work and at home, provided a range of ideas to reduce and break up sitting time at work and at home, and covered barrier identification, goal-setting and the importance of self-monitoring and prompts for behaviour change. Participants were encouraged to download the suggested free smartphone-enabled apps and computer software/extensions and were provided with downloadable ‘how to’ guides. At the end of the education session, participants could download a range of resources, including posters, top tips and an action plan and goal-setting sheet. The workplace champions were responsible for providing participants with a link to the online education session, sending out monthly e-mails (templates were provided), setting sitting less challenges and organising and facilitating group catch-up sessions. Group catch-up sessions were an opportunity for participants to collectively review key messages, brainstorm ideas, discuss any barriers to and facilitators of reducing sitting time, and develop new goals and action plans (an agenda was provided to workplace champions). A copy of the agendas for each session can be found in Appendix 5.

Control arm

Participants in the control arm carried on with their usual working practices. Participants were provided with their results from the baseline and follow-up visits in terms of their anthropometrics, blood pressure and blood biomarkers, and this was the same as the participants in the two intervention arms.

Randomisation

Eligible clusters were randomised to a study arm once all members of the office group had completed the baseline measurements. Randomisation was conducted by a statistician from the Leicester Clinical Trials Unit using a pre-generated list. The statistician was blinded to any identifiable cluster features, with all clusters represented by a unique cluster ID. Randomisation was stratified by area (Leicester: Leicester City Council and Leicestershire County Council; Salford: Salford City Council, Bolton Council, and Trafford Council; Liverpool) and cluster size [small (< 10 people); large (≥ 10 people)]. The study team was responsible for coordinating the deployment of the intervention to workplace champions and were, therefore, unable to be blinded to allocation arm. Likewise, owing to the nature of the intervention, participants were unable to be blinded to the assigned intervention arm.

Sample size

Original sample size

Initial power calculations showed that with a total sample size of 420 participants and 10 clusters per intervention arm the study would have over 90% power to detect a 60-minute difference in average daily sitting time with a two-tailed significance level of 5%. The calculations assumed a standard deviation (SD) of 90 minutes,57 a conservative intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.05,58 a coefficient of variation to allow for variation in cluster size of 0.54 (cluster size range of 15–45) and an average cluster size of 20 participants (based on data from councils that were interested in taking part). The trial was designed to test two intervention arms independently with the control arm, and so to keep an overall significance level of 5% the number of clusters was inflated by a factor of 1.23. 59 The sample size was also inflated by 30% to allow for potential individual loss to follow-up and non-compliance with wearing the activPAL (i.e. the device to assess the primary outcome). A further inflation was applied to allow for one whole cluster drop out per intervention arm. Therefore, the total proposed sample size was 660 participants to be recruited from 11 clusters per intervention arm (i.e. 33 clusters in total). The sensitivity of power was assessed against alternative ICC values of 0.021 and 0.10. 57,58 Adequate power for RCTs is accepted as 80%, and with these ICCs the power was above the required level at 98% and 81%, respectively. In addition, the calculations were based on a similar trial that used an ICC of 0.021 for daily sitting,57 although we chose a more conservative ICC of 0.05.

Re-estimated sample size

At the start of recruitment, the observed average cluster size and variability of cluster sizes were different from those assumed in the original sample size calculation. With the DMEC’s guidance, the sample size was recalculated to ensure that the study was adequately powered. Changing the average cluster size from 20 to 10, the variability in cluster size from 0.54 to 1.42 (cluster size range of 4–38) and the inflation for loss to follow-up and non-compliance with wearing the activPAL device from 30% to 40%, while keeping all other assumptions the same, required 690 participants from 72 clusters.

Study outcome measures

This section defines the primary and secondary study outcomes, and each of the study outcome measures, and when they were assessed, are listed in Appendix 6. The process evaluation methods are detailed in the subsequent section (see Process evaluation methods), and a summary of the sequence and timing of the outcome and the process evaluation measures is shown in Table 2 using a PaT plot. 60 Study measurements were taken at the participants’ place of work by trained researchers. The questionnaire booklet was provided to participants during the face-to-face measurement session; however, participants could take the booklet away with them to complete it in the week following the measurement session, and return the completed booklet at the same time as the activPAL and Axivity (Axivity Ltd, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK) devices.

| Timeline | Study arm | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | SWAL only | SWAL plus desk | |

| Baseline | a , b , c | a , b , c | a , b , c |

| Randomisation | |||

| 3 months | a , b , c , e , f | a , b , c , e , f , g | a , b , c , e , f , g |

| 9 months | g | g | |

| 12 months | a , b , c , f , h | a , b , c , e , f , h , i | a , b , c , e , f , h , i |

| 15 months | g | g | |

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was average daily sitting time across any valid day, measured using the activPAL device, at 12-month follow-up (the primary end point was originally 24 months; however, this was changed to 12 months because of the COVID-19 pandemic).

Accelerometer-measured daily sitting time

The activPAL3 micro device (PAL Technologies Ltd, Glasgow, UK) was used to assess the primary outcome. The activPAL device is capable of distinguishing between sitting/lying, static standing, stepping time and transitions between sitting and standing. 61 At each assessment point, participants were asked to wear the device continuously (i.e. 24 hours/day) for 8 days (i.e. 7 full days plus the assessment day). Using the default manufacturer settings, the activPAL was initialised to record at a sampling frequency of 20 Hz. The device was waterproofed with a nitrile sleeve and applied (by the participant) to the midline anterior aspect of the thigh using a Hypafix transparent dressing (BSN Medical, Germany). Participants were asked to complete a log of the times they got into bed, went to sleep, woke up and got out of bed, as well as indicating which days were workdays and which days were non-workdays, and the start and finish times of each workday during the activPAL wear period. Participants were also asked to indicate whether or not each day was a typical day and if it was not a typical day to the reason why this was the case. In addition, participants were asked to note any times that they removed the device and why. Following completion of the wear period, the devices were collected by the research team, downloaded and visually checked for adequate wear. Where valid data were not obtained, participants were asked to repeat the wear period. Participants who provided an adequate number of valid days received £10 voucher at the end of each data collection time point.

Secondary outcomes

If both interventions were shown to result in a lower daily sitting time than the control arm (i.e. the primary objective), then a secondary objective was to determine if one intervention was more clinically effective and cost-effective than the other. In addition, other secondary objectives were to investigate whether the SWAL intervention with or without a height-adjustable desk (assessed at both 3 and 12 months) led to differences in a range of secondary outcomes, as detailed in the next section.

Secondary activPAL variables

Variables were derived by calculating the average across the number of valid days. The below variables were analysed for the following four different time periods: (1) daily variables (i.e. all waking hours) on any valid day, (2) variables during work hours, (3) daily variables on workdays and (4) daily variables on non-workdays:

-

average sitting time (minutes): total accumulated (3 months) and in prolonged bouts lasting ≥ 30 minutes

-

average standing time (minutes): total accumulated

-

average stepping time (minutes): total accumulated, as well as at a step cadence threshold of 100 steps per minute (in bouts lasting ≥ 1 minute)

-

average number of steps

-

average number of transitions from sitting to an upright posture.

The below variables were also summarised descriptively at each time point and time period:

-

average number of valid days

-

average waking wear time (minutes)

-

average percentage of the day spent sitting

-

average percentage of the day spent standing

-

average percentage of the day spent stepping

-

average percentage of total sitting time spent in prolonged sitting time.

Axivity

Participants were also asked to wear a wrist-worn accelerometer (Axivity AX3; Axivity Ltd) on their non-dominant wrist for 24 hours a day for same 8 days as the activPAL device so that different intensities of physical activity, as well as sleep duration and efficiency, could be calculated. Axivity monitors were initialised with a sampling frequency of 100 Hz, and a dynamic range of ±8 g. Participants were asked to note any time they removed the device on the same log used for the activPAL device.

Anthropometrics and blood pressure

Participants were asked to remove shoes, socks and any outer clothing prior to anthropometrics being taken. Height was measured using a portable stadiometer (Seca Ltd, Birmingham, UK) and recorded to the nearest millimetre. Body weight (kg) and body composition was assessed using the Marsden MBF-6000 Scales (Marsden Weighing Machine Group Ltd, Rotherham, UK) and included measures of weight, BMI and fat percentage. A clothing allowance of 1.5 kg was entered into the scales, along with the participants’ age, gender and height. Waist circumference (cm) was recorded to one decimal place using a standard anthropometric measuring tape (Seca Ltd). Blood pressure was taken using an Omron M3 automated blood pressure monitor (Omron Healthcare Inc., Kyoto, Japan). The participants sat quietly for 5 minutes before three measures of blood pressure were taken, with 1-minute intervals between each measure. The final two measures were used to form an average.

Biochemical measures

Point-of-care testing included measures of HbA1c, cholesterol [i.e. high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and total], triglycerides and fasting blood glucose. Capillary blood samples were collected via the finger-prick method while in a fasted state (fasted for 10 hours). A Quo-Test HbA1c analyser (EKF Diagnostics, Cardiff, UK) was used to measure levels of HbA1c and CardioChek Plus (PTS Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA) for cholesterol triglycerides and glucose.

Self-reported sitting behaviours

Self-reported sedentary behaviours were assessed using an adapted version of the Occupational Sitting and Physical Activity Questionnaire. 62 Participants were asked to estimate the hours that they spent sitting and breaking up sitting during the workday,63 and the percentage of time they spent in the office and what percentage they were based at their desk during the workday. The Past Recall of Sedentary Time questionnaire was used to assess time spent in sedentary behaviours outside work hours in different contexts. 39

Musculoskeletal health

The Standardised Nordic Questionnaire (SNQ), a self-reported measure of musculoskeletal pain, was used to measure musculoskeletal symptoms. 64

Self-report sleep

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index65 was used to assess sleep duration and sleep quality. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index65 consists of four questions relating to sleep duration, plus a further seven questions, measured on a four-point Likert scale, relating to sleep quality.

Mental health, well-being and quality of life

A range of measures were used to assess mental health. Anxiety and depression symptoms were assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale,66 which is a 14-item questionnaire, with seven items relating to anxiety and seven items relating to depression. Responses were scored on a scale of 0–3, with maximum scores of 21 for anxiety and for depression. Participants were also asked to rate their responses to the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS). 67 Measured on a five-point Likert scale, the scores from the PSS were obtained by reverse scoring the four positively stated items (items 4, 5, 7 and 8) and them summing across all scale items. Higher scores on the PSS indicate higher levels of stress. Emotion was assessed via the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule. 68 The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule is a 20-item questionnaire, with 10 items relating to positive emotions and a further 10 items relating to negative emotions. All items were measured on a five-point Likert scale, with separately summed scores for both positive and negative emotions.

The WHO-5 Wellbeing Index was used to measure psychological well-being. 69 The WHO-5 Wellbeing Index consists of five statements (e.g. ‘I have felt calm and relaxed’), with responses marked on a six-point scale. Responses were summed (range of 0–25) and scores were converted to a well-being index (0–100) by multiplying the summed total by four. Higher scores on the WHO-5 Wellbeing Index indicate greater well-being. Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) was measured using The EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L). 70,71 The EQ-5D-5L is a two-part questionnaire. The first part generates a ‘health state’, based on participant responses to each of five health dimensions (i.e. mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression). The ‘health state’ score ranges from 1 to –0.285, where ‘1’ signifies perfect health, ‘0’ death, and negative values have been described as ‘states worse than death’. 72,73 The second part, which asks participants to rate their overall health on a visual analogue scale, is scored between 0 and 100, where higher scores represent greater overall health.

Physical and mental fatigue

The Fatigue Scale,74 an 11-item scale, was used to assess both mental and physical fatigue. The Fatigue Scale is measured on a four-point Likert scale, with total scores ranging between 0 and 33. Higher scores on the Fatigue Scale indicate greater fatigue.

Work-related health and performance

A range of measures were used to assess work-related health. Both job performance75 and job satisfaction76 were assessed using single-item scales. (i.e. How satisfied are you with your job in general?/How well do you think you have performed in your job recently?) Each question was scored on a seven-point Likert scale where higher scores indicated greater performance/satisfaction. The Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES)77 was used to measure work engagement, which consists of nine items. Each item was scored on a seven-point scale and responses were summed to provide an overall score. Higher scores represent higher work-related engagement. Occupational fatigue was measured using the Need for Recovery Scale. 78 Using the Need for Recovery Scale, participants indicated yes or no to 11-item statements (e.g. ‘I find it hard to relax at the end of a working day’).

The Work Limitations Questionnaire was used to measure sickness presenteeism. 79 The Work Limitations Questionnaire comprises eight self-rated questions, measured on a Likert scale. Two items (physical demands) were reversed scored. Responses were converted to percentages (where 0 = limited none of the time and 100 = limited all the time). The demands, control and support scales from the Health and Safety Executive Management Standards Indicator Tool80 were used to establish participants’ perceptions of workload and relations. Sickness absence information was collated via self-report at each assessment point. Absenteeism data were also collected directly from the employer, including duration and frequency of sickness absence 12 months prior to the study, as well as the 12-month study duration.

Social norms, cohesion and support for sitting less

Organisation social norms (e.g. ‘My workplace is committed to supporting staff choices to stand or move more at work’) were assessed via an eight-item questionnaire,57 rated on a five-point Likert scale (from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’). The ‘social community’ subscale of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire-II,81 a three-item questionnaire, using six-point Likert scales, was also used to assess organisational cohesion and support.

Dietary behaviours and alcohol consumption

Questions from the Whitehall II Study82 were used to gather data on dietary behaviours, including snack frequency, frequency of soft drink consumption, fruit and vegetable consumption and alcohol intake.

Health-related resource use

Data on the use of health-related resources were gathered at each assessment point. Participants were asked to provide information on quantity and duration of general practitioner (GP) and nurse practitioner visits, inpatient and outpatient appointments, and visits with other relevant health professionals.

Strategies used to sit less and move more often

Participants were asked to report the frequency of strategies used to reduce sitting behaviours and move more often. 83

Workplace champion characteristics

Workplace champions were asked to complete a questionnaire to collect data on their gender, date of birth, ethnicity, highest level of education, if they supervise staff, how long they have worked at the council, hours worked per week and whether or not they had been a workplace champion at the council previously.

Workplace audit

A cluster representative or a workplace champion was asked to complete an audit of their work environment. Questions related to if the participant’s building had open or closed plan offices or both, hot desking and what the physical environment (e.g. gym access, communal and meeting space with high tables to stand, centrally located bins, information on sitting less displayed) and cultural/policy environment (e.g. written policies on supporting staff to be active, support walking meetings) included.

Accelerometer data processing

activPAL data processing

activPAL data were processed by the principal investigator (blinded). Data were cleaned and processed using a freely available software app called Processing PAL version 1.3 [University of Leicester, Leicester, UK; URL: https://github.com/UOL-COLS/ProcessingPAL (accessed 6 December 2022)]. The validated algorithm in this app separates valid waking wear data from everything else (e.g. time in bed, prolonged non-wear and invalid data). 84 Once data were processed, heat maps were created of the valid waking wear data and invalid data and visually checked for any occasions where the algorithm had misclassified waking wear data, and vice versa. On any such occasion (e.g. early wake time on one day vs. the rest, or early or late sleep time on one day vs. the rest), the self-reported wake and sleep times were compared with the processed data and if this confirmed misclassification then data were corrected. Self-reported logs were also checked for scenarios where data should be removed, for example if the participants removed the device for swimming or it was not a typical day (e.g. some council employees reported working on election days where they had to stand and walk all day). Once this process was completed, summary variables were calculated. A valid activPAL wear day was defined as having ≥ 10 hours wear time per day,85 ≥ 1000 steps per day and < 95% of the day spent in any one behaviour. The first day of data collection was excluded.

To generate data during work hours only, the self-reported start and end of work times for each workday were entered into an excel sheet and uploaded to the Processing PAL app. The Processing PAL app automatically calculated the variables of interest during these specific dates and times. Short (≤ 5 hours) wear time during work hours and long (≥ 12 hours) wear time during work hours were checked against the self-reported logs. A work hours data set was considered valid if it had ≥ 3.5 hours.

Axivity data processing

Axivity data were downloaded in.cwa format using OmGui software (OmGui version 1.0.0.43, Open Movement, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK). All data files were processed through R package GGIR version 1.9-0,86 using R version 4.0.2 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The initial processing of the raw data in GGIR corrects for gravity, periods of non-wear and calculates the vector magnitude of acceleration (Euclidean Norm minus 1 g), using local gravity as a reference and averaged over 5-second epochs. 87 A valid day of daily data was defined as >16-hour detected wear within a 24-hour window, or where there was detected wear for each 15-minute period over a 24-hour cycle. 88 A workday data set was considered valid if it had ≥ 3.5 hours. To generate outcome variables based on a complete 24-hour cycle, the default non-wear setting in GGIR was used. Briefly, invalid data were replaced with mean acceleration values for similar time points from different days for each participant. 88 Acceleration thresholds for light physical activity and MVPA were 40–100 mg and >100 mg (where 80% of a 60-second window exceeded 100 mg). 89

Sleep metrics were derived using an estimated sleep period time window based on sustained inactivity bouts. Estimated arm angles were averaged over 5-second epochs and treated as sustained inactivity/potential sleep periods if the angle change was < 5° over a rolling 5-minute window. 88 The first and last night were removed because of the recording period starting and ending at midnight, likely meaning only part of the sleep window would have been captured. Visual reports were generated and compared for accuracy against participant diaries. Obvious inaccuracies in the predicted sleep window based on viewing the data resulted in the removal of the window altogether. 88

The variables below were derived by calculating the average across the number of valid days. The variables were analysed in the following four different time periods unless specified: (1) daily variables on any valid day, (2) variables during work hours, (3) daily variables on workdays and (4) daily variables on non-workdays. The variables were as follows:

-

average time spent in light physical activity (minutes)

-

average time spent in MVPA (minutes) in 1-minute bouts

-

average sleep duration (minutes) calculated daily for workdays and non-workdays

-

sleep efficiency (%), defined as the ratio of time an individual is asleep to the total time the individual has spent in bed, calculated daily for workdays and non-workdays.

The average number of valid days and wear time (minutes) were also summarised descriptively at each time point and time period.

Process evaluation methods

A full process evaluation was carried out to provide insight into the observed outcomes and to contribute towards the understanding of the mechanisms of the SWAL intervention components. More specifically, the main areas to assess were recruitment, intervention implementation and participation, intervention sustainability, intervention contamination and unexpected events arising from the intervention and study. Methods comprised a range of questionnaires, focus groups, interviews and observations. The process evaluation plan can be found in Appendix 7.

Intervention fidelity

The fidelity of the intervention was monitored through several methods. First, via a questionnaire to individual participants at the 3- and 12-month time points, which asked about engagement with each intervention activity. Second, via an intervention timeline submitted by the workplace champions at the 3-, 9- and 15-month time points (note that this was collected earlier than 15 months in some councils once we knew that the study was going to use the 12-month follow-up as the primary outcome because of the COVID-19 pandemic; however, some councils had passed the 15-month stage and had, therefore, already submitted the documents). Workplace champions were required to indicate the date each task had been completed from a list of intervention activities. Third, the group catch-up meetings, led by the workplace champions, were audio-recorded. All recordings returned by champions were assessed to ensure that the content delivered was representative of the group catch-up agenda issued.

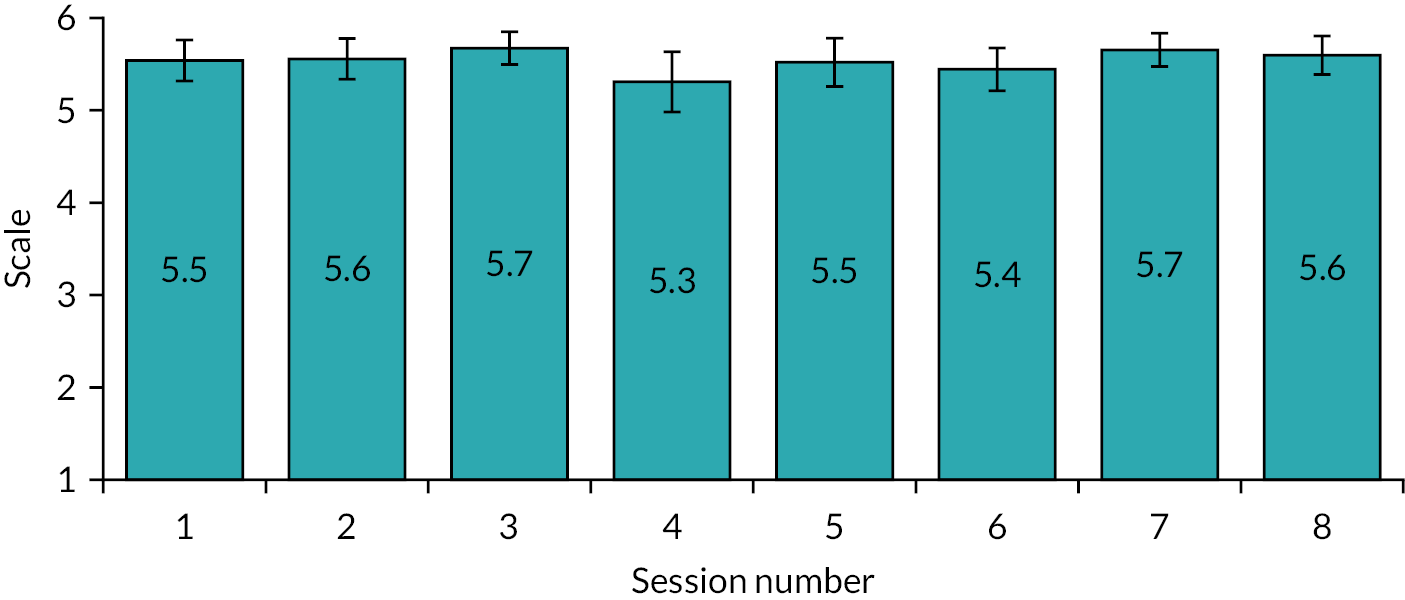

Group catch-up session fidelity

Group catch-up sessions were evaluated using an assessment tool designed specifically for this study. A copy of the tool is provided in Appendix 8. The aim of the assessment tool was to address each element as specified in the group catch-up session agenda (see Appendix 5). The assessment tool consisted of nine components in total (five components for catch-up session 1 and four components for catch-up session 2) (Table 3).

| Section | Group catch-up session | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |

| 1 | Introduction An outline of the catch-up session |

Introduction An outline of the catch-up session |

| 2 | Your story Opportunity to share what’s been going well and what’s not going well Share strategies or tips and any benefits experienced Identify solutions for barriers |

Your story Opportunity to share what’s been going well, what’s not going well – at work and outside work Set a group plan to help continue reducing sitting time at work |

| 3 | Refresher of key messages Revisit key messages from the online education session Discuss ideas to do at work as a group to reduce sitting time Discuss ideas to do outside work and how to get family and friends involved Remind group to visit resources available on the e-learning platform |

Slip-ups and relapse Information about slip-ups and relapse, definitions and their role in behaviour change Explore situations that could increase the risk of slip-ups or relapse and identify strategies Reflect and make a plan for any possible future slip-ups or relapse |

| 4 | Goal-setting/action-planning Reflect on past goals Revisit importance of setting goals and a reminder to set new ones |

Next steps Information on next session |

| 5 | Next steps Information on next session |

|

Workplace champions verbal behaviours

The workplace champions received training on the content of the group sessions and also on how to use interactive techniques derived from the motivational interviewing approach. 90 These skills included techniques such as Open-ended questions, Affirmations, Reflections, and Summaries (OARS). 91 In addition to the content components, it was important to assess the core micro-skills and, therefore, a component on OARS was also added to the assessment tool (see Appendix 8). Each component in the assessment tool was rated as ‘present’ (i.e. the behaviour was observed more than once), ‘absent’ (i.e. the behaviour was not observed) or ‘attempted’ (i.e. the behaviour was observed only once). Duration of the group catch-up sessions was also noted.

Inter-rater reliability of audio-recordings

To assess inter-rater reliability (IRR), 11 (20%) audio-recordings totalling 233 hours were tested by two coders. A third coder was involved in discussions to ensure that discrepancies were addressed and the tool was refined.

Data analysis

Inter-rater reliability was analysed using SPSS (version 25.0; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) to generate Kappa scores within the cross-tabulation function. Kappa levels range from –1 to 1, with a Kappa level >0.60 indicating adequate agreement among raters. A percentage agreement level of ≥ 80% was used as the minimum acceptable inter-rater agreement.

The assessment tool data were analysed using Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) to calculate the number of ‘present’, ‘attempted’ and ‘absent’ scores across different components. Data were also analysed to compare intervention arms (i.e. the SWAL-only and SWAL plus desk arms). Levels of adherence for specific components were categorised as high, moderate and low fidelity if they fell within the 80–100%, 51–79% and 0–50% ranges, respectively.

A chi-squared test was carried out to determine if there were differences in scoring between the two study intervention arms (SWAL only vs. SWAL plus desk) at the two catch-up sessions. Duration of the group catch-up sessions was analysed using Microsoft Excel and was based on the time reported by the two raters and then categorised as within time or over time.

Workplace champion feedback

The perceptions of intervention delivery by workplace champions were assessed with a questionnaire at 12 months. This contained open-ended questions exploring what elements of the programme the workplace champions felt had or had not worked well. Workplace champions were also invited to take part in a telephone interview to further explore their experiences of being a workplace champion. Telephone interviews were audio-recorded and later transcribed verbatim.

Office observations

Office observations were conducted in a sample of intervention and control clusters. Clusters were split into groups based on the council, the cluster size [small (< 10 people) or large (≥ 10 people)] and randomisation arm. One cluster was randomly selected to be observed in each group at the 3- to 6-month and 12- to 15-month time points. The observation period was approximately 2 hours long and sought to identify the integration of behaviours based on the normalisation process theory framework. 92 The observer recorded written notes on the use of height-adjustable workstations (for participants in the SWAL plus desk group), sitting and standing time, engagement with colleagues, office structure, and patterns of office-based encounters. Control group clusters were observed in the same manner to maintain consistency.

Evaluation questionnaire

All participants were issued with a process evaluation questionnaire at the 3- and 12-month time points. The questionnaire included a combination of scaled and open responses. The sections of the questionnaire were as follows:

-

online education feedback

-

workstation feedback

-

apps/computer software feedback

-

alternative support

-

group catch-up session feedback

-

sitting less challenges/competitions feedback

-

strategies to sit less

-

barriers to sitting

-

other lifestyle changes

-

health assessments.

Control group participants also received a questionnaire that enquired about any lifestyle changes that may have influenced their sitting time, and the impact that attending the study health assessments may have had on their behaviour.

Focus groups

Participants were invited to take part in focus groups at the 12-month time point. Separate focus groups were held for each intervention arm and the control group. Discussion was facilitated using a semistructured topic guide, covering the following themes: reasons for taking part, impact of measurement sessions on behaviour, views on intervention components, and benefits of and barriers to sitting less. Participants allocated to the SWAL plus desk arm were also asked about their experiences of their height-adjustable workstation use. Discussion for control participants was focused on reasons for taking part, organisational support for study activities, impact of measurement sessions on behaviour, lifestyle changes and any contact they may have had with intervention participants. Focus groups were audio-recorded and later transcribed verbatim.

Analysis of process evaluation questionnaire, focus groups and interviews

Analysis of the focus groups and interviews was informed by principles of the constant comparative approach. 93 Briefly, a sample of transcripts were read and re-read to begin the process of identifying initial themes and the relationship between themes (in an inductive manner), and this was translated into an initial coding framework. Transcripts were then uploaded to NVivo (QSR International, Warrington, UK) to facilitate the process of systematic coding of transcripts. The coding framework was refined and expanded throughout the coding process, adding new codes, refining the names of codes and amending relationships between codes. Free-text responses from the process evaluation questionnaire were uploaded to the same NVivo file to enable coding with the same framework. After a phase of open coding, a set of questions (derived from the aims of the process evaluation) informed the addition of further codes, and further coding of the transcripts (bringing in a more deductive element). Data coded to each relevant code were retrieved and re-read to identify patterns and ‘weight’ of findings to enable summaries to be produced.

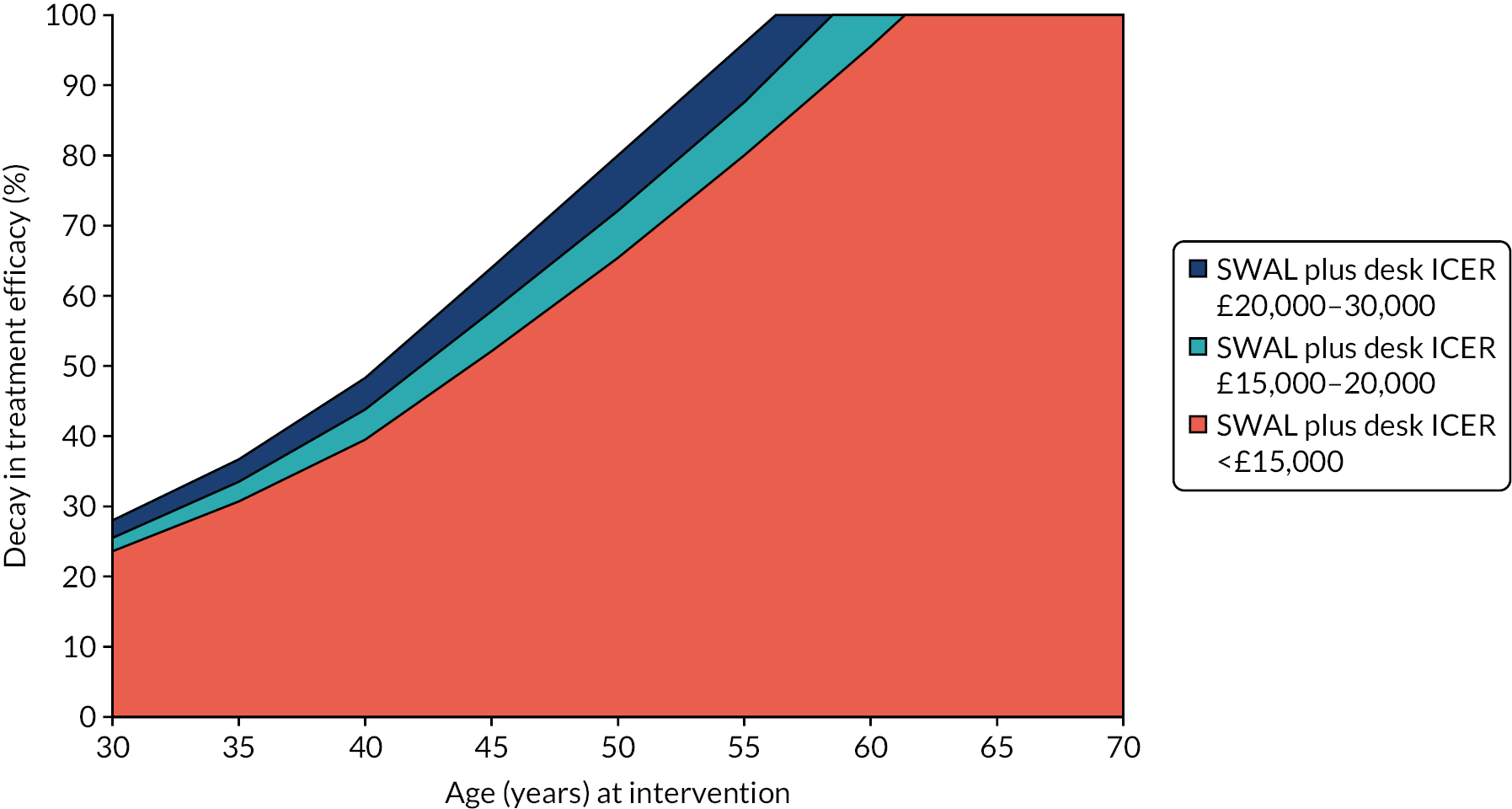

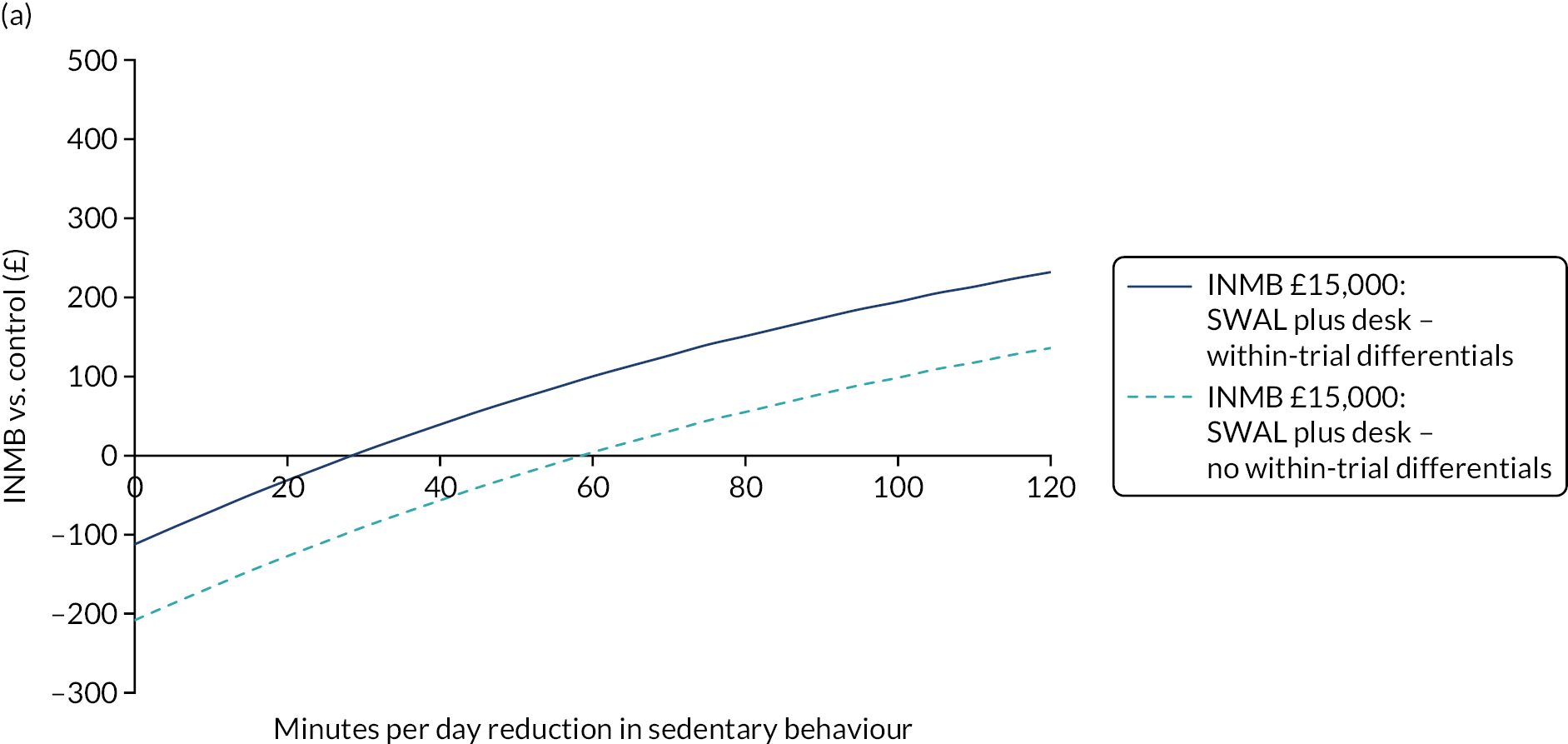

Cost-effectiveness

Full details of the methods for the cost-effectiveness analysis are presented in Chapter 5. In brief, the economic evaluation assessed whether or not the SWAL intervention, with and without a height-adjustable workstation, was cost-effective compared with usual practice. To address the question of cost-effectiveness, the economic analysis of each SWAL intervention comprised the following:

-

a descriptive assessment of resource use, costs and outcomes

-

a cost-effectiveness analysis with costs and outcomes estimated within the trial period and extrapolated into the longer term

-

a series of sensitivity, scenario and threshold analyses considering the impacts of key uncertainties on base-case findings

-

a secondary cost-effectiveness analysis based on observed differences between secondary outcomes within the trial period.

Outcomes included quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), in line with current UK guidance for economic evaluations. 94 Secondary outcomes included other measures of health, well-being and productivity. The analysis was performed initially from a public sector perspective, with an employer’s perspective subsequently considered. The base-case cost-effectiveness analysis extrapolated differences observed in the trial period into the longer term. Results over the trial’s time horizon (i.e. 12 months) are presented for comparison. Cost-effectiveness results are expressed in terms of incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs), showing the incremental cost per additional QALY compared with the other strategy, incremental net health benefits (INHBs) to show the difference between the health generated with a strategy and the health that could be generated elsewhere in the health-care system using the same resources, and incremental net monetary benefits (INMBs) to present the monetary value of the additional health generated, at thresholds of £15,000, £20,000 and £30,000 per QALY. 94 Scenario, sensitivity and threshold analyses were conducted across a variety of domains (participant characteristics, intervention costs, methodological approaches, model assumptions, etc.) to explore the uncertainty around the economic findings.

The COVID-19 pandemic

In March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic led to the UK Government issuing guidelines on social distancing and restrictions on non-essential travel. As part of these measures, employees were encouraged to work at home, where possible. 95,96

COVID-19 Work Transport and Health Behaviours Questionnaire

In the light of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the UK Government-imposed restrictions that occurred in March 2020, SWAL participants were invited to complete an additional optional short online survey to identify any changes in peoples’ daily lifestyle behaviours relating to working practices, sitting and physical activity behaviour, and health, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The online survey was created on the Jisc online surveys platform (Jisc, Bristol, UK), which is a General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)-compliant online survey tool designed for academic research, education and public sector organisations. A participant information sheet and a consent statement were included on the opening page of the survey. Ethics approval was gained from University of Leicester’s College of Life Sciences representatives and the University of Salford’s Research, Enterprise and Engagement Ethical Approval Panel.

The link to the questionnaire was issued to participants via e-mail at the beginning of May 2020. The following measures were included in the questionnaire:

-

geographic location, gender, age group and ethnicity

-

household composition and number of dependents

-

details of any caring and home-schooling responsibilities

-

changes in working situation (working from home/furloughed, etc.)

-

changes in ways of working (use of virtual meetings, etc.)

-

changes in time spent sitting, standing, moving and in physical activity

-

types of physical activity engaged in pre- and post-COVID-19 restrictions

-

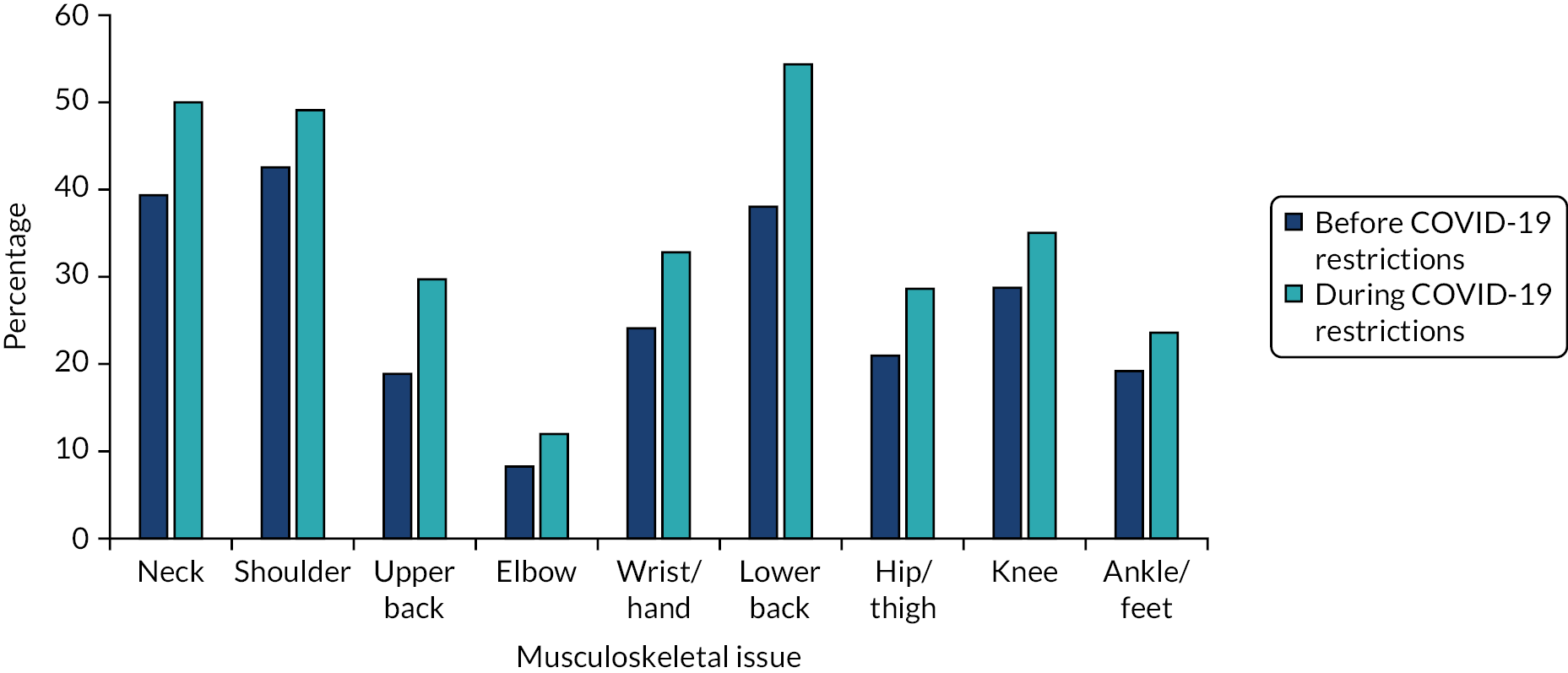

musculoskeletal problems (measured using the SNQ)

-

sleep duration (measured using a short version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index).

Lifestyle behaviour questions were adapted slightly in wording to ask about lifestyle behaviour prior to the COVID-19 restrictions and since/during the COVID-19 restrictions.

Analysis of the COVID-19 questionnaire

Data were downloaded from the Jisc platform and imported into Stata (Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX, USA), where all data cleaning, reduction and analysis was carried out. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests and paired t-tests were carried out to compare the physical and lifestyle behaviours before and during COVID-19 restrictions.

Statistical analysis

Cluster- and participant-level baseline characteristics were summarised by randomisation group and for all participants (total). We also carried out a descriptive comparison of baseline data between completers (i.e. participants who provided valid activPAL data at baseline and at 12 months) and non-completers, within randomisation groups and overall.

Analysis of the primary outcome

The primary analysis was performed using a linear multilevel model. Analysis of covariance was used with each participant’s sitting time at 12-month follow-up as the outcome variable, adjusting for sitting time at baseline and for the average waking wear time across baseline and 12-month follow-up. The model also included a categorical variable for randomisation group (control group as reference) and terms for the stratification factors (i.e. area and cluster size). Office clusters were included as a random effect to model worker heterogeneity within office sites. The structure of the variance–covariance matrix for the random effect was assumed to be identity and the models were estimated using restricted maximum likelihood.

For the primary analysis, missing data were not replaced (complete-case analysis) and participants were included in the intervention group in which their cluster was randomised, irrespective of the intervention that was actually received.

For both comparisons (i.e. SWAL-only group vs. control group; SWAL plus desk group vs. control group), the estimate of the difference between intervention group and the control group for average daily sitting time at 12 months and the corresponding 97.5% confidence intervals (CIs) (to adjust for multiple testing – two-treatment arm comparisons) and p-values are presented. Statistical tests were two sided. Furthermore, the ICC and 95% CI were estimated to assess the strength of the clustering effect.

Secondary analyses

A secondary analysis was carried out to evaluate if one intervention was more effective than the other. The secondary analysis used similar methodology to the primary analysis; however, there was no formal adjustment for multiple significance testing, as this was an unpowered analysis. Estimates are presented with 95% CIs and p-values. Statistical tests were two sided.

Secondary outcomes

A restricted set of key secondary outcomes (i.e. sitting time, prolonged sitting time, standing time and stepping time – daily and on workdays and during work hours calculated from the activPAL data) were analysed using similar methodology as the primary outcome analysis; however, no corrections were made for multiple testing.

Given the number of secondary outcomes, all of the other secondary outcomes were summarised descriptively by intervention group.

Sensitivity analyses

The sensitivity analyses were conducted using similar methodology as the primary analysis of the primary outcome; however, there was no formal adjustment for multiple significance testing. The sensitivity and subgroup analyses were conducted for daily average sitting time at 12 months and average sitting during work hours at 12 months only. All tests and reported p-values were two sided. Estimates are presented with 95% CIs, with the exception of the primary analysis of the primary outcome, which is presented with 97.5% CIs.

Per-protocol analysis

The effect size was also estimated using a per-protocol analysis. The per-protocol analysis excluded the following participants:

-

participants who did not provide valid activPAL primary outcome data at baseline or at 12-month follow-up

-

control group participants with access to a standing desk at 12 months

-

participants in clusters belonging to the intervention arms who did not have a workplace champion assigned or the champion left their role within the first 3 months

-

participants who were out of their window for 12-month follow-up in terms of their activPAL data (± 2 months)

-

participants who did not spend the majority (>50%) of their day sitting at baseline as measured by activPAL.

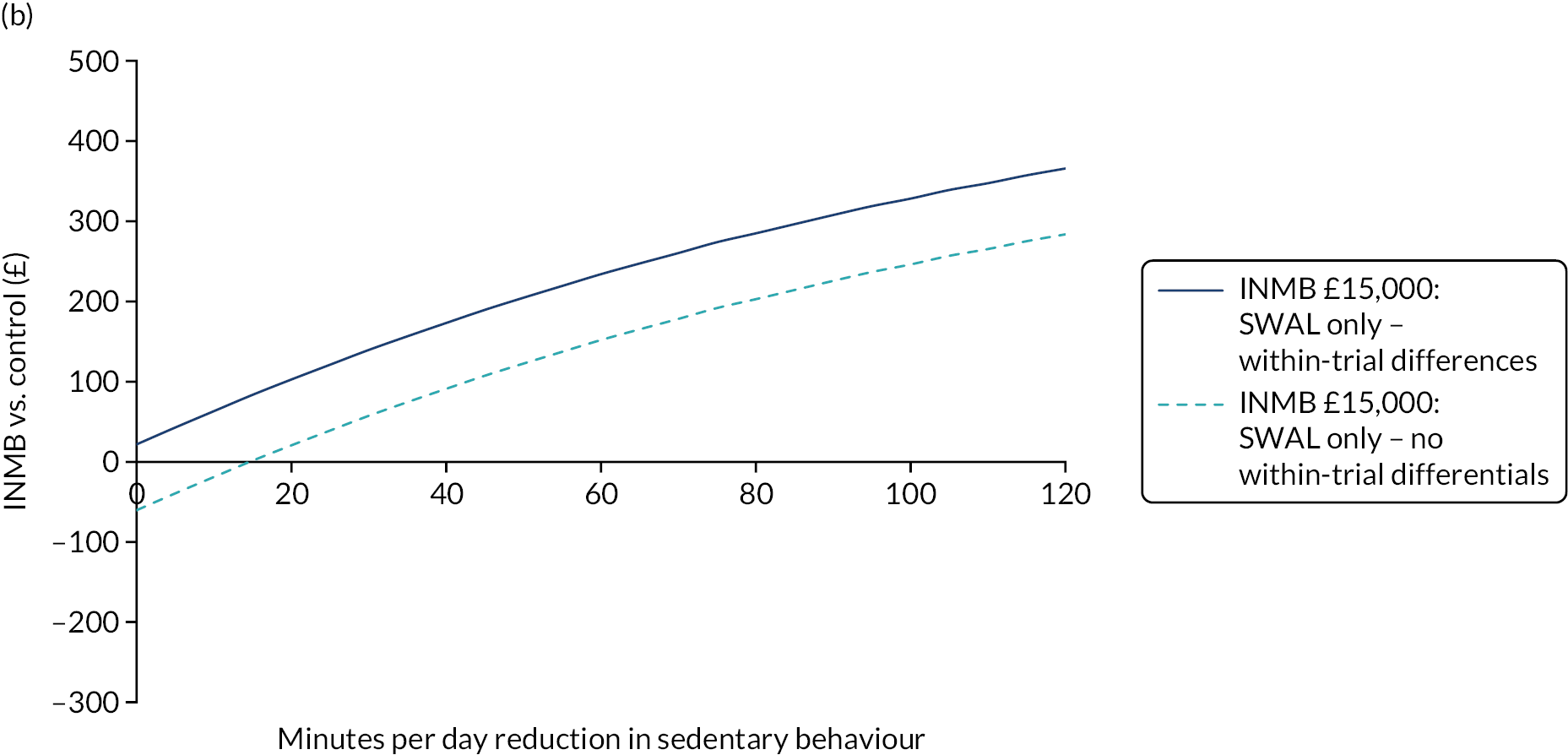

Intention-to-treat analysis